A couple of days ago the Sydney Morning Herald published an article on falling enrolments in university humanities subjects, with a focus on history and English.

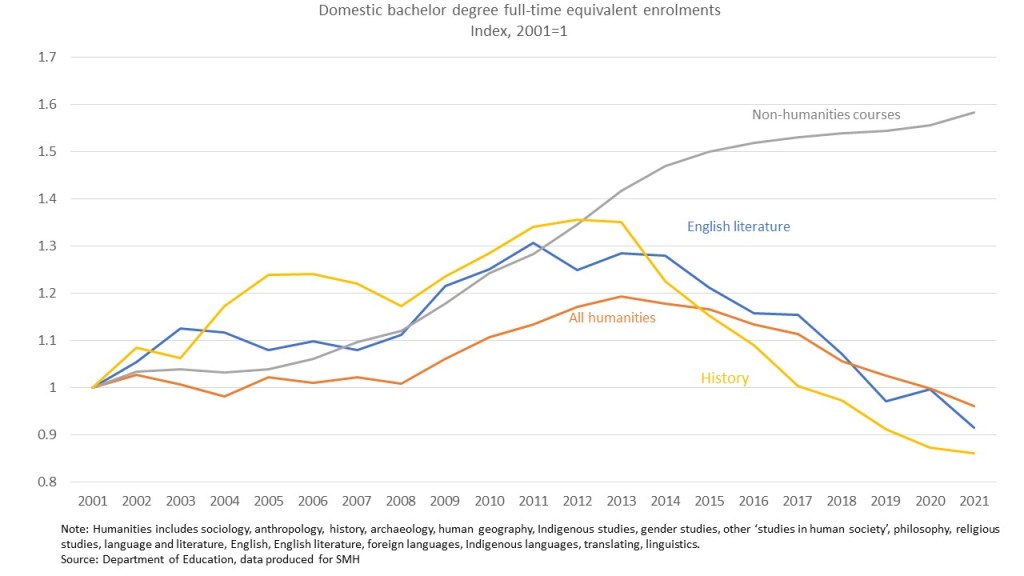

I’ve converted the data into an index to make it easier to see the trends in fields with different absolute numbers of full-time equivalent enrolments. In the late 2000s and early 2010s the humanities shared in general enrolment growth, but after that went into decline. History’s growth and decline were greater than the humanities in general.

Any theories about why the humanities enrolments declined are speculative. We rarely ask prospective or actual students how they choose between post-school options. But there are theories, which I am quoted on in the article. The theories are not mutually exclusive and so combined effects are possible.

Short attention spans?

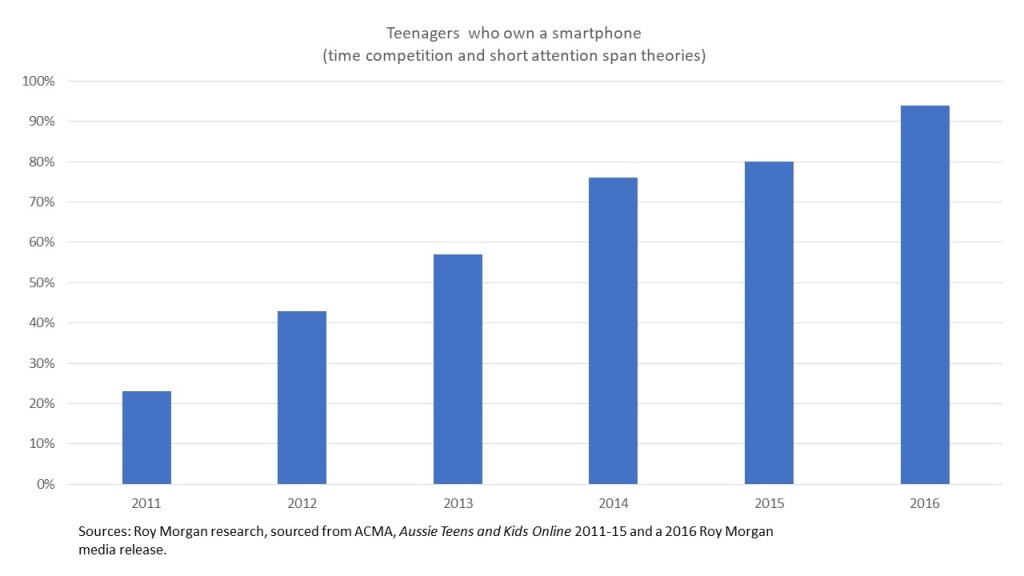

English literature and history both involve time-consuming reading, which counts against them in the smart phone and social media era. I know correlation is not causation, but increasing teenage use of smart phones matches with the early 2010s humanities decline.

