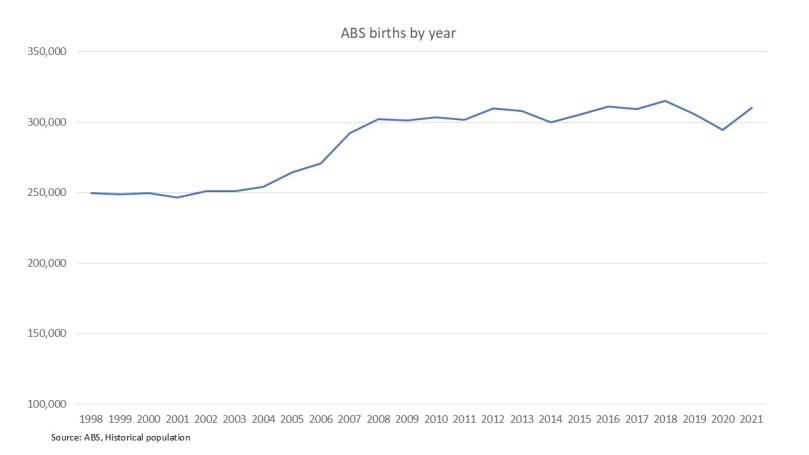

Since the late 2010s I have promoted the idea that the so-called ‘Costello baby boom’ cohorts will arrive at university age from the mid-2020s, increasing school leaver demand for higher education. As the chart below shows, annual births go from around 250,000 in the early 2000s to around 300,000 later in the decade.

Demographers are sceptical of how much effect mid-2000s pro-family policies had, but former Treasurer Peter Costello’s line that ‘if you can have children it’s a good thing to do – you should have one for the father, one for the mother and one for the country..’ was sufficiently memorable that this baby boom has his name attached to it.

As these cohorts approach university age this post takes another look at the data.

The count of Australian born young people

For births I used ABS data because of its convenient time series, but it is not perfect. It counts registrations of births, which can be delayed or missing. The numbers differ slightly from data collected from health professionals such as midwives.

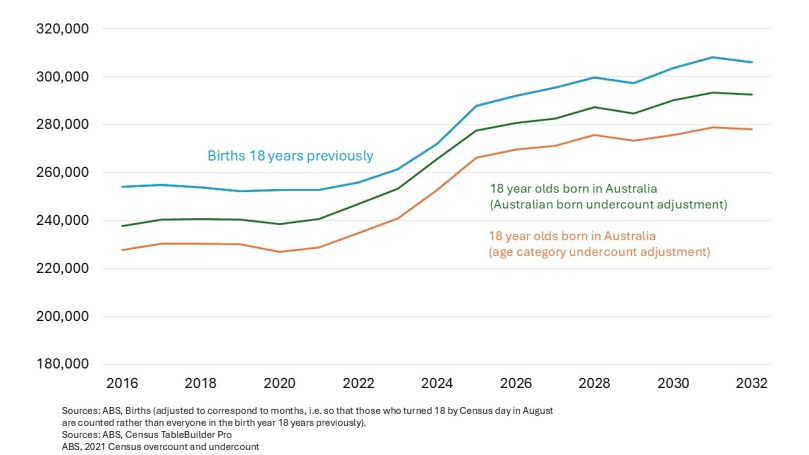

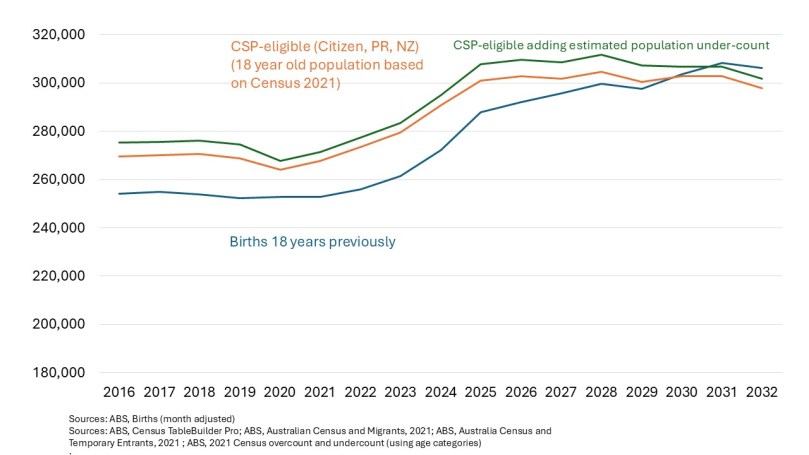

These small differences cannot explain the chart below derived from Census 2021 data. What this chart does is project back and forward the 18 year old population of people born in Australia. For example, the age 18 projection for 2032 is based on children who were 7 years old in the 2021 Census. The chart then compares this number with the births figure 18 years previously.

