My paper on international student policy – new migration controls and proposed enrolment caps – is published by the ANU Migration Hub today. Some key points appear in The Conversation.

Compared to what I have already written on caps – how actual enrolments will fall below the caps and why even the government’s own agencies doubt the policy’s feasibility and fear its consequences – this paper explores the cumulative consequences to date of migration policy changes.

These consequences are already significant for vocational education and some higher education providers. This raises the question of how necessary the caps are to achieve the government’s policy goal of bringing down net overseas migration.

The policy timeline

Since October 2023 we have witnessed one of the great policy backflips of Australian political history. The Albanese government has turned from supporting the revival of international education – granting a record number of student visas in 2022-2023, extending the temporary graduate visa – to pulling almost every policy lever short of shutting the industry down to reduce international student numbers. International education now keeps political company with live sheep exports, fossil fuels, and vapes retailing.

Counting the changes is not straightforward but the list below has nine migration policy changes that are already in place that are directly intended to, or will incidentally, reduce the number of current and former international students in Australia. These are:

- Visa processing priorities, reducing enrolments in education providers rated as having students with higher risks of migration irregularities (announced and implemented December 2023);

- Increased savings required before getting a student visa (October 2023 and May 2024);

- Increased English language requirements for student and temporary graduate visas (announced December 2023, implemented March 2024);

- Greater use of ‘no further stay’ conditions on student visas (public from March 2024);

- A requirement to show ‘logical course progression’ if applying for another student visa as part of a new genuine student test (March 2024);

- No onshore student visa applications for visitor visa holders (announced June 2024, implemented July 2024);

- No onshore student visa applications for temporary graduate visa holders (announced June 2024, implemented July 2024);

- Shorter temporary graduate visas (announced December 2023, implemented July 2024);

- More than doubling the student visa application fee (announced and implemented July 2024).

A tenth migration policy change, abolishing points commonly used by former international students to secure points-tested permanent residence visas, has been foreshadowed.

Changes in student demand

Some policy changes are specific to the location of the visa applicant, so the paper’s analysis looks at offshore and onshore applicants separately.

To try to identify timing effects of policy change I used visa data on a monthly basis. To understand whether these figures show significant change or not I needed a comparison period.

Usually trend analysis would include the prior year, 2022-23, now that we have the full 2023-24 data. But this would exaggerate the effects of policy change, since 2022-23 was an abnormal year. Pent-up demand after the COVID border closure period inflated applications. Visa grants were boosted by these applications and bureaucratic effort to clear a backlog of unprocessed applications. As of 30 June 2022 more than 120,000 student visa applications were queued up, compared to 30-something thousand at the equivalent times in the pre-COVID years.

2020 and 2021 were outlier years at the other extreme, being atypically low. My solution was to average 2017-18 and 2018-19 numbers to represent more normal pre-COVID years.

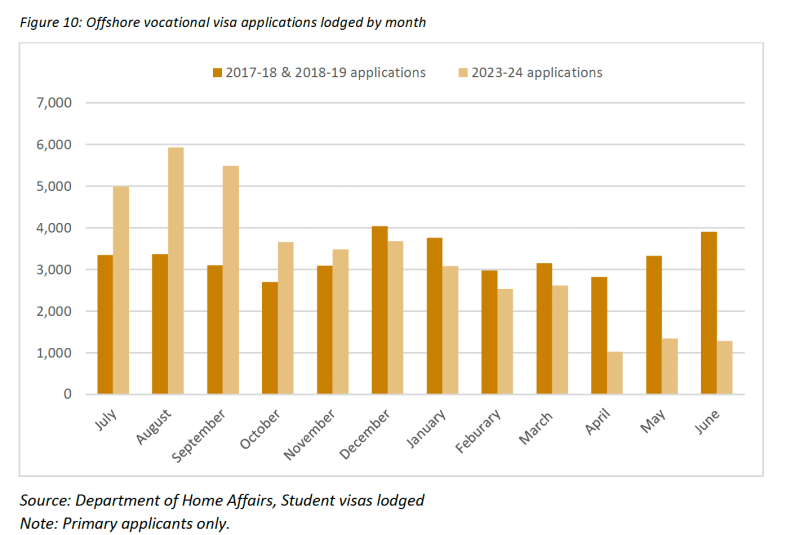

Offshore demand – vocational education

Offshore vocational education applications were very strong compared to the comparator years in July to September 2023 and still good through to the end of 2023, as seen in the chart below. The first of the increased savings requirements in October 2023 may have affected demand, but overall it remained strong.

