The debate on international student caps is mostly at the level of principle. But the capping bill‘s wording is also critical to its effects. A key issue is whether the cap is based on a cumulative total of enrolled international students through a year or the total on specific dates during the year. A cumulative count will have much more serious effects on students and education providers.

The cumulative count wording of the bill

The most natural meaning of the current bill is that the count is cumulative – ‘a limit’ (singular) on the ‘total’ number of overseas students enrolled in one or more years. This means that the cap is driven by the peak number during the year.

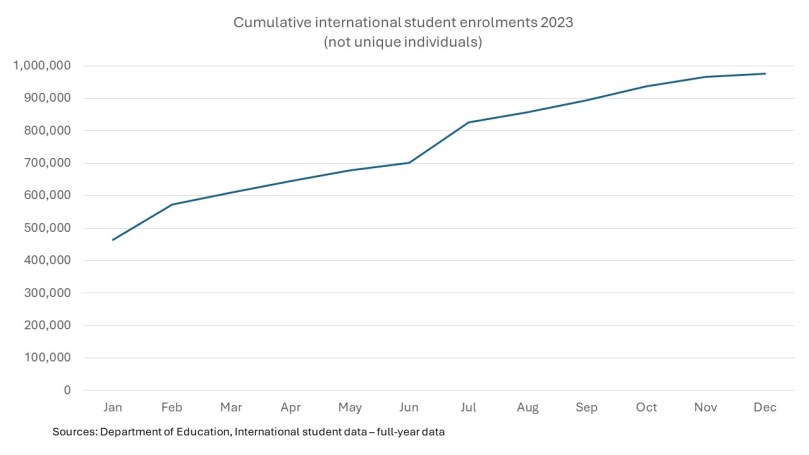

A cumulative number increases during the year, as seen in the enrolments chart below. So far as I know, the cumulative month-by-month count during the year of unique enrolled student visa holders – the basis of the bill – is not currently available. But we do know that by the end of 2023 741,756 student visa holders had been enrolled at some point during that year (an average of 1.3 enrolments per person).

The cumulative total is much higher than the number of enrolled student visa holders at any given time during the year. This is because international students, like other students, are in annual cycles of starting courses, completing courses and dropping out of courses.

Cumulative versus point-in-time

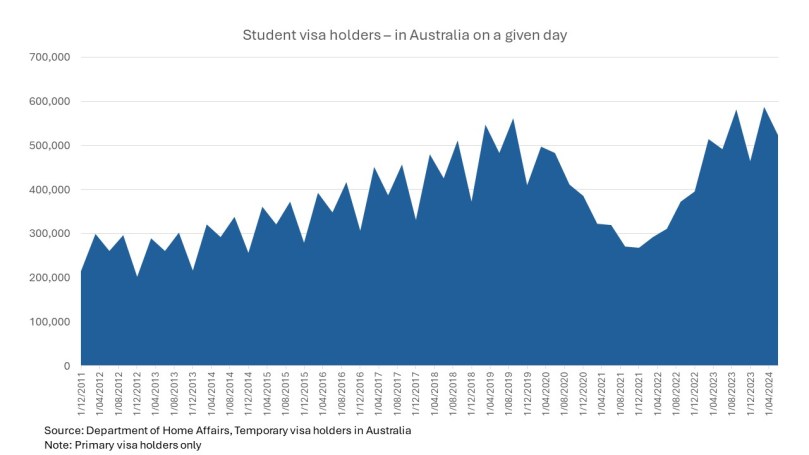

While we don’t have a cumulative count of unique student visa holders the Department of Home Affairs reports the number of student visa holders in the country on various dates during the year.

This is not the same as enrolments on a given day. Some enrolled students are out of the country the day of the count but will return – see the dips and recoveries around holiday periods in the chart below. Some student visa holders are still in Australia but are no longer enrolled (usually visas last a couple of months after the expected course end date). But the Home Affairs number is as close as we get to the number we want, unique student visa holders enrolled at different times of the year.

