The Universities Accord final report proposes changing how HELP repayments are calculated. It recommends abolishing our current system, which levies a % of all income once an income threshold is reached. It would be replaced with a system that charges a % of income above the threshold – a marginal rate system.

A major reason given for this change was to end the ‘unfair situation’ of some HELP debtors having very high effective marginal tax rates. These can exceed 100% in some cases, so that an increase in taxable income results in lower disposable income. In addition to the fairness issues, high EMTRs can lead to people working fewer hours and less income tax revenue.

Other Accord final report comments, however, suggest HELP repayment redesign with purposes beyond the EMTR issue. While not specifying thresholds or marginal rates, the report suggests a system in which the ‘majority of HELP debtors who make a repayment … would repay less in a given year’. They warn, however, that a ‘small number of higher income debtors (likely less than 10% of HELP debtors) [would] make higher repayments in a given year’.

Subsequent Jason Clare media interviews suggest that policy thinking on repayment systems has moved beyond a general preference for a marginal rate system. Referencing unpublished research by Bruce Chapman, Clare said on the day the final report was released that ‘someone on an income of $75,000 a year would pay every year about $1,000 less.’ He gave the same example again this week.

Speaking to the SMH, Chapman expanded on how the new system might work. He envisaged a multi-rate marginal HELP repayment system: ‘a person earning $86,000 would only be taxed the 5 per cent repayment rate on the income above the threshold at which the rate kicks in, being $84,430. All income below that threshold would be levied at the lower rates.’ A multi-rate marginal system is also consistent with the Accord final report reference to some HELP debtors repaying more each year than they do now.

What marginal rate does repaying $1,000 less on $75K imply?

I thought I could reverse engineer the marginal rate implied by reducing repayments by $1,000 for someone on $75K. But I need to know what year the minister was referring to. It could be this financial year – Chapman’s example of $84,430 is the 5% of all income threshold for 2023-24. In 2023-24 a $1,000 repayment reduction implies a marginal rate of 6.9% (chart below), assuming the current first threshold. However higher education analysis often uses out-of-date data. The Accord final report sections on marginal rates include examples from 2019-20 and 2022-23. For 2022-23 the implied marginal rate was 8.9%, up from 8.5% the year before.

That I can get the different figures shown in the chart highlights the idiosyncrasies of the current system. CPI indexation of 18 thresholds can cause a person’s effective marginal HELP repayment rate to bounce around from year to year, changing the work incentives each 1 July.

What would a 7% single marginal rate do to total HELP repayments?

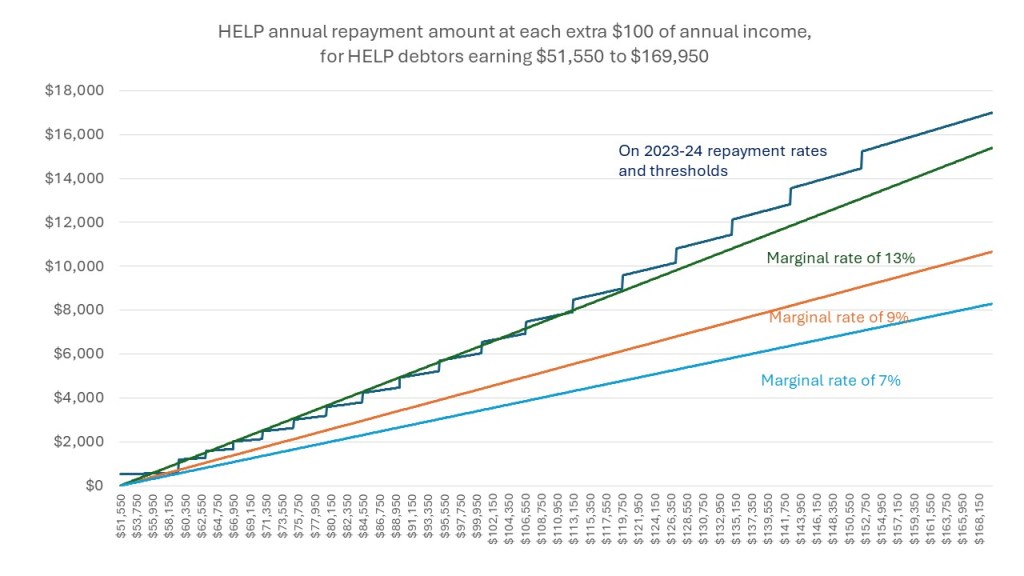

I’ll assume that the Chapman analysis /Clare claim was based on 2023-24 data and round it up to 7%. If a single marginal rate, for 2023-24 7% on the margin above the first threshold of $51,550 would lead to lower annual repayment amounts across all income levels, not just the lower income groups suggested by the Accord final report (chart below).

