The Accord implementation consultation paper on need-based funding for equity group members was released late last week, although students with disability will be discussed in a later consultation document. That leaves low SES, Indigenous and students at regional campuses for this paper.

When the Accord interim report came out I rated the principle of needs-based funding as one of its better ideas. But turning it into policy faces significant conceptual, practical and ethical issues. The consultation paper does not resolve these issues.

Funding based on needs versus equity group membership

The basic conceptual problem, in the Accord reports and this consultation paper, is that it remains unclear why needs-based funding should apply only for students designated as equity group members. With the exception of people with disabilities that require adjustments for them to participate in higher education, none of the equity group categories identify personal disadvantage. As the Accord report itself notes, groups other than the equity four are ‘under-represented’ in higher education.

The higher education system should help all its students achieve success, not just those that for historical reasons are included in the equity group list.

Many of the outcome differences we observe are the by-product of mass higher education, which brings a wide range of people into the system. There are more people who were not especially ‘academic’ at school, more people who have trouble financing their education, more people who have major responsibilities other than their studies. In a mass higher education system these students are core business.

The consultation paper recognises that non-equity students may incidentally benefit from services financed with needs-based funding, and that some equity group members do well without any special help. But the mindset on display remains in the HEPPP space of small-scale niche programs directed specifically at equity group members (see the examples in attachments A and B of the consultation paper).

Extensive acquittal requirements will limit how much ‘needs-based’ money leaks into services and improvements aimed at students in general. We are told that ‘funding is not to be used by providers to deliver any good or service they are otherwise obligated to provide through existing legislation or … is otherwise reasonably funded through an existing support program’.

So needs-based funding cannot be used for general curriculum improvement, teacher training or student support, even if these would make a bigger difference to equity and other students than niche equity programs. This does not make sense.

Types of needs

Because the paper focuses on equity groups it is vague on the actual needs to be met. This is often implied by the program types mentioned rather than directly stated. Academic support = issues with academic preparedness. Scholarships and bursaries = financial problems. Mentoring = lack of social capital.

We should start with the needs first, rather than set funding based on heuristics like equity group membership. From there universities should be flexible with what programs might help students. It could be a general program or one specific to particular types of students.

ATAR

We get a direct measure of likely academic needs in the consultation paper’s discussion of ATAR. It suggests scaling needs-based funding to reflect different levels of academic preparedness, using ATAR where available. However, this would only be for students in the equity groups, not for students generally. Effectively, it would be way of paying less or zero need-based funding for equity group students who are high academic achievers. This is a missed opportunity to tackle real academic needs at scale.

I know some readers object to ATAR for admissions. Academic ability is not the only attribute relevant to university study or future careers. It should not necessarily trump all these other attributes in deciding who to admit. But no other metric can predict academic risk as well, and through that the likelihood that a student will seek or be offered academic support (as required by the support for students policy).

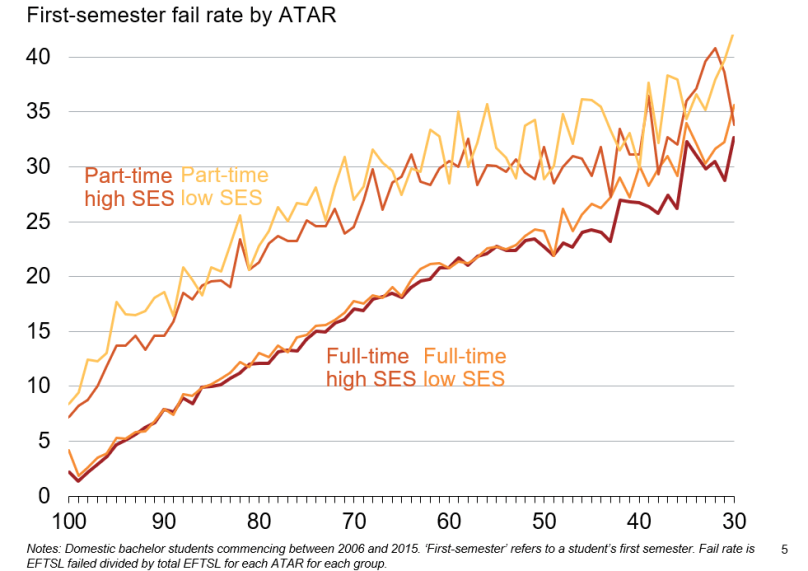

The chart below is Grattan Institute analysis using unit record enrolment data. ATAR is far more powerful than SES in predicting the risk of subject failure. For full-time students SES is near irrelevant to failure risk for ATARs above 50. We can see however that part-time study significantly increases risk beyond ATAR itself, and that for low SES students part-time study poses higher risks than for high SES students.