Employment prospects

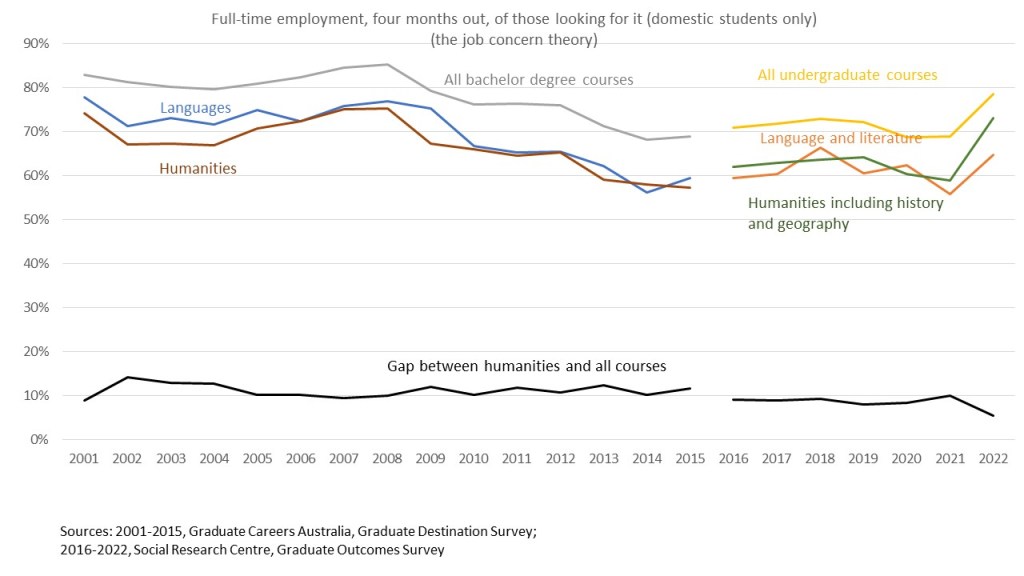

Full-time employment prospects for recent bachelor degree graduates start declining in 2009 after the GFC damaged economic confidence and reached their nadir in 2014. Humanities outcomes are persistently about 10 per centage points worse than the all bachelor degrees figure.

The timing isn’t perfect here as enrolments keep growing until 2011 for English literature and 2013 for history and the humanities in general despite deteriorating employment outcomes. But overall enrolments are growing strongly in this period as the demand driven system is phased in. Humanities are slowly losing bachelor degree full-time equivalent enrolment share (10.1 per cent 2009, 9.5 per cent 2013) while their absolute number of enrolments increases.

The relationship between employment and enrolments is complex. In the aggregate, higher education enrolments tend to be counter-cyclical. When work is hard to find some people study to improve their job prospects; when jobs are plentiful enrolments go down. Within the group of people who do apply and enrol we have regularly seen apparent specific course responses to occupation and industry-level labour market trends in applications and enrolments. These can run against the general trend.

Courses like arts have a less predictable relationship with the labour market than degrees aimed at specific jobs. Arts students are more likely to choose their course based on interests alone rather than being concerned about labour market outcomes. And because arts graduates end up in many jobs the specific information about occupations and industries that influences choices in the more vocational fields is less available.

Perhaps as a result the information that drives any arts employment-enrolment nexus is less timely. Possibly persistent negative publicity around the annual graduate employment survey results and anecdotal evidence through social networks eventually influences course choices. However enrolments kept going down after arts employment outcomes stabilised.

