Some universities and vocational education providers would prefer enrolment caps to ministerial direction 107, which consigned their offshore student visa applications to the end of the visa processing queue. 107 tells the Department of Home Affairs to give processing priority to applications for schools, postgraduate research, and higher education institutions with a low immigration risk rating.

The education minister has said that ministerial direction 107 will go if the caps bill passes.

While 107 should be repealed, as it unfairly penalises some student visa applicants and education providers, like Claire Field I think the sector over-rates the benefits that would follow. 107 is blamed for other things that happened around the same time that would not be affected if it went.

These other things include the resources Home Affairs allocates to student visa processing, changed practices in applying visa eligibility criteria, and new visa rules.

Student visa processing levels

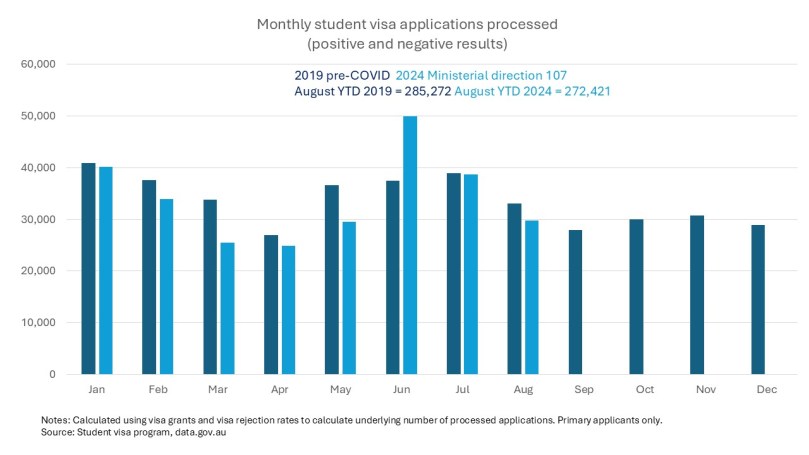

From November 2022 to July 2023, Home Affairs put significant effort into clearing a student visa backlog. On my calculations, in those nine months they processed – counting both grants and rejections – 483,199 visa applications (primary visa holders only). That is 54% more than the equivalent number pre-COVID, between 2018 and 2019.

In the second half of 2023, shown in green in the chart below, monthly visa processing dropped back to levels that were similar to 2019. Ministerial direction 107 was announced in December 2023, but that was the fourth month of more normal pre-COVID visa processing volumes.

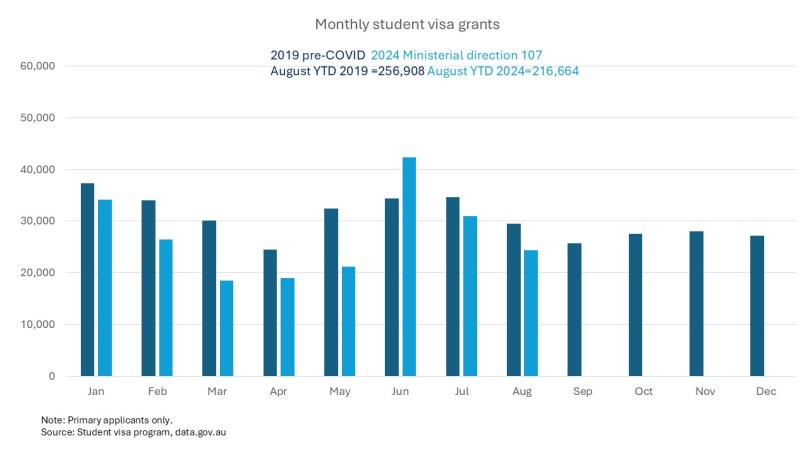

Removing 2022 and 2023 to make the chart easier to read, we can see that in 2024 visa processing was below 2019 levels except for a surge in June. That surge meant that visa processing is, in year-to-date to August terms, down by less than the other months might suggest compared to 2019 – 13,000 or 4.6% fewer applications processed.

The sources of provider and student pain – applications made compared to applications processed

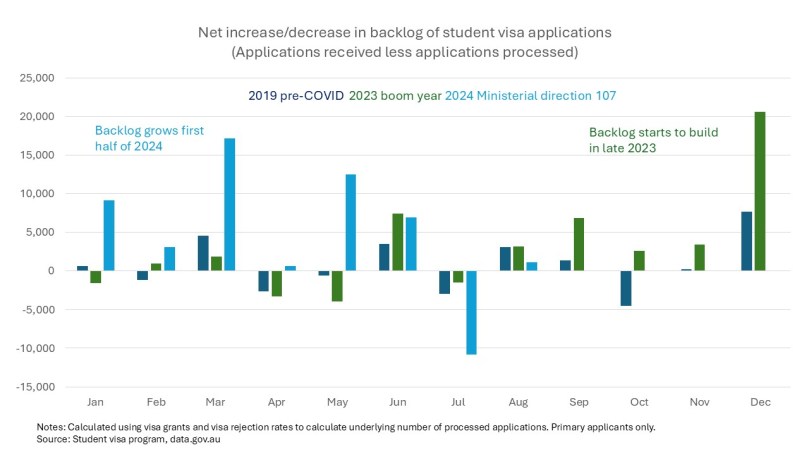

Compared to 2019, Home Affairs appears to be only moderately driving with its foot on the brake for applications processed in 2024. The problem for students and providers is that, until the last couple of months, total applications were still high compared to pre-COVID levels (offshore down, but onshore up).

