An earlier post looked at Robert Menzies and higher education, first as Opposition leader and then as Prime Minister, from 1945 to 1956. Despite important structural changes in the early 1950s, with the Commonwealth commencing grants to universities via the states and directly financing Commonwealth scholarships, the university sector remained small and financially weak.

In March 1956, Menzies agreed to a university policy review, what became the Murray report. This post draws on my chapter on the Murray report in The Menzies Ascendancy: Fortune, Stability, Progress 1954–1961, edited by Zachary Gorman and published last month.

The appointment of Keith Murray to review universities

By the time Menzies agreed to the review he had already decided that major changes to university policy were needed.

In his book The Measure of the Years, Menzies says that prior to his trip to England in 1956, where he first met Keith Murray in person, he told Treasurer Artie Fadden that he was initiating an enterprise that could not fail to be ‘vastly expensive’.

In December 1956 Murray was appointed as chairman. The four other members included CSIRO Chairman Ian Clunies-Ross, believed to be the subsequent report’s main author.

The Murray report

The Murray committee worked quickly and delivered its report in September 1957. Its elegant prose and frank conclusions make it, in my view, the best higher education policy report published in Australia.

The report’s criticisms included many perennial problems of Australian universities – inadequate student academic preparation, poor quality teaching, industry not doing its own research, the unsatisfactory situation of overseas students, dissatisfied academic staff, and shortages of graduates.

The report’s comments on university infrastructure were especially scathing. Students and academics were ‘overcrowded’ in ‘grossly deficient’ buildings.

Without quick action, the Murray report warned, the current ‘critical’ situation ‘may well become catastrophic’.

These serious problems could not be solved cheaply. The Murray report recommended significantly increased funding to improve conditions for students and staff and support increased enrolments.

On governance issues the Murray committee’s views aligned with those of Menzies. They assumed that university autonomy was essential, that universities could not achieve their functions without it. At the same time, ‘the days when universities could live in a world apart, if ever they truly existed, are long since over.’ Universities needed governance systems that could balance autonomy and national interests.

To reconcile these goals the Murray committee suggested an intermediary body, which following the British example they called a University Grants Committee. It would use a decentralised process for setting priorities and directions. Committee visits to universities would inform them of national needs while hearing about each university’s own plans. Based on these discussions the Committee would make recommendations to the government. The Murray committee saw a limited role for ‘earmarking’ of grants for specific projects supported by the government, where a university had agreed to it. But they thought that most grants should be for general university purposes.

The funding response

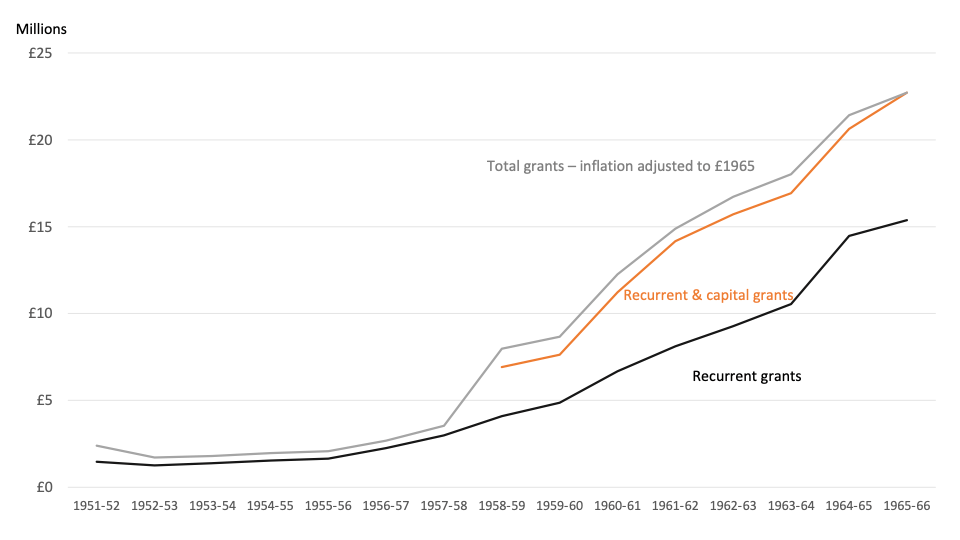

Menzies announced the government’s response to the Murray report in November 1957. It came in stages, starting in 1958. The first stage was increased grants distributed through the existing framework. These included ‘emergency’ grants for recurrent expenditure, additional funding conditional on pay increases for academics, and for the first time money for capital works. Unlike the general recurrent grants, capital funding was for specific projects.

Capital grants changed the institutional fabric of the higher education system. The 1958 university states grants legislation included an initial £75,000 contribution to purchasing a site for Monash University and preparing its building plans. Including Monash, initial capital funding was provided for six of today’s public universities between 1958 and 1965.*

The chart below shows trends in grants to states, in both nominal and real terms, from the start of the section 96 system in 1951 to the last financial year of Menzies’ prime ministership, 1965-66. While funding began increasing significantly in 1956-57, it surged in 1958-59, with a 125% boost in real terms on the previous financial year.

