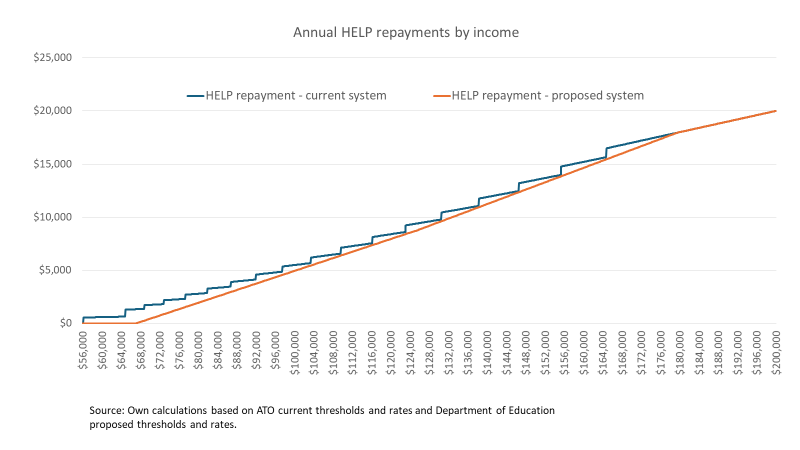

The new HELP repayment system being legislated this week will move from repaying a % of total income to a % of income above the repayment threshold, a marginal system. In introducing the bill to Parliament, education minister Jason Clare quoted Bruce Chapman on a marginal system: ‘it’s much gentler and much fairer than previously—we should have done it years ago.’

While the new marginal repayment system may be gentler and fairer, it could create more widespread disincentives to working additional hours than the current total income system.

The problem with total income systems

The Universities Accord Final Report, which guides the government’s higher education agenda, criticised the total income repayment as unfair and a deterrent to work.

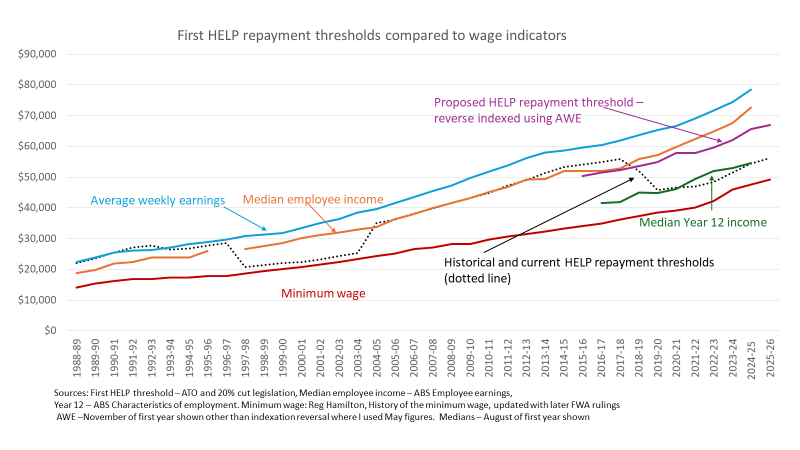

The underlying problem is that a multi-rate total income repayment system creates multiple threshold ‘cliffs’, income points at which earning $1 more triggers a big increase in student debt repayment. The most extreme cliffs are the lower income levels. Under the current system a debtor whose income reaches the $56,156 first threshold faces an increase in repayments from $0 to $561.56, plus 30 cents of income tax. By earning more the student debtor reduces their take-home pay. Repayment cliffs exist, at less extreme levels, at all 18 income thresholds in the current student debt repayment system.

A total income repayment system produces some very high effective marginal tax rates (EMTR). An EMTR is jargon for how much of an extra dollar earned is lost to income tax, withdrawal of benefits, and in this case HELP repayments. EMTRs are a big issue in Australia’s welfare state, which makes widespread use of means tests – of which the HELP repayment thresholds are a version.

Read More »