While I agree with the goals of today’s big migration policy changes, they will make life more difficult for universities relying on migration-motivated international students. In most cases, former international students will be able to stay in Australia on temporary graduate visas for less time than now. Other options for remaining in Australia, such as returning to a student visa, will become more difficult.

These policy changes aim to reduce temporary migrant numbers. The pressure temporary migrants place on accommodation and other services made this an urgent policy and political issue. But prior to this there were also significant concerns about temporary migrants themselves, in their vulnerability to labour market exploitation and prolonging their time in Australia in the often false hope of eventual permanent residence, as ‘permanently temporary’ migrants. The Parkinson migration review, released in March this year, set out an agenda for change.

Future policy on permanent residence is still under development, with some signals discussed below. Whether the number of former international students getting PR will go down remains to be seen. But clearer rules will mean PR aspirants can cut their losses at an earlier point. Fewer will delay important career and family events and decisions due to uncertainty about their long-term country of residence.

Shorter-stay temporary graduate visas

In September 2022 the government announced its decision to add two years to the sub-class 485 temporary graduate visa for graduates with degrees in areas of ‘verified skill shortages’. In the critique I wrote at the time I was ‘far from convinced that a 485 time extension is a good or ethical policy’, and so I am glad that this policy will be abolished.

As the chart below from the migration plan shows, they will also cut the base time period for a masters by coursework from three years to two years, and for a PhD from four years to three years. The regional extension, however, will remain.

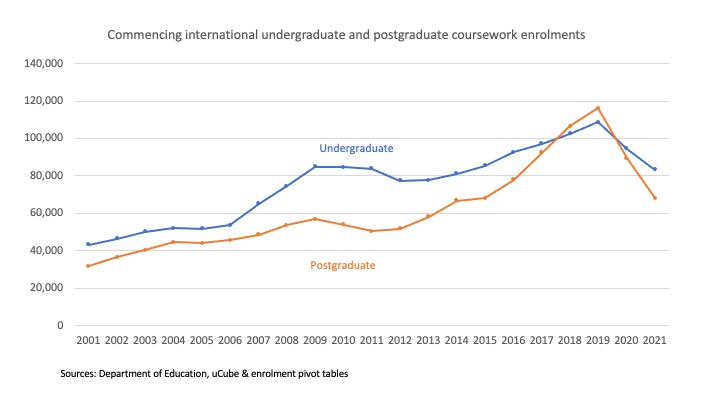

The impact is biggest for masters by coursework students in courses listed as eligible for the two-year extension, who have been moved from a five-year 485 visa to a two-year visa. The bachelor/masters 485 visa length differential probably contributed to the changing balance between undergraduate and postgraduate commencing enrolments, as seen in the chart below (the current 485 visa system starts in 2013).

According to the government’s timeline, implementation of this policy will commence in mid-2024, so some graduates may be able to take advantage of the old policy in the interim.

[Update 17/12/23: Due to the Australia-India Free Trade Agreement, exceptions will apply for Indian graduates. For them, a masters by coursework 485 visa will remain at three years and a PhD at four years. Indian students with first-class honours bachelor degrees in STEM fields can get a three year 485 visa. In 2022-23, 35 per cent of 485 visas granted went to Indian nationals.]

Age and language requirements

The maximum age for applying for a 485 temporary graduate visa will decline from 50 years to 35 years. The reason given is to better align the 485 visa with the maximum age for a PR visa, which is 45 years.

In 2016, unfortunately the latest year for which I can get reasonably good student and 485 visa age data, 4.5 per cent of their combined population was aged 35 or more. [Update: Ly Tran observes that this age cut-off will create significant problems for research students. In 2022-23 20 per cent of research students were 35 or over at the time of their research visa grant, and another 29 per cent were aged 30-34 years, suggesting many will be over 35 by the time they finish.]

The English language requirements for a 485 visa will go from an IELTS 6 to 6.5. The minimum IELTS for a student visa will go from 5.5 to 6.0. In research my team at Grattan did in 2018, universities had minimum IELTS of 6 or 6.5, so the initial student visa change should not cause too many problems but the 485 rule might.

