University of Melbourne VC Duncan Maskell secured some not always entirely positive media coverage today for his call to make university education free for domestic students.

University education is free or very cheap for students in some European countries and was also free in Australia between 1974 and 1988.

Why do countries differ on university fees?

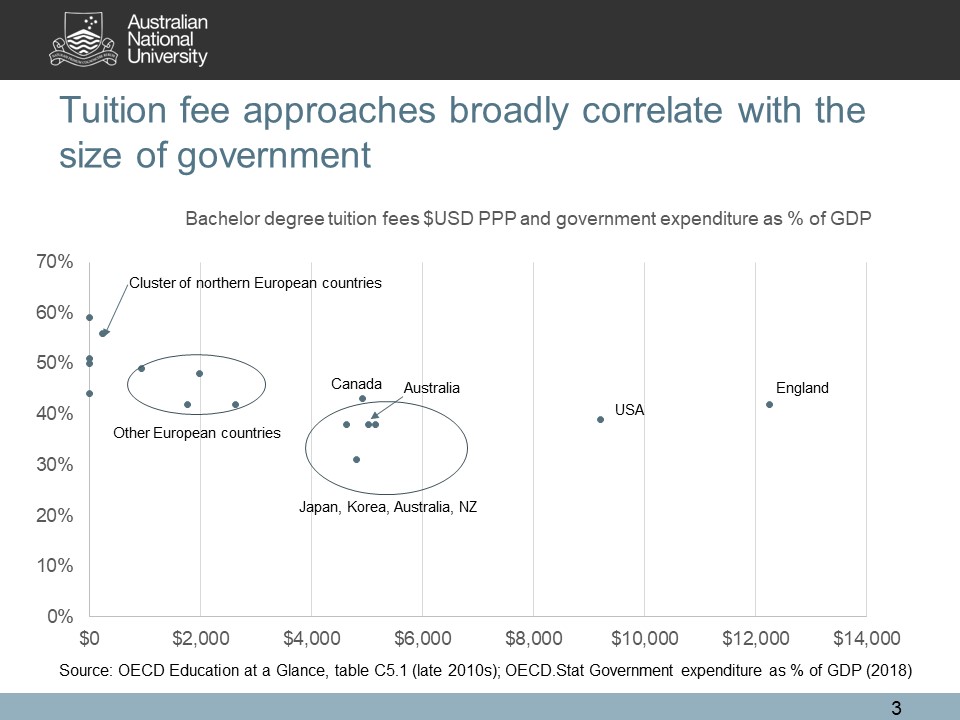

My theory of why countries differ on this issue draws loosely on the work of Julian Garritzmann. We observe broad coherence between higher education finance systems in each country and their overall tax and social service/benefits systems. The chart below shows patterns in the OECD. Australia is in a cluster of countries in our region with government expenditure below 40 per cent of GDP and quite similar fees in $USD purchasing power parity terms. The countries with free higher education tend to have governments that consume more than 50 per cent of GDP.

There is a fiscal and political logic to these patterns. Greater funding of services by the state obviously leads to government expenditure being higher as a percentage of GDP, which requires a larger tax base, which in turn limits the capacity of citizens to purchase these services directly. This creates a political constituency that resists direct consumer fees.

In countries where services are privately funded, or funded in a hybrid public-private manner, the dynamic is more complicated. As in fully publicly funded systems there are constant calls from each subsidised service sector and their beneficiaries for more government funding, but also greater resistance to the tax increases necessary to do this. Taxpayers want to preserve their capacity to purchase services directly, and in means-tested systems like Australia’s the people who pay the most tax often receive no or reduced benefits.

For various historical and political reasons sector-specific exceptions to these general patterns are possible, but short of a broad change to a different type of welfare state these exceptions will appear anomalous and may not be politically stable.

Free education was not stable in Australia because one of the two major parties – the Liberals who are most in favour of moderating taxation – did not support it, and it also had opponents on ‘middle class welfare’ grounds within the Labor Party that had introduced it (and also abolished it in 1989). Germany had modest fees for a while but in their system these were anomalous and did not last. I am not sure whether England will go back to completely free higher education in its current dire fiscal state, but their very high fees look anomalous and the Labour party will do something about them when it returns to office.

Do fee systems affect higher education participation and attainment?