Part-time study often signals other responsibilities, some of which higher education policy can do nothing about, but Youth Allowance/Austudy/Abstudy can reduce the need to work long hours in addition to studying. Income support is shown to increase completion rates.

If ATAR is highly predictive of academic preparedness and low SES has only a small amount of predictive power net of ATAR, which should be used for academic ‘needs’ funding? To me it is easy: use ATAR and other indicators of prior academic achievement for all students. This would also create greater coherence between funding policy and the support for students policy.

The ethics of using low SES to allocate resources

So far as I am aware, nobody argues (as in providing reasons supported by evidence) that our current low SES definition – living in an ABS area classified as the lowest quartile of geographic areas by the Index of Education and Occupation – is an accurate measure of SES at the individual level. As I said in my post on managed extra places for equity students (avoiding its misleading official name), it produces both false positive and false negative classifications of individual students as being disadvantaged or not.

But the government just assumes, without arguing the point, that the definition is ok. It proposes giving people in the lowest IEO quartile an extra chance at a CSP and extra funding to increase their chances of success.

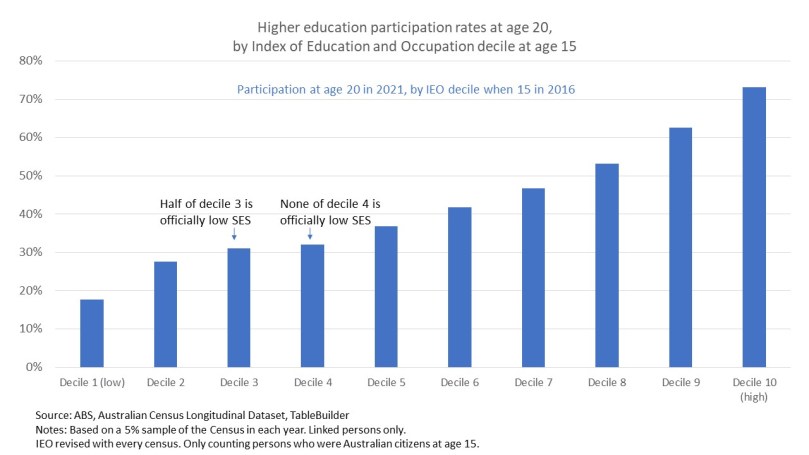

The chart below – higher education participation rates at age 20 by IEO decile at age 15 (to improve accuracy) – highlights the false negative problem. Someone living in a decile 4 area, with a higher education participation rate virtually identical to decile 3 (which is half low SES), would not be eligible for preferential places or needs-based funding. For funding purposes decile 4 residents would be treated the same way as students in deciles 9 and 10, which have participation rates that are twice as high.

Problems for universities

For universities these arbitrary distinctions are hard to implement on the ground. They can’t easily give the computer says no response. ‘Sorry, your home address SA1 is not classified as low SES, you’re on your own’. If someone has a higher education need, they should not have to say where they live or give their family history before getting help. The consultation paper recognises that in practice supports funded by needs-based funding will be spent on non-equity students who need help, while not providing any additional funding for those students.

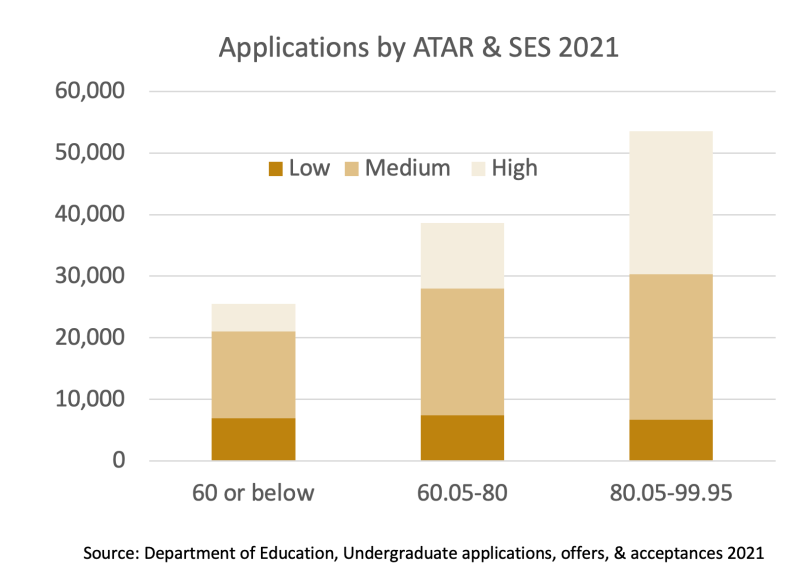

As most Australian students enrol in a university within commuting distance of their home, this means that universities in catchment areas corresponding to SES SA1s above the lowest quartile would take students with high needs but get no additional support. As the chart below shows, defining low ATAR as 60 or below, most potential students with above-average academic needs are not classified as ‘low SES’.