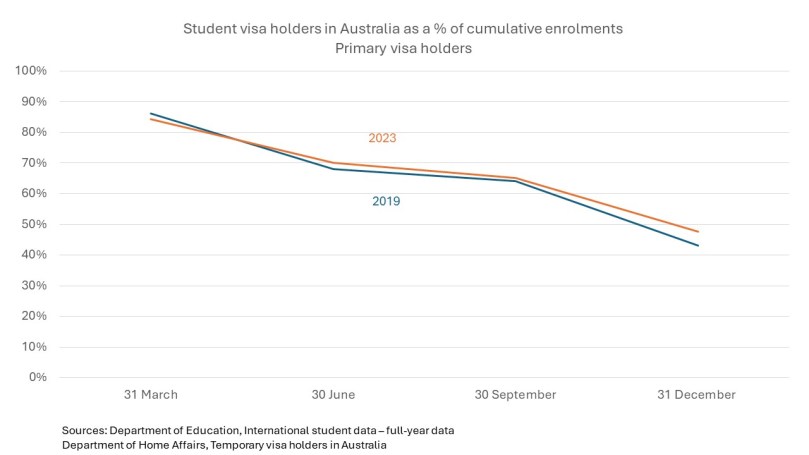

Due to enrolments and visas ending during the year, the point-in-time numbers are more stable than the cumulative count. This means that the point-in-time number falls as a percentage of cumulative enrolments to that time. The 31 December date is misleading due to enrolled students being away on holidays, but during second semester, at 30 September, the number of student visa holders present in Australia is slightly less than two-thirds of cumulative enrolments to that date.

A cumulative total requires empty student places for much of the year

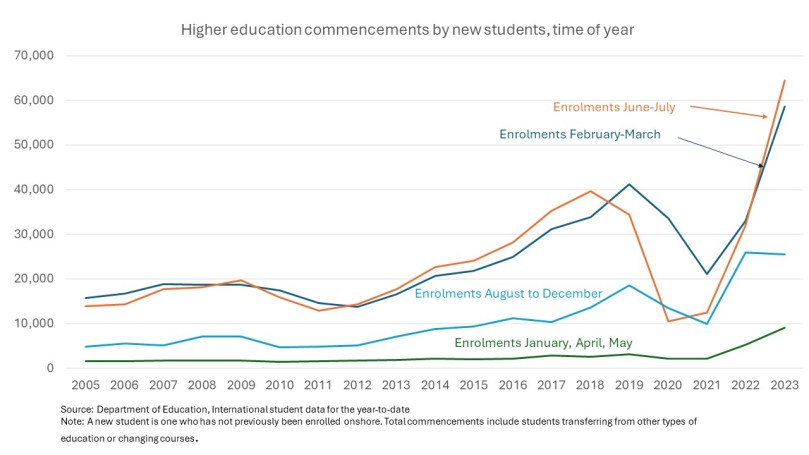

As the chart below shows, second semester higher education starts are more common than first semester starts. This aligns with the ends of academic years in source countries.

A policy based on cumulative student counts does not fit well with a system reliant on second semester starts. Education providers would not want to keep empty places within their cumulative cap for second semester starts, with consequent loss of revenue. They could try to insist on first semester starts, but that would leave international students filling in time between finishing their schooling or previous post-secondary course and starting their further education in Australia.

The cumulative cap is not necessary for the population control policy goal

For the capping bill’s policy goal of moderating Australia’s international student population a cap based on a cumulative annual total is not necessary. What matters is how many student visa holders are living in Australia at a given time.

If the cap was based on set dates during the year the students completing their courses or dropping out in first semester could vacate places within the cap. They could then be replaced with new students starting courses in second semester, with no net effect on the overall student visa holder population.

I don’t have firm ideas on how often there should be an enrolment check, given the various teaching period systems around the sector. But at least twice a year and perhaps more often. If reports of also capping international students as a percentage of all students are correct then it would make sense for capping dates to be at or after census dates.

Conclusion

A cumulative student count capping system will cause inconvenience to international students and revenue loss to providers in excess of what is required to achieve population control.

While I think the caps should not go ahead at all, an amendment to count students at set dates would cause less harm than the bill as drafted.