The ABS acknowledges that the Census undercounts the true population. I have used a couple of their person characteristic general undercount estimates to inflate the relevant populations as reported in the ABS Census TableBuilder Pro. But the higher of these two numbers still leaves me between 10,300 and 14,800 short of the original birth cohort for the mid-2020s and beyond.

Deaths

Over the years 2005 to 2021 on average there were just over 1,100 deaths per year of babies aged less than one year, and about 800 deaths per year of children/young adults aged 1 to 18 years. These numbers includes all deaths, not just people born in Australia, but explain some of the discrepancies between births as originally recorded and the 2021 count of people born in Australia.

Short-term visits overseas

Another reason for the Australia-born figures being lower than expected is that some of them are not in Australia. Australians overseas are not counted in the census.

Although it was much less of a factor than usual for the August 2021 Census, large numbers of Australians are normally outside of Australia, mostly on a short-term basis, on a given day. It’s quite normal for 800,000 Australian citizens to depart Australia each month. (Again, this includes people not born in Australia.)

Potential long-term departures of the Australia-born population

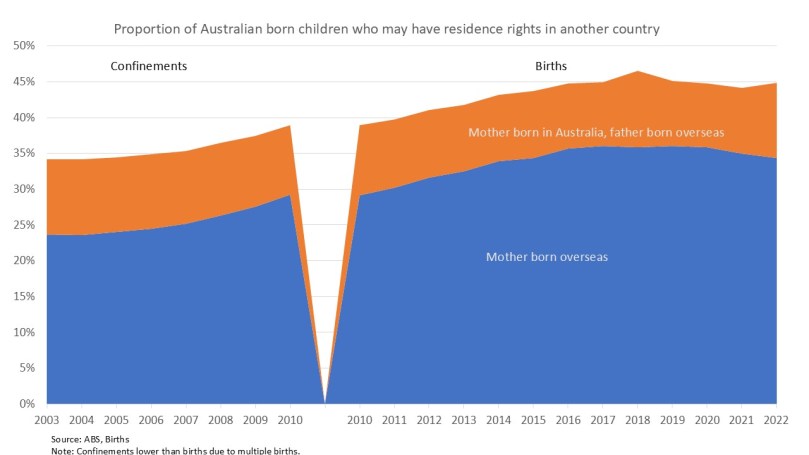

Immigrants to Australia are at least partly responsible for an increasing proportion of births, as seen in the chart below. For the baby boom cohorts the immigrant share increases from about 35% with at least one overseas-born parent in the mid-2000s to 39% at the end of the decade. It more recent times about 45% of babies born in Australia have at least one overseas-born parent.

While residence rights vary, a large percentage of young Australians could live long-term in the country of their parent(s). It would not be surprising if some of them left Australia because their parents returned home.

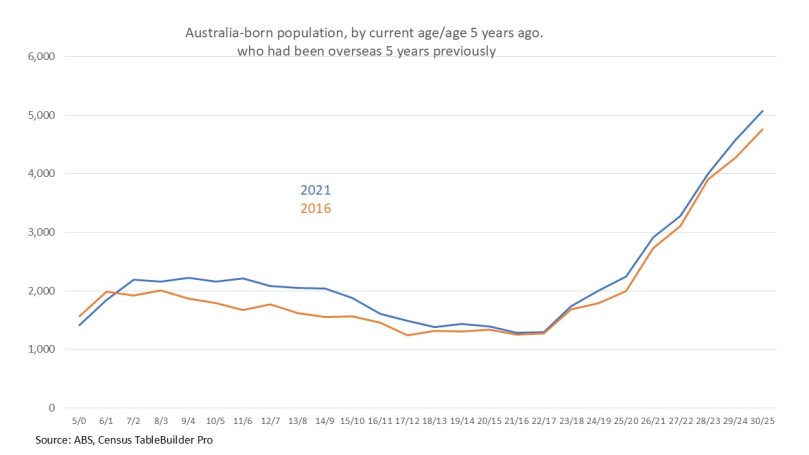

Unfortunately I can’t find any age-based Australia-born net overseas migration figures, but we can draw some inferences from Census questions of those who were overseas 5 years previously. Obviously, these are only the people who returned. It also excludes people who were away for less than 5 years (the Census has a one year question, with 529 Australia-born 18 year olds who had been overseas a year earlier, but due to COVID travel restrictions this question reveals less than it would normally).