Reliance on the weak SES proxy of living in a SA1 in the lowest IEO quartile also means that, due to the ABS 5-yearly Census updates of SA1 IEO classifications, universities can have volatile funding.

According to the government’s equity ‘performance’ statistics, low SES students at the minister’s favourite university, Western Sydney, dropped 37% between 2020 and 2021. As education levels in Western Sydney’s catchment areas increase so do their IEO rankings. I doubt that need levels of WSU students changed by anything like that amount.

Regional campuses

Regional needs-based funding is based on campus location rather than where the students come from. Campus location as regional or not can also be affected by reclassifications. I’m not sure whether Sunshine Coast or Wollongong university campuses are affected by the latest changes below, the risks are clear. If the money is based on the regionality of the campus rather than the students, it is an all or nothing policy.

The consultation paper says that current equity programs would be replaced by need-based funding. Job-ready Graduates moved the regional loading from the Commonwealth Grant Scheme to IRLSAF, an equity program. This seems to mean that to get the regional campus need-based funding money, universities will have to participate in the same micro-program, high-acquittal approach as applies for low SES students.

This would carry forward the JRG conceptual error. The loading for regional campuses is justified mainly by their difficulties in getting economies of scale, lack of which leads to higher average per student costs. The last cost report found that regional university costs for bachelor degree students were 10% higher per EFTSL than metropolitan universities.

We can’t solve regional university cost problems by requiring new student support programs and adding new acquittal costs.

EFTSL versus headcount

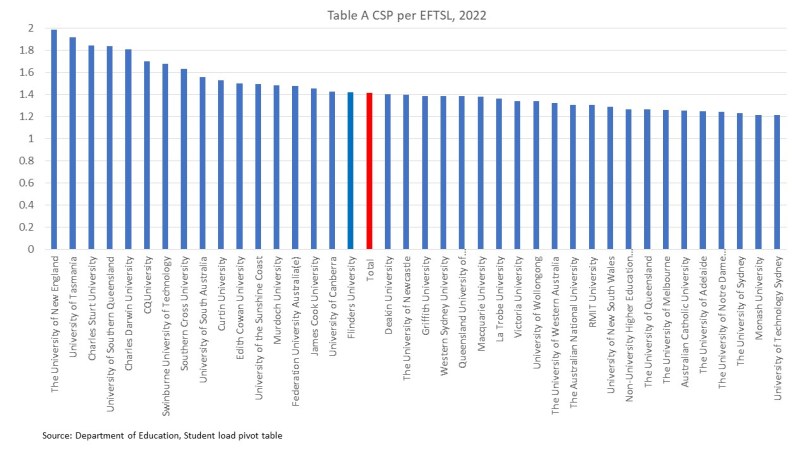

One idea proposed last year that I thought had merit was needs funding based on headcount rather than EFTSL. Especially for non-academic matters, support needs are likely to be more closely linked to the number of people than the number of subjects. As the chart below shows, students per EFTSL vary widely from primarily on-campus universities in the 1.2 to 1.3 range to nearly 2 students per EFTSL at UNE.

Needs-based funding for Indigenous students and students with disability would also be more strongly related to headcount than EFTSL.

As equity targets will be in headcount – directly or as a % of all headcount enrolments – this would also point towards an at least partly headcount based needs funding system.

But without discussing the headcount alternative the discussion paper says need- based funding will use EFTSL.

FEE-FREE Uni Ready places

The FEE-FREE Uni Ready places are not mentioned in the consultation paper other than as part of the government’s policy framework. I think this means that needs-based funding is already built in. If so, this is sensible. It provides a way of delivering initial support to students without the arbitrary constraints of the needs-based funding system.

The dollars

This is a conceptual paper, not a funding one. I did not expect any dollar amounts. But I had hoped to see some thinking about the methodology for assessing reasonable costs. It is not there (although whatever it is will be indexed to CPI). In practice, the funding level will be whatever the minister can get out of Cabinet. If he has to resort to rip-off visa application fees for international students to fund paid pracs and FEE-FREE Uni Ready places the signs aren’t good.

Conclusion

Most of the flaws in the consultation paper are inherited from the Accord final report. But it is infected by the Department’s propensity to increase bureaucracy at every opportunity. As in the consultation paper on managed EFTSL growth, this one criticises existing programs for being ‘complex’ before recommending another complex scheme with large volumes of reporting back to Canberra. Along with the Department’s attempt to disqualify people who know something about higher education from being appointed to ATEC, the Accord response is starting to look like a make-work scheme for DofE bureaucrats.

Thanks as always for your posts Andrew.

I found myself nodding in agreement with so much of what you wrote – particularly re the general need for ALL students for “general curriculum improvement, teacher training or student support“.

Here’s hoping someone is listening!

LikeLike