English language skills are a perennial international student issue. The government will also ‘strengthen education provider requirements to report students’ English language proficiency at enrolment.’

On the upside, there will be a 21-day service standard on the renamed ‘post higher education work stream’ 485 visa, so that applicants who tick all these boxes will get their visas more quickly. The current Home Affairs visa processing guide suggests that for applications put in last week half would be processed within 44 days.

Harder paths back to student visas

The genuine temporary entrant requirement for student visas – which absurdly required applicants to say they do not intend to stay in Australia permanently while other visa programs gave them incentives to do so – will be abolished in favour of a genuine student visa.

One of the tests for the genuine student visa will be the ‘usefulness of the intended study to their future career prospects’. I expect that will be fairly easy to game for the first student visa, but harder to prove when trying to move to another student visa with no connection to the originally-nominated occupation.

In 2022-23, to give examples of visa changes likely to be viewed with suspicion, 14,207 people went from a higher education student visa to a VET student visa, and 10,102 people went from a 485 visa back to a student visa.

Other temporary visas with work rights

The government will create a new four-year Skills in Demand visa which, if I understand it correctly, requires employer sponsorship but does not require the employee to remain with that employer. Employers would need to be ‘approved’ and appear on a public register. These periods of employment would provide points for points-tested visas.

The most common Skills in Demand visa will be a ‘Core Pathway’. To be eligible for this pathway, graduates (it’s not just for graduates, but sticking to my higher education subject) will need to have an occupation on a list determined by Jobs and Skills Australia. Registered nurses and secondary school science teachers are mentioned as examples. Jobs will need to pay at least $70,000 a year (indexed).

A Specialist Skills Pathway will not be tied to specific occupations. According to the government this visa pathway will ‘help meet labour needs that exist at an individual firm level and assist companies in acquiring specialist knowledge, niche technologies or research expertise unavailable in Australia, and skillsets not picked up in occupational definitions.’ This visa pathway has a minimum salary of $135,000 a year.

If international graduates can get jobs that qualify for a Skills in Demand visa this could be more attractive than the reformed 485 visa. The risk, however, is that if the employee loses or leaves their job they have 180 days to find another employer. If they don’t their visa will expire. The 485 visa is not conditional on employment.

Former students use the existing subclass 482 temporary skill shortage visa. In 2022-23, 4,104 went to a 482 visa from a temporary graduate visa, and 5,882 from a student visa.

Employer understanding of the visa prospects of former international students will be critical to their employment opportunities. If employers think they can fairly easily keep a graduate beyond the two-year 485 visa, such as by using a Skills in Demand visa, that will make the international graduate as or more attractive than now – six years of employment for a coursework graduate (two on the 485, four on Skills in Demand), compared to four years for a bachelor graduate on a 485 and five years for a masters graduate.

Changes to points-tested visas

On the crucial issue of new points-tested visas we must wait for another government discussion paper. That will be informed by research from the ANU’s Tax and Transfer Policy Institute on the factors that drive migrant success. Their website is down at the time of writing, but last time I checked they had offered a seminar on the subject but the paper itself was not available.

It’s clear, however, that actually working in a designated occupation, as opposed to just having a degree related to such an occupation, will be important.

Today’s strategy paper also suggests that spouse skills would be taken into account, along with age and level of English.

Regional study, however, is deemed a ‘poor predictor’ of labour market success. This is potentially significant for regional universities. For the current most common work-related PR visa for former international students, the sub-class 190 skilled nominated visa, regional study points look significant. In the SkillSelect data, 35 per cent of the applicants claiming Australian study points who had made it to the application stage also claimed regional study points (in this system they cannot apply unless they have been invited to do so, after putting in an expression of interest).

A critical issue will be whether points for Australian study remain and if so at what level.

Conclusion

Today’s announcements are not good news for universities, although they can be glad that ideas like capping international student numbers or increasing visa application fees did not appear.

However the balance between education sector self-interest and the interests of both international students themselves and the broader Australian community had been lost – some people would say long ago, but especially over the last year of wild growth in student and former student numbers coinciding with a general accommodation crisis.

The policy re-set announced today will help restore that balance.