The NTEU has a new report out today forecasting some alarmingly long HELP debt repayment times, including over 40 years in some high student contribution courses. While I agree that this issue needs attention – and have proposed linking student contributions with expected repayment times to narrow the course-linked differences between them – I think the NTEU forecasts are much longer than will typically happen in practice.

The key problem is how the NTEU models expected graduate income. In their report they take starting salaries and then increase them each year by average wage growth over the last decade, 2.3 per cent on their figures.

However graduate incomes usually increase by much more than that. Indeed, the financial value of a degree is opportunities for continuing income growth when the wages of people without degrees tend to plateau after a decade or so in the labour force.

Graduate career wages

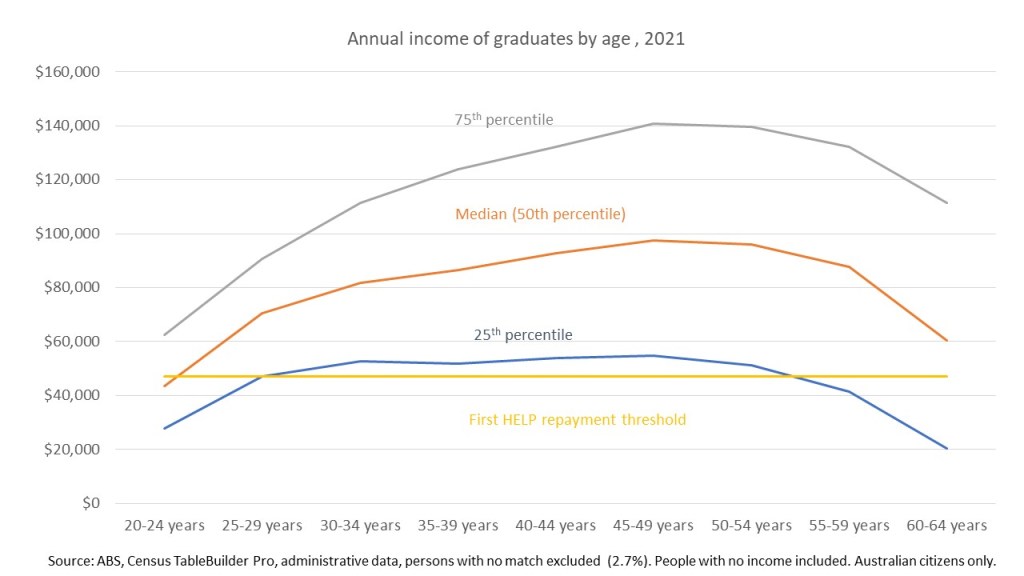

Recently the ABS added ATO and DSS derived income data to the Census dataset, allowing more detailed analysis of income than was previously possible. As the chart below shows for graduates at the median and 75th percentile income does not peak until age 45-49 years, after doubling between the early 20s and late 30s.

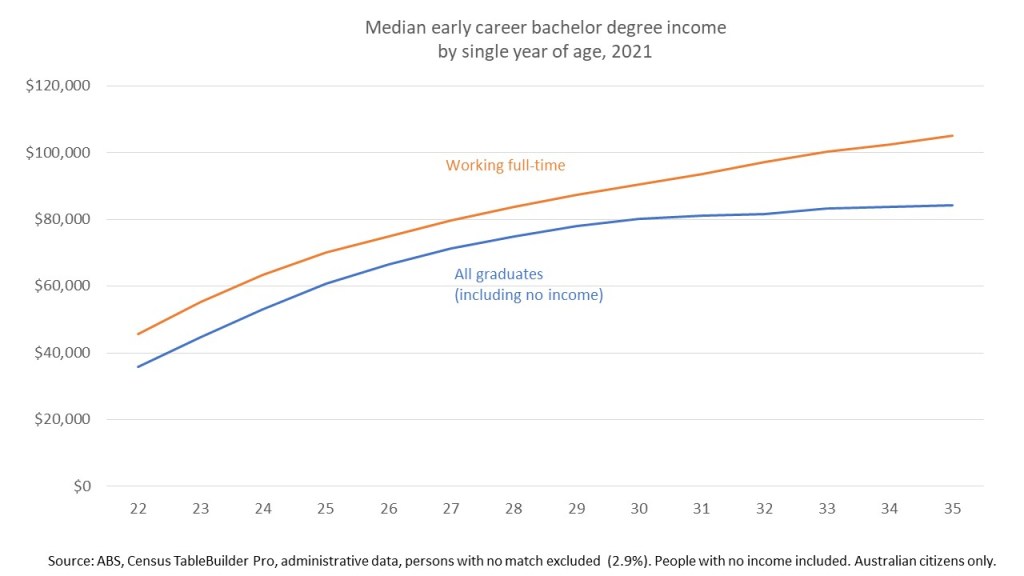

The next chart looks at median income by single year of age in the early career period when most HELP debt is repaid. Initial income levels look affected by people in jobs that don’t require degrees, but as professional careers start and graduates are promoted or switch to better jobs income increases rapidly.