Data on how HELP debtors are distributed across HELP repayment categories released last year supports a rough calculation of repayment amounts based on a 7% marginal rate for all. My simple and approximate repayment model estimates a repayment revenue drop of $2.2 billion, or 47% on the $4.77 billion it estimates would be collected on current settings.* This would not be acceptable to the government.

A 9% marginal rate, which is used for the English student loan repayment system, would of course improve these numbers, but would still reduce HELP repayment revenue by 31%, or $1.49 billion less than the current system. This has a near-zero chance of being endorsed by the government.

A marginal rate of 13% would bring in similar total repayment revenue as the current system. On my imprecise model, it would collect $39 million, or 0.8%, less than the current system. Given the limits of my calculations the current % of income system and a 13% single marginal rate system look financially equivalent from a government cash flow perspective. Mark Warburton, who has been calling for a marginal rate system for some time, previously estimated that a 13%-15% rate was needed.

A 13% marginal rate would not meet Accord criteria

A 13% marginal rate would help debtors with high EMTRs just above a threshold. But as the chart above shows it would lead to many other low-to-middle income HELP debtors paying more than under the current system, while high income debtors pay less than now. This is not what the Accord panel wanted and may explain the political origins of the multi-rate marginal system idea.

A multi-rate marginal system that could reduce repayments for lower-income HELP debtors

There are numerous possible permutations of a multi-rate marginal repayment system, and with my limited data and resources I have only tried a few.

I started by giving the minister his $1,000 repayment reduction on an income of $75,000 for 2023-24. On the calculations above, that means a marginal rate at 7% from the current first threshold of $51,550 up to the current income repayment category that finishes at $75,140.

The trouble with a low starting point under a multi-rate marginal rate system is that all repaying debtors, and not just those with incomes under $75,140, would repay 7% of their income between the first threshold of $51,550 and $75,140.

In this first threshold level every 1 percentage point on the marginal rate makes a significant difference to total repayment revenue. This is because it applies to all HELP repayment income in this repayment band. In the 2021-22 data I am using, all 1.1 million repaying HELP debtors would repay 7% of their income in this range, not just the half million whose incomes are $75,140 or below.

By contrast, at the upper end of the HELP repayment income distribution each additional 1 percentage point makes much less of a difference to total HELP repayment. The rate is only applied to the income above the previous marginal rate maximum threshold, not to all income as under the current system. With relatively low numbers of debtors in the upper income brackets the marginal revenue is multiplied by many fewer people than in the lower income brackets. These two drags on total revenue raised create pressure to push marginal rates up higher and higher to get meaningful revenue and/or to impose the higher rates at lower income levels.