As the chart below shows, in every month but one from August 2023 to August 2024, the Department received more student visa applications than it processed. In 2019, by contrast, applications processed exceeded applications received in five of the twelve months. As applications fall, in the second half of 2024 and beyond, the imbalance between applications and processing capacity should moderate, but the backlog as of August 2024 must be significant.

The sources of provider and student pain – grant rates

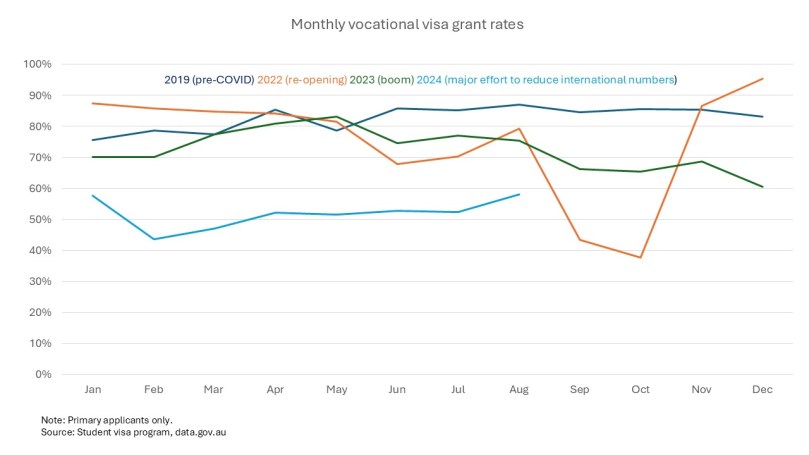

Along with processing fewer visa applications, compared to the past Home Affairs rejects more of the applications it processes. Because vocational and higher education are so different on this indicator I report them separately.

The previous government’s early 2022 decision to lift restrictions on student work hours, which were not re-imposed until mid-2023, attracted students who wanted to work rather than study. Home Affairs realised what was going on and visa grant rates went down, as seen in the chart below (other than the late 2022 approve-almost-anyone backlog clearing; see the very high processing numbers in the first chart).

Low vocational education grant rates have nothing to do with ministerial direction 107. These are due to mix of bad incentives attracting non-genuine students, tougher (and sometimes inconsistent) application of the rules, and new rules. Increased financial requirements in October 2023 and May 2024 might have had an impact here. The new genuine student test and increased English language requirements took effect in March 2024, although most of the visa processing in the chart below was under the old rules (the change applied to new applicants).

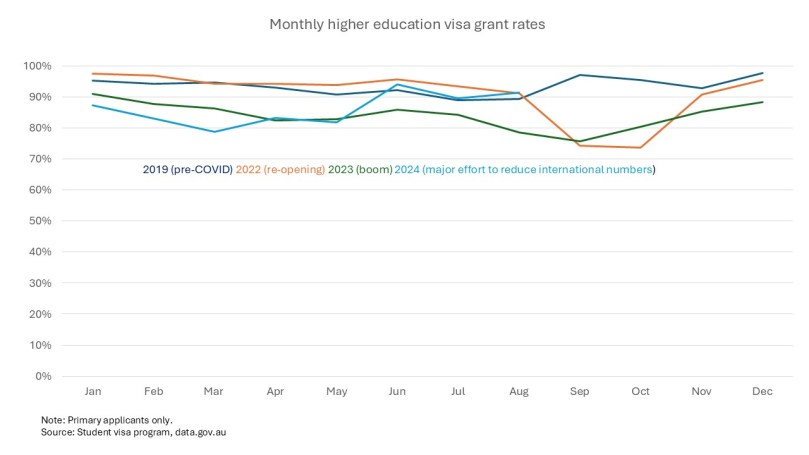

In higher education visa grant rates are always higher than in vocational education. As with vocational education, however, we can see a crackdown in September and October 2022, the spike in late 2022, and then consistently lower rates in 2023 compared to 2019. Ministerial direction 107 should have improved grant rates as Home Affairs processed fewer high-risk applicants. This is evident from April.

As the chart below shows, the interaction of fewer applications being processed and a lower approval rate is that, in August year-to-date terms, 40,000 fewer visas have been granted in 2024 compared to 2019, or a 15% decline.

The consequences of lifting ministerial direction 107

A Home Affairs bureaucrat told the international student caps Senate inquiry that repealing direction 107 ‘would see us processing applications more in date order than in priority order’.

Processing applications according to when they were received would reverse the hierarchy of provider visa pain.

Applicants for institutions with high risk ratings would move up the queue, due to the many old and unprocessed applications.

In higher education, we can expect the grant rate to decrease as higher-risk applicants are processed.

Applicants for institutions with low risk ratings, on average more recent due to 107’s priority processing, would be put back further in the queue. As their applications take less time to process there may still be some advantages to the low risk rating.

The number of visas processed

Lifting ministerial direction 107 will not mean that more visa applications are processed.

The number of visas processed is a function of the number of applications, Home Affairs staffing levels, and the time taken to assess each application.

New offshore monthly applications are in decline, but Home Affairs has a large backlog to work through. The spike in rejected onshore student visa applicants who are appealing to the AAT may divert Home Affairs resources from processing other applicants.

Given the government’s overall goal of reducing temporary migrant numbers, Home Affairs is not likely to devote more resources to student visa applications. When the government more than doubled the visa application fee, there was no plan to provide a better service to international students. Instead, the money would be used to fund various Accord-related measures for domestic students. If 107 goes, the average time spent on each visa application will probably increase, as higher-risk applications take more time to assess.

Delays will be part of the system until there is an even balance between applications received and processing capacity – possibly a deliberate part to help manage net overseas migration. Abolishing ministerial direction 107 will create a fairer student visa processing system, but not one that will see more international students being granted visas.