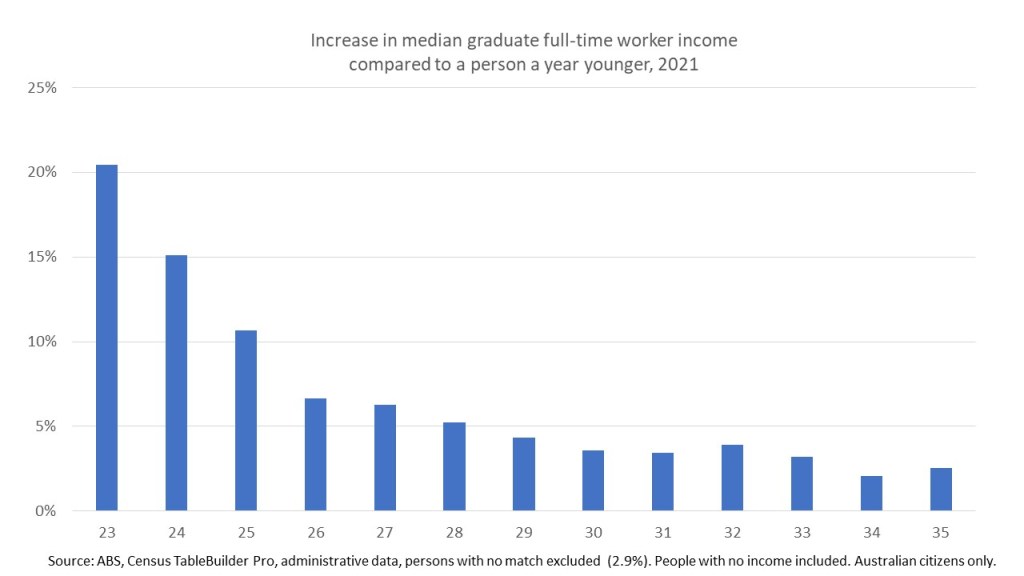

For people working full-time the increase in median income for each additional year of age exceeds the NTEU’s 2.3 per cent in every year between ages 22 and 35 except 33 to 34 years.

HELP debt and repayment

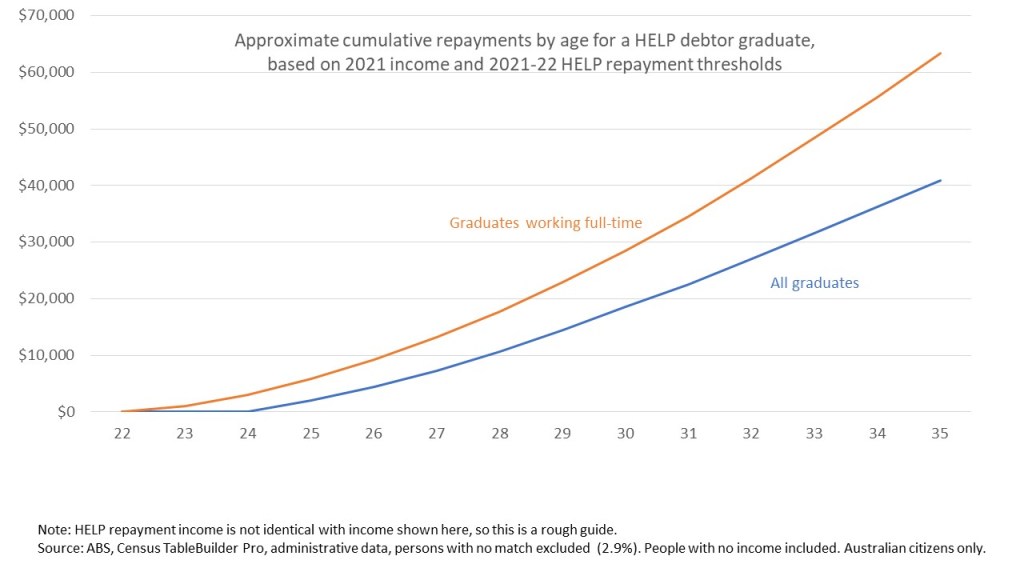

The income recorded here is not the same as HELP repayment income but is much closer than the NTEU figures. These much faster than modelled income increases have major effects on repayment periods. Graduates earn more and move into higher repayment rates more quickly than the NTEU model predicts. Higher annual repayments in early career mean less debt each year to be indexed, limiting another factor pushing up repayment amounts and periods in the NTEU model.

A weakness of both the NTEU approach and mine is that they assume linear careers. In practice incomes vary, especially for women with children. Time out of the labour force or working part-time lengthens repayment times. Each analysis assumes no voluntary repayments, which shorten repayment times.

The chart below is therefore approximate in its cumulative repayment estimates for graduates on a median income. A graduate who completed their degree in their early 20s and consistently earned around the full-time median income should clear HECS-HELP debt associated with any undergraduate course by their mid-30s. The all graduates figure, which includes people with no income or low income (capturing some childcare effects) would clear debt associated with lower-cost degrees like teaching or nursing but not arts, business, or law.

Improving on repayment estimates

The Department of Education already has a dataset which links up enrolment and tax data. It removes non-HELP debtors from the analysis and can incorporate the effects of fluctuating income. It should be used to produce course-based repayment estimates for people currently taking out debt.

Even if the results of this analysis are never used to set student contributions, as I have proposed, it would be useful consumer information. My last year of doing media on indexation issues has highlighted that many people have taken on debts without understanding the implications of doing so. HELP was supposed to reduce price sensitivity and in this it has, for some people, been too successful.