Recovering revenue with higher marginal rates

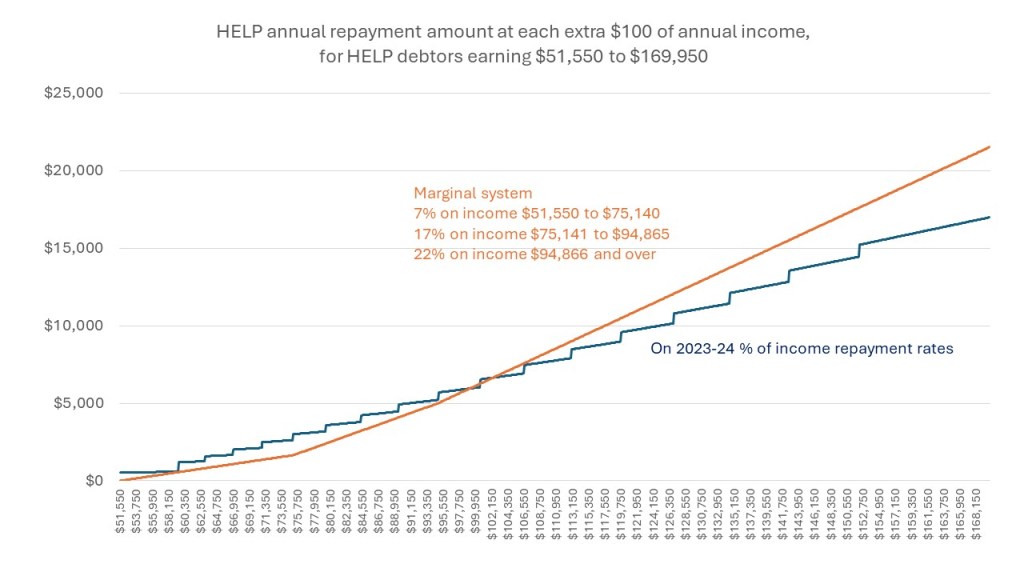

The model below is designed to maintain roughly the same total repayment revenue as the current system while preserving the 7% repayment rate on a HELP debtor earning $75K. It is a 7-17-22 model: 7% between $51,550 and $75,140, 17% between $75,141 and $94,865, and 22% on $94,866 and above. But this option has significant problems.

The need for high marginal rates above the 7% bracket to recover lost revenue takes us back to the EMTR problem we are trying to solve, albeit well below 100% and displaced to different parts of the HELP debtor income distribution.

The revenue assumptions about the upper income levels would apply in year one but weaken after that. This is because increased annual repayments would reduce the time until all remaining debt is cleared. At the upper end of the chart the annual repayments are equivalent to around 90% of the average remaining debt for this group. The number of HELP debtors in the higher income ranges would therefore fall, undermining the revenue assumptions of a static model.

A multi-rate marginal system with lower EMTRs

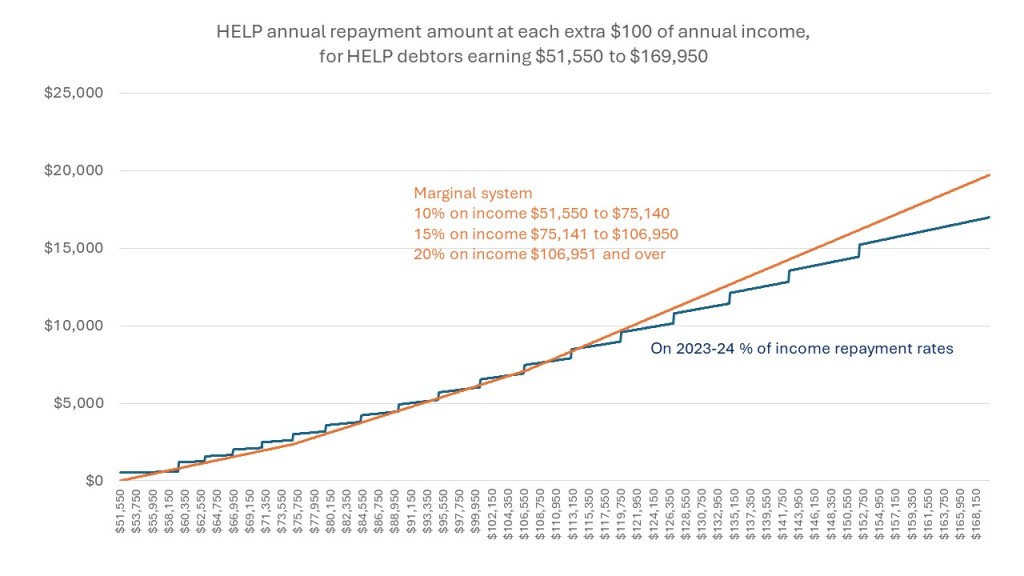

To maintain rough total repayment neutrality but reduce EMTRs a 10-15-20 model would charge a base repayment rate of 10% above $51,550 up to $75,140, 15% from there to $106,950, and 20% on incomes above that.

Compared to the 7-17-22 model, this 10-15-20 model allows a second threshold repayment rate that is two percentage points lower and stays at the second rate for another $12,000 of income. On 2021-22 data that would save about 9% of repaying debtors from moving to the top marginal repayment rate. The top marginal rate is also 2 percentage points lower.

Obviously, however, this model does not cut annual repayments for lower-income debtors as much as a 7% base rate.