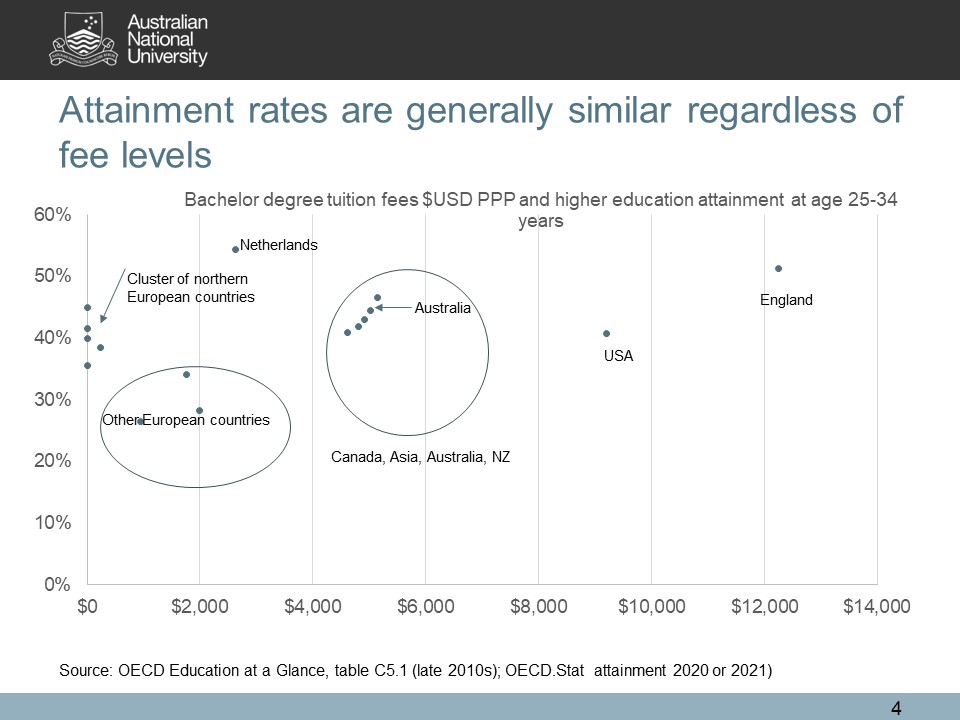

Counter-intuitively higher education funding systems appear to have only small effects on overall higher education participation or attainment rates. While some moderate fee European countries have lower attainment rates by age 25 to 34 years, most other countries have 40-something per cent attainment, with a couple exceeding 50 per cent.

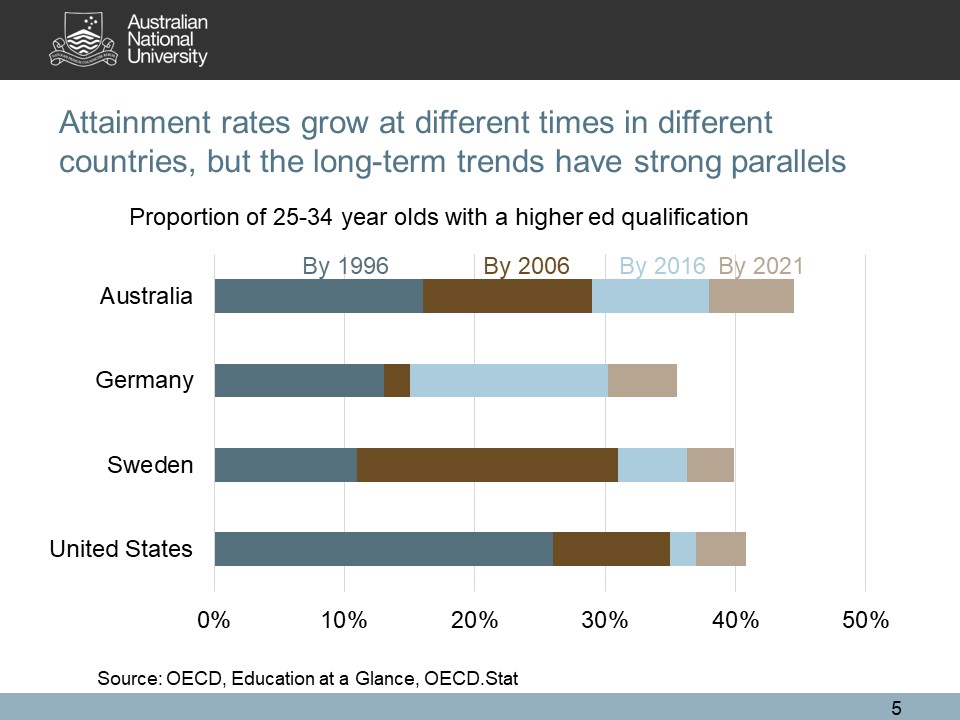

While absolute levels of attainment differ a little between countries, the long-term trends have strong parallels, as seen in the chart below. Funding systems are not the only drivers; there are other issues including school systems (streaming in Germany steers students to vocational education) and country-specific labour markets, which affect the need for higher education qualifications.

But at least in coherent systems ways are found to ensure similar results. In countries with fees, policies such as government or government-backed loans, and private initiatives such as family support and philanthropy, mean that the overall patterns and trends are similar. Countries with fees can to some extent bypass the fiscal constraints of dominant government funders, one reason why attainment is on average slightly higher on the $USD PPP $4,000+ countries (44.6 per cent) in the chart above than in the free countries (40.5 per cent).

Prospects for free higher education in Australia

Many supporters of free higher education in Australia hold personally coherent views. They want the Australian state to be much bigger in general, with higher taxes and more government funded services including higher education. But an ad hoc move to free higher education would be unstable and risky, for reasons I will explore further in a subsequent post.

Thanx for this excellent analysis.

Also, if one were to increase substantially Australian government spending on higher education, surely a much higher priority would be much higher student income support and much less mean means tests.

LikeLike

Interestingly, even international students (UG and PG) do not pay tuition fees in Germany.

LikeLike