If the 2026 Census has similar results to 2021 and 2016 it suggests that some of the younger cohorts I am extrapolating forward to the year they should turn 18 are down about 2,000 due to overseas absences. I can’t see the people who were in Australia in 2021 but won’t be in subsequent years. There will be some, but overall I read the chart as showing early career working overseas, with a tendency to return as children get older.

Migration to Australia

While some Australia-born people leave Australia permanently or long term, in non-COVID years Australia is a net importer of residents. In the chart below, from 2016 to the mid-2020s we can see that the people in the Census that I identify as CSP eligible – that is they hold citizenship, permanent residence or a NZ special category (sub-class 444) visa – exceed the number expected based on births 18 years previously by around 20,000. But then the gap starts declining and turns negative in 2031 and 2032.

Will these numbers change?

Based on the second-last chart I expect that, over the coming years, some Australia-born people will return to Australia as they reach secondary school and post-school education ages.

The projections also do not take into account of additions to Australia’s population between now and the early 2030s.

One number I have never seen quantified in migration figures is the arrivals of people who have citizenship by descent – that is, they were born overseas to one or both parents with Australian citizenship. About 16,000 such grants are usually made each year, but there is no data on how many of them use their CSP eligibility. About 250 annual surrogate births overseas – in recent years, I am not sure about the 2000s – also have citizenship by descent. I expect that most surrogate babies grow up in Australia as de facto additions to the local birth cohort.

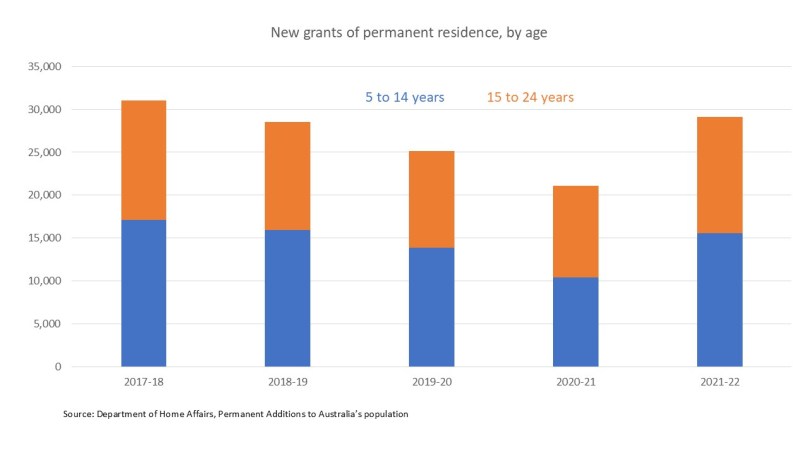

On top of new arrivals of citizens born overseas, non-citizen arrivals will add to the population. As the chart below shows, for obvious COVID reasons, 2019-20 and 2020-21 had fewer new permanent residents than usual (plus a higher share of onshore applicants converting from a temporary visa rather than new arrivals). As a result, fewer permanent residents were in Australia on Census day 2021 than would otherwise have been the case. Young people obtaining PR in the coming years will increase the school leaver population. By how much remains an open question, given that migration is an unstable policy area.

Some migrant groups have double or more the university participation rates of people born in Australia who speak English at home. This means that the level and composition of migration is important to future demand for university.

Implications for school leaver numbers

Without further positive migration effects on the totals, on Census 2021 figures we are still looking at an increase in CSP-eligible 18 year olds of about 38,750 between 2020 and 2030, compared to 50,800 extra prospective students based on the birth cohort.

I think migration – both returning citizens and new arrivals – will push up CSP-eligible numbers. But migration flow, both into and out of Australia, is a source of volatility in estimating the future pool of potential domestic students.