But vocational offshore applications crashed in the first half of 2024. April to June 2024 applications were low not just when compared to 2017-18/2018-19, but to any non-COVID months going back to the start of the current statistical series in 2005-06.

In March the minimum English level required for a student visa was increased and the new genuine student test, replacing the old genuine temporary entrant test, came into effect. This requires applicants to answer more detailed questions about their plans to come to Australia.

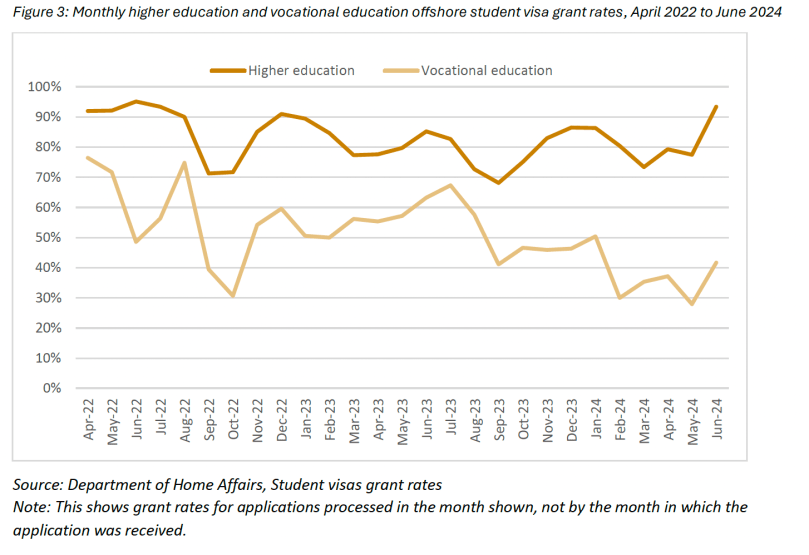

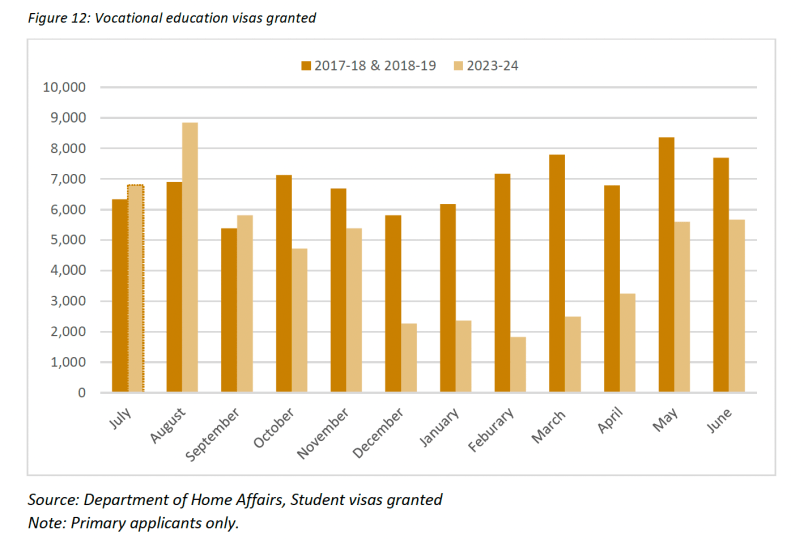

The downward spiral of vocational visa grant rates to record lows, as seen in the chart below, could also have reduced demand, as would-be students decided that their chances of success were too low.

The June 2024 data is before the 1 July 2024 more than doubling of the visa application fee to $1,600. This will further discourage risk-averse prospective students.