The Australian Universities Commission

The next stage of the government’s Murray report response was a new funding process. What the report called a University Grants Committee was legislated in 1959 as the Australian Universities Commission. The AUC would advise the government on the need for, distribution of, and conditions to be attached to money that would be paid via grants to the states and directly for the Australian National University.

The AUC was to perform its functions with a view to the ‘balanced development of universities so that their resources can be used to the greatest possible advantage of Australia.’ The AUC is a policy turning point. From this time onwards, Australia’s public universities are part of a national system, rather than a collection of state-based institutions.

The role of Menzies

Compared to another non-Labor leader, Menzies was I believe undoubtedly significant to the late 1950s direction of university policy.

The Murray review was part of a strategy by Menzies to make major changes to university policy that he knew would not be a high priority for his colleagues. The good appointments Menzies made to the Murray committee led to a high-quality and persuasive report. It probably built public and political support for reform; at minimum it raised the profile of university issues. The release of Murray’s report was, for example, a page one story in the Sydney Morning Herald.

Menzies says in The Measure of the Years that Treasury had a full opportunity to examine the Murray proposals he put to Cabinet. What he does not say, but his biographer Allan Martin does, is what Treasury thought of them. Predictably Treasury did not like them, due to the high proposed expenditure and the potential precedent of state bodies [i.e. universities] directly accessing a Commonwealth entity constituted to deal with their financial requirements.

Treasury’s concerns were ignored. Menzies told a Cabinet meeting, which he called with two or three days notice, that he would like it to ‘sit morning, afternoon and evening and reach its conclusions that night’. The Cabinet, ‘knowing that this was an outstanding event in my life, humoured me, and I am still grateful to them.’

Why did Menzies not act sooner?

One criticism of Menzies is that he took a long time to initiate transformational change for universities. By the time he announced the government’s response to Murray he had been in power for nearly 8 years – longer than most prime ministers last.

In the early 1950s Menzies was not the political giant he became in hindsight as Australia’s longest serving prime minister. After coming to power in 1949, he lost seats in the 1951 and 1954 elections. As my earlier Menzies post noted, Labor lost on seats in 1954 but had a majority of the two-party preferred vote. Menzies had to choose his political priorities carefully, to keep both the electorate and his colleagues happy. But a strong result in the 1955 election gave Menzies a fourth consecutive election victory and greater authority to act on his own initiative. He added a fifth victory at the 1958 election, after the Murray policy response.

The AUC decision

I think Menzies was also significant in deciding on the legislated Australian Universities Commission rather than the more informal University Grants Committee recommended by the Murray report.

The AUC’s detailed advice set the default policy as university expansion through the 1960s, when if university funding had remained in the normal Budget process the default would have been the previous year’s funding level. University expansion, along with the colleges of advanced education that followed the subsequent Martin report (outside the scope of my chapter), continued under Liberal governments after Menzies retired in 1966 until they finally lost office in 1972.

Conclusion

Compared to another non-Labor leader I think Menzies holding the Liberal Party’s leadership made a significant difference to the direction of university policy. Compared to a counter-factual Labor government it is harder to say what difference Menzies made. Possibly Labor would have been interventionist, but that is inference from their general policy approach at the time, not specific statements about universities.

Whatever the conclusions from these counter-factual exercises, Menzies deserves his position among the key national political figures of Australian higher education, which I see as Menzies, Whitlam, Dawkins and Gillard.

[*] Flinders, La Trobe, Macquarie, and colleges that became James Cook University and the University of Wollongong. Two other universities have links to this era. The already existing Newcastle University College became the University of Newcastle in 1965. In 1960 the South Australian Institute of Mines and Industries became the South Australian Institute of Technology and received funding under the Commonwealth’s university funding program. Its subsequent status as the University of South Australia is however still 30 years away.

Thanks Andrew, very interesting and topical

LikeLike

Thanx very much for this.

Were not increases in Commonwealth recurrent funding for universities conditional on increases in states’ grants and states permitting increases in fees, which amplified increased funding for universities. I understand that some State governments were reluctant or slow to match increases in Commonwealth grants.

LikeLike

‘dolphinmagneticc3aee434a5’ is an alias for Gavin Moodie.

LikeLike

I did not try to calcuate figures, but a Labor criticism was that universities were not getting their full potential Commonwealth amount, due to shortfalls in state grants and/or student fees.

LikeLike

Andrew, thanks for this. The Murray Report was a true breakthrough for Australian HE, something our old colleague Peter Noonan never ceased in telling me. And, as I recall, in a nice act of non-partisanship Julia Gillard pointed to Menzies HE building role in her speech announcing the Bradley Review. I think she very much saw Bradley and its outcomes in a lineage with Menzies, Whitlam and Dawkins

LikeLiked by 1 person