This morning The Conversation published my argument, made last month on this blog, that HELP debt should be indexed at the lower of CPI or 4%. I argue that this is better than the other suggested ‘lower-of’ options, such as the government bond rate, the RBA cash rate, or a wage increase indicator. The Universities Accord final report chose the last option, specifically the Wage Price Index (WPI). WPI measures changes in hourly rates in the same job.

All the CPI alternatives have a relationship with CPI

A problem with all the lower-of proposals, except a fixed maximum, is that they have a relationship to CPI. If inflation starts going up the RBA increases its cash rate and government bond holders want higher interest rates to protect their real value. Workers and unions, often supported by policymakers, seek inflation compensating wage increases.

For wages set nationally, the federal government wants the minimum wage increase linked to inflation this year. If the Fair Work Commission grants this increase, minimum wage and other CPI-driven wage rises will flow through to future WPI figures.

Real wage increases, over-and-above CPI, also push up WPI. Aged care workers have recently been awarded a large real wage increase. Statistics on enterprise agreements show wage increases returning to their normal pattern of exceeding both WPI and CPI.

Lagging indicators

Although all the suggested variable CPI alternatives for indexation have an association with CPI, typically they are lagging indicators – they start increasing after inflation becomes apparent.

This is especially the case for the WPI. Minimum wage reviews and enterprise agreements usually have fixed schedules. For employees not covered by these systems, employers often have annual salary reviews. These wage-setting mechanisms delay the flow of inflation-compensation wage increases through to the WPI.

If real wage increases are zero or low – an important ‘if’ as real wage increases are reflected in the WPI in most years – wages will be below inflation in the first stage of a high-inflation period. This scenario played out in the early 2020s. Inflation started increasing in 2021, and year-on-year WPI indexation would have been lower than actual CPI indexation in 2022 and 2023.

As the CPI exceeds the Reserve Bank’s target 2% to 3% range, the RBA increases interest rates to reduce inflation. Inflation remains above its target range, but is trending down as lagged wage increases take effect, restoring inflation as the lower of the CPI and WPI.

Lagged CPI indexation undermines the lower-of CPI or WPI policy

The lag between CPI and WPI is the principal protective mechanism for HELP borrowers for this ‘lower of’ indicator. But the odd CPI formula used to index student loans dilutes the lag effect.

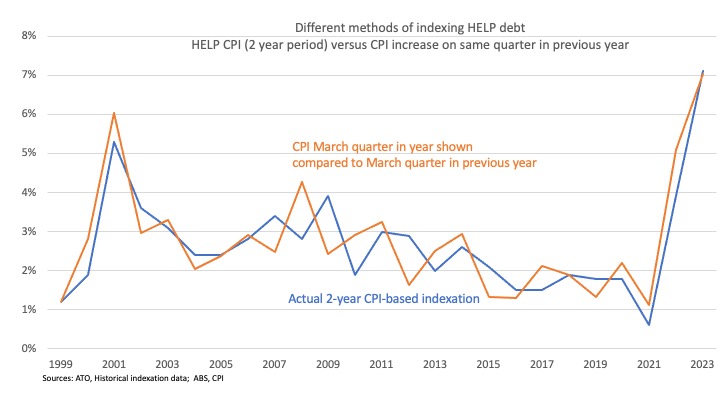

The HELP indexation formula first requires adding up two sets of ABS quarterly CPI index numbers. For 1 June 2024 indexation the two sets will be (June 2022+September 2022+December 2022+March 2023) and (June 2023+September 2023+December 2023+March 2024). Indexation will be the percentage increase between the first and second totals. As the chart below shows, this tends to delay the indexation effect of inflationary spikes, compared to a normal annual inflation calculation method, which in this case would measure the increase in the CPI index numbers between the March quarter in 2023 and the March quarter in 2024.

This formula can also delay the indexation effect of declining inflation, by reducing the impact of relatively good recent quarterly CPI index numbers on the overall calculation. We don’t have the March 2024 quarter indexation number yet, so as an example I applied the same methodology but used the 2022 and 2023 calendar years, finishing with the December 2023 quarter. A simple December quarter 2022 to December quarter 2023 method would produce indexation of 4.1%. But the HELP indexation formula would produce indexation of 5.6%. The expected relatively good March quarter index number should bring actual indexation down below 5.6%, but to a level still above a simple annual % increase method.

The underlying data is the same but with a different time sequence, so over the long run the two systems produce very similar averages. Between 1999 and 2023 average actual indexation has been 2.7%, while the average of a year-on-year CPI indexation system would have been 2.78%, because the recent inflationary surge flowed through more quickly. But the averages will even up after indexation this year.

The current system has a small benefit for existing HELP debtors. Delaying the inflation flow-through reduces compound indexation (i.e. indexation of previous indexation amounts). For example, in 2022 actual indexation was 3.9%, instead of the 5.1% it would have been with March quarter 2021 to March quarter 2022 CPI.

But for a lower-of CPI or WPI policy, using the conventional annual measure of inflation would be more effective in delivering savings to HELP debtors. WPI has been lower than this measure of inflation seven times in the last 25 years, compared to four times using the actual current HELP indexation system.

Conclusion – a simple maximum indexation level is best

Especially with a change to the CPI indexation calculation, the Accord idea for lower-of CPI or WPI indexation can deliver benefits to HELP debtors in some circumstances. But the contingency and complexity of these circumstances reinforces the case for a simple maximum percentage amount. Only a tiny minority of the population knows what the WPI is, how it relates to inflation, or how inflation calculation methods affect whether CPI or WPI will be higher in a given year.

This low understanding, plus some outlier years in the CPI-WPI relationship, has made lower-of CPI or WPI indexation look like a better political solution to the indexation problem than is actually the case. The more than 240,000 people supporting Monique Ryan’s indexation petition are probably under the impression that a lower-of inflation or wage increase system would save them money in the future.

Once these petition supporters are told that the WPI is already back above CPI will they think that the lower-of CPI or WPI policy addresses their grievances? As of the December quarter 2023 CPI was only slightly lower than WPI, but by the time this policy is being debated in Parliament I expect WPI will comfortably higher.

CPI is a good base indicator for HELP indexation because, unlike the other suggested indicators, policymakers have both the desire and the tools to keep it at 3% or below most of the time. For this reason, neither my proposal for a fixed maximum indexation rate nor the lower-of CPI or WPI system will save HELP debtors money in most years. They are just different ways of managing the risk of occasional inflationary spikes.

The lower-of CPI or a fixed maximum indexation rate is a simple guarantee, which requires no understanding of other economic indicators or why they go up or down. A legal commitment that HELP indexation will never exceed 4% is something every HELP borrower can understand and factor into their decisions.