The argument that free higher education would create additional higher education opportunities is empirically weak. History and international comparisons show that participation rates increase without it, and indeed due to budget constraints free higher education can lead to lower participation rates.

However there is another argument for free higher education which, while still contentious, has goals and likely outcomes that are consistent with each other.

Free higher education and income/consumption smoothing

The strongest argument for free (or cheaper) higher education is a better balancing of income and consumption over the life cycle. Needs are more consistent through life than income. Most people consume more than they earn when young and old and a large proportion earn more than they consume during their full-time working years. Smoothing these out is one of the principal functions of welfare states.

Compared to upfront fees or mortgage style student loans paid in instalments the HELP repayment system already has strong smoothing effects. It pushes the expense of higher education away from the years when full-time study limits scope for paid work. On low incomes no HELP repayment is required or repayments that are less than the minimum likely mortgage style loan repayment amount. On high incomes HELP repayments are more than the likely mortgage style loan repayment amount.

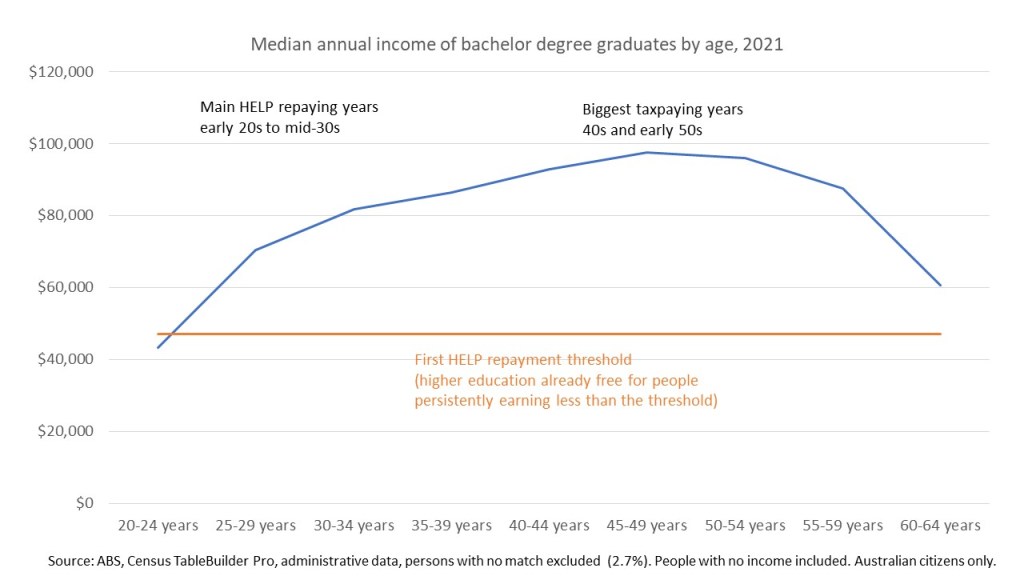

And higher education is already free for HELP debtors who persistently earn less than the first repayment threshold.

But compared to a free education system HELP brings forward the time when graduates ‘pay’ for their higher education. Around 70 per cent of compulsory HELP repayments were made by people aged between 18 and 34 years in 2020-21, before the peak earnings years for graduates as shown in the chart below. Under a free system I assume that graduates in their 40s and 50s would incur the main incidence of indirectly paying for their higher education, when they are in their peak ‘net taxpayer’ phase of their life cycle, financing the welfare state over-and-above the value of services they currently use.

The counter-factuals are complex here, as under the society-wide changes favoured by many free-education advocates taxes are likely to go up across the mid-to-high income range. The increase in disposable income would be less than the savings from not repaying student debt. This system could be more costly than student debt for high income earners (HELP repayments are capped by past borrowing plus indexation, tax is not). But HELP repayments put extra financial pressure on the early adult years when people start families and buy homes.

Other changes have also put added pressure on young adults. Compulsory superannuation, introduced shortly after HECS, makes early career graduates pay for their retirement while they are still paying for their higher education. High property prices mean more intense savings requirements for a deposit as well as putting home buyers into longer repayments periods.

Modifying student contributions and HELP with repayments in mind

While I do not favour free higher education the HELP repayment phase is an increasing concern/interest. It is one reason I support using estimated repayment times to guide student contribution setting. Even if reducing average student contributions is not fiscally feasible it is possible to allocate debt between students in ways that support faster repayment. As this would also reduce HELP bad debt and interest subsidies it would contribute to rather than detract from meeting fiscal goals.

Proposals have been made to raise the first HELP repayment threshold and make the repayment a percentage of income above it, rather than all income as now. This would help manage cash flow for lower income earners. Average repayment times would, however, increase due to more years of zero or low repayments. As the last year of HELP indexation issues highlights, there are benefits in clearing debt as quickly as possible. APRA should retract its misconceived advice on taking HELP debt into account in mortgage lending, but while this is in place it is another reason for clearing HELP debt quickly. I don’t yet have a firm view on the best trade-offs between these competing policy priorities.

Conclusion

The fiscal strain produced by stronger smoothing of income and consumption with free or much cheaper higher education would probably reduce higher education participation rates compared to some version of the current system. This is not inconsistent with the goal of increasing the living standards of young graduates – it would reduce competition in graduate labour markets. It is however in tension with the goal of making higher education opportunities as widely available as possible.

Three excellent and informative posts on free uni and HELP schema.

Do you have a view on a policy where graduates’ have a right to choose whether or not to direct their employer paid superannuation towards their HELP debt, and if so, under what limitations/circumstance?

LikeLike

This has been suggested a few times before, I wrote about it in 2016: https://andrewnorton.net.au/2016/04/13/should-people-use-their-superannuation-to-pay-off-help-debt/

As that post suggests a key issue is the tax treatment of the payment.

There are also political issues about why this exemption to the uses of super money should be made, and not the others that are suggested, especially for home purchase.

LikeLike