As the chart below shows, the 10-15-20 marginal repayment model would deliver modest annual repayment reductions to most, although not all, repaying HELP debtors up to about $114,000 a year. Debtors with incomes near the lower-bound of each current HELP repayment band – those with high EMTRs now – benefit the most. Those with incomes towards the upper-bound of each current HELP repayment band benefit the least and in some cases would repay slightly more each year than now. Debtors earning more than $114,000 would consistently repay more each year than under the current system. This would speed up repayment times for debtors in the 20% band and over time reduce their numbers, but less so than the 7-17-22 model.

On the 2021-22 numbers, 46% of repaying debtors would have a peak marginal rate of 10%, 37% of repaying debtors would have a peak rate of 15%, and the remaining 18% of repaying debtors would have a peak rate of 20%.

Conclusion

Using my assumptions and data I can’t get a marginal rate repayment system that would reduce repayments on some earning $75,000 by $1,000 a year without causing undesirably high marginal rates cutting in at undesirably low thresholds further up the HELP income distribution. My 10% marginal system can however reduce the annual repayments of someone on $75K by about $600.

One key difference between my analysis and the Accord proposal could be that I have tried to maintain roughly equivalent total annual repayments as the current system. The Accord final report mention of higher repayments for upper income earners is a sign that they have tried to at least partly offset revenue losses from lower income earners. But they may still favour significantly reduced total repayments. With vast other new spending recommendations in the Accord final report this is a recipe for rejection.

I’ll stress again that my estimates are crude and restricted to re-using publicly available summary data. Later and more detailed data would produce different results, and could be used to experiment with a wider range of thresholds and rates.

But what I have done illustrates the broad issues. I will discuss the politics of these in a subsequent post.

====================================================================

* 2023-24 HELP repayment rates. HELP repayments were calculated at the mid-point of each 2023-24 HELP repayment income range, except for the top category of income above $160,274, where I used $165,000 to calculate repayments. This probably understates repayment revenue from high income earners in a static model. As noted above, however, their higher annual repayments under multi-rate marginal systems mean that they will complete repayments more quickly than under the current system. This means that my model may over-estimate the longer-run number of people in the top marginal rate category.

For the current system, the repayment calculation is the relevant % of all income at that mid-point. For the single-rate marginal system, it is the relevant experimental % of the mid-range repayment income category minus the 2023-24 first threshold, $51,550. In the later multi-rate marginal system calculations it is this calculation plus a % of income above the second or later threshold.

As an example take a person earning $85,000 a year. Under the current system this person is in the 5% of all income repayment band. The repayment calculation is $85,000 * 0.05 = $4,250. Under a 10% single rate marginal system the calculation would be 10% of the person’s income minus the repayment threshold. In this case $85,000-$51,550=$33,450, 10% of $33,450 = a repayment of $3,345. For a multi-rate marginal rate system say a 15% marginal rate applied from $75,000. The first 10% of the second marginal rate is already covered in the first calculation. To that we need to add 5% to get to the 15% marginal rate. The 5% applies to the the person’s income of $85,000 minus the second threshold of $75,000 = $10,000. 5% of $10,000 = $500. This is then added to the original repayment amount: $3,345 + $500 = total repayment of $3,845.

To calculate total estimated repayments these calculations were multiplied by the number of HELP debtors reported in that range for 2021-22.

The total estimated revenue from my simple model using 2023-24 thresholds and rates but 2021-22 HELP debtor numbers was $4.77 billion. The actual 2021-22 compulsory repayment revenue was $4.78 billion. This suggests that despite the limitations of my simple model it produces results similar enough to recent actual totals to be suitable for the broad comparative purposes of this post.

Thresholds and rates aside, I expect a softening of compulsory repayment revenue in 2023-24 compared to recent years, as a) many debtors will have fallen back into a lower repayment category due to high CPI indexation of the thresholds, including to no repayment; and b) the very large increase in voluntary repayments (up from $780 million to $2.9 billion) and people who finished repayment in 2022-23 (up from 145,403 to 218,462), presumably both to avoid 7.1% indexation. This has brought forward money that would otherwise have been compulsory repayments in 2023-24 and subsequent years. These downward pressures on compulsory repayment levels will to some extent be offset by the continued strength of the graduate labour market.