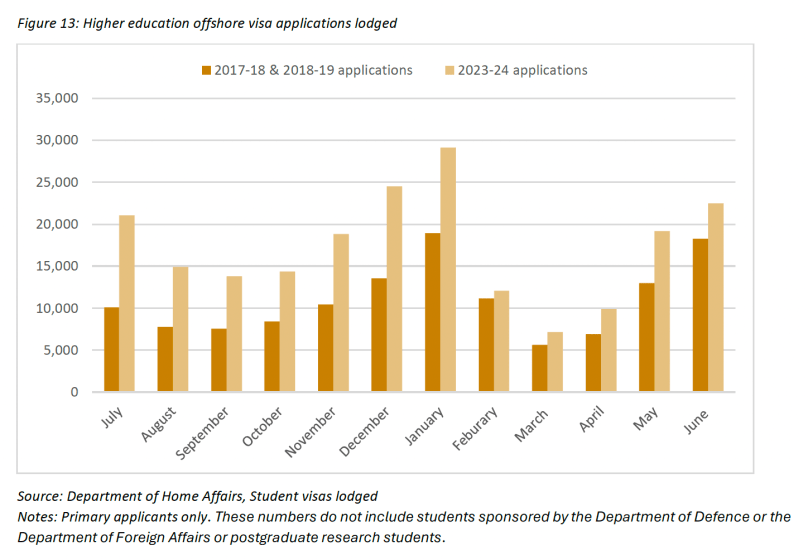

Offshore demand – higher education

For higher education the offshore applications story is very different. While February to June 2024 figures show some cooling compared to the preceding 2023-24 months, they are still above the comparator years.

Higher education applications over the coming months are a key indicator of whether migration policy alone can curb international student numbers. The numbers below don’t include any disincentive effects from the $1,600 visa application fee.

Changes to the temporary graduate visa coming into effect on 1 July 2024, which reduce their length and decrease the maximum age for a visa, affect higher education more than vocational education. However one of the most migration-sensitive source markets, India, is partly exempt from these changes due to an Australia-India trade agreement.

Foreshadowed changes to permanent residence points may be yet to influence the higher education market.

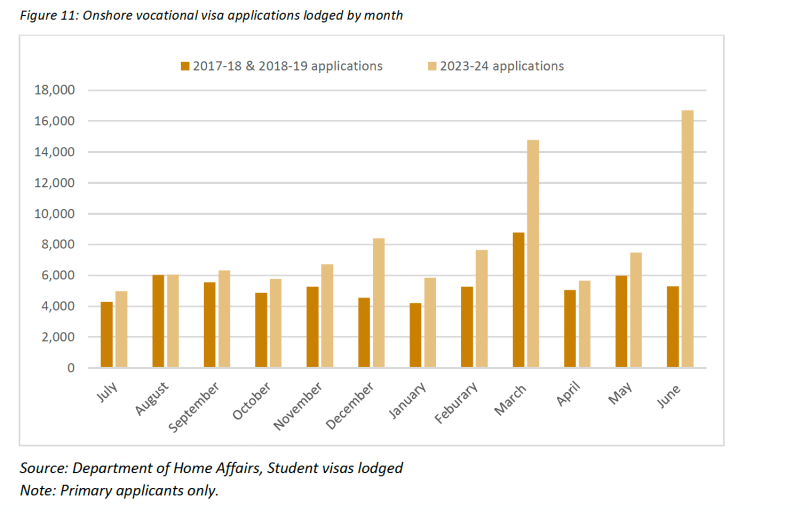

Onshore demand – vocational education

Onshore demand shows clear sensitivity to policy announcements – probably people in Australia are more aware of policy changes.

On 15 March 2024 the government told international education stakeholders that 23 March 2024 was the implementation date for the genuine student test. This included greater scrutiny of applications from visitor or temporary visa holders, and more evidence of logical course progression from people wanting another student visa. Applications lodged prior to 23 March would be assessed on the old rules, creating a strong incentive to get applications in before then. As the vocational education figures below show, applications spiked significantly in March.

On 12 June 2024 the government announced that no student visa applications from onshore visitor or temporary graduate visa holders would be accepted from 1 July 2024. My paper shows that applications from temporary graduate visa holders had already fallen to low levels for other reasons, but that applications from people with visitor visas are significant (see also this post). Unsurprisingly, applications spiked in June 2024 to get in before the rules changed.

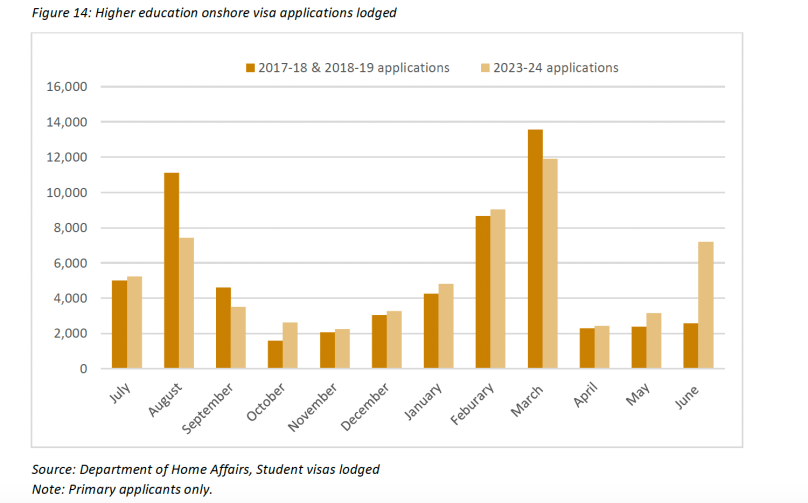

Onshore demand – higher education

For higher education, onshore applications through 2023-24 are generally similar to the comparator years. But higher education also shows the June spike, before the restrictions on onshore applications came into effect.