Job-ready Graduates

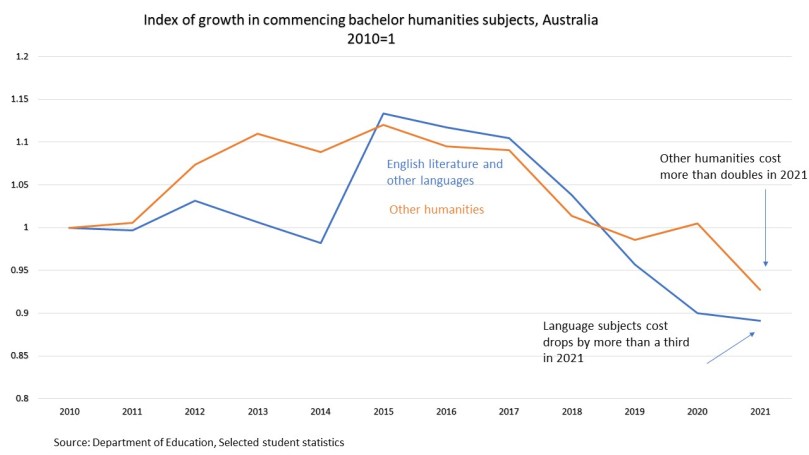

Obviously the fee changes in Job-ready Graduates did not trigger a trend that started years before they were announced. But could they have exacerbated it? Here I am switching to commencing student EFTSL, which I only have at a higher level of aggregation than the SMH data. My time series is shorter, starting in 2010, part way though the growth phase.

Eccentric Job-ready Graduates pricing decisions create opportunities for comparative analysis. As the chart above shows language-related subjects and other humanities do as poorly as each other for job readiness. Yet language subjects were incentivised with discounted student contributions while other humanities were disincentivised by more than doubling student contributions.

As the chart below shows other humanities commencing enrolments fell sharply between 2020 and 2021 after a slight recovery between 2019 and 2020. Discounting language subjects did not reverse their long term decline but the 2020 to 2021 drop was small, falling only 120 EFTSL to 3,977.

This is consistent with predictions I made during the Job-ready Graduates debate. Somebody committed to a career choice is not rationally going to be deterred by higher student contributions. While they would rather pay less for their higher education, they are not going to change their whole life plan to shorten their HELP repayment phase by a few years. But someone studying arts principally out of interest may decide that $15,000 a year is too much.

Another group of prospective students who could be influenced are those who say they are just ‘marking time’ while they decide what to do. $15,000 a year is an expensive way to make a decision, which could be done more economically by getting a job instead.

Conclusion

I’d be very surprised if the Universities Accord process did not put arts back in a lower student contribution band. And I am now confident that the 2023 graduate outcome survey will show a strong continuation of the 2022 employment improvement shown above, although with the doubts mentioned about whether/how this information will reach prospective students. But two of the the three potential causes of declining humanities enrolments discussed in this post should move in a more favourable direction in the near future.

Thanks for this thorough evidence based analysis. Now for an ‘ancedata’ response. I teach into a media and communication degree and have noticed a marked increase in students discussing price of courses/degrees in the last 12 months and questioning if they can afford post-grad/MA study. I’ve also had a bright 15 year-old interested in a general arts degree telling me that they can’t do it as it will cost them $100k. I asked where they got this info and they suggested it came from general news and their teachers. I explained it was incorrect and that arts graduates do find meaningful well paid work, especially over a lifetime. This limited example serves to illustrate the misinformation about cost and ‘usefulness’ of arts degrees within public (and private) discourse and I wonder at what cost to an educated and open civil democracy?

LikeLike

Thanks very much for this interesting article Andrew. Another great contribution to the riches of your site.

Coincidentally, last week I posted a piece about a similar trend in the humanities in ew Zealand universities. See this link https://rogersmyth.com/what-is-really-happening-to-the-humanities-in-nz-universities/.

My article traced trends in enrolments and degree completions in the humanities over the last decade or so but also reached back into the 1970s and 1950s, an era when the humanities were seen as strong. I also looked at post-study destinations and earnings of humanities graduates. This raised two other issues – how students choose majors and the matter of the usual arguments made for the continuing relevance of the humanities (namely generic skills). On subject choice, I reviewed some of the literature, much of it Australian (including a couple of pieces of HE commentary from Carlton).

I also traversed some of the trends in Canada and the UK.

Thanks again for another excellent piece – keep up the good work.

Roger Smyth

LikeLike

Thanks Roger. I’d seek the UK reports but interesting that trends are very similar across the English speaking countries.

LikeLike

Thanks Andrew: most helpful albeit dispiriting, especially when it seems JRG is with us until at least 2027.

LikeLike