We may see some onshore visitor and temporary graduate visa holders blocked from applying for a student visa return home and reappear later in the offshore statistics. But given the ban on onshore visitor and temporary graduate visa holders making student visa applications we can expect onshore applications to decline significantly for July 2024 and subsequent months.

Visa grants

The visa processing priorities policy has caused major delays for applicants hoping to attend education providers rated as higher migration risk. In December 2023, 50% of vocational visas were processed in about two months. By July 2024 this has blown out to six months.

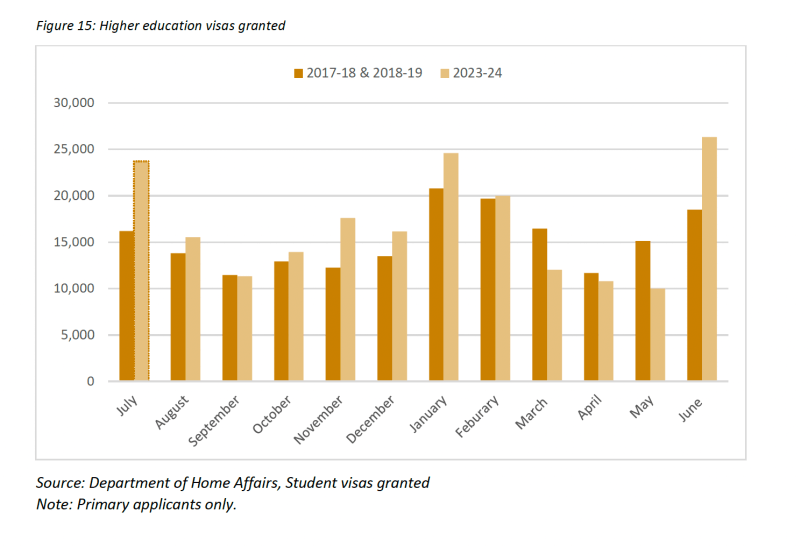

Overall higher education visa processing is much faster, but as of July 2024, 10% of higher-education visa applications had been in the system for four months or more.

These delays mean that visa grants are a lagging indicator. Most of the visa grants made in the last few months would have been judged on the criteria applying before 23 March 2024. Unless higher-risk would-be students don’t apply, applications submitted after that date will have lower success rates – which, as one of the earlier charts showed, were already below historical success rates

With these caveats, we can see that monthly vocational education visa grants have been below the comparator years since October 2023, but with an increase in total numbers for May and June 2024.

For higher education, as expected from the demand figures, monthly visa grants were above the comparator years up to February 2024 (by a small margin in that month). From March to April 2024 visa grants are below the pre-COVID levels, with a spike in June 2024. In higher education June is normally a busy month for visa grants ahead of the second semester commencing intake.

Overall trends

Due to the exhaustion of pent-up demand and multiple changes to migration rules and incentives – with more to have their main effects after the months in this post’s charts – we can be confident that international student demand for the rest of 2024 will be well below that observed in the second half of 2023.

For vocational education demand will also be well below the comparator years of 2017-18 and 2018-19. While the slow clearing of backlogged visa applications might produce some moderately strong visa grant months in the second half of 2024, the 2025 outlook for international vocational education commencing students is very bad. The caps will be political theatre without practical consequences for the vocational education providers that cannot get students into the country anyway.

For higher education some providers have already been badly affected by the visa processing priority system. As application numbers moderate there is no justification for this system remaining in place. But overall, at least to June 2024, we are probably not seeing a sufficient decline in visa grants for the government to be confident that migration policy alone will keep numbers sufficiently down.

This evidence may come as more 2024 visa application and grant data is released. But Cabinet – according to media reports due to consider the caps today – would probably not be convinced by the data to date to put the caps on hold.

Thank you for your articles. I could not agree more here are many benefits of the students – one is the boost to tourism,. One of my students explored the impact of international students on tourism – most international students are visited at least once by their families and they do not spend on just a day in Melbourne but venture across the country bring revenue to a host of secondary locations.

Keep up the good work.

LikeLike