The housing section of the RBA’s report last week on international students and the economy had higher education media dismissing the contribution of students to rent increases as a ‘furphy’. I agree that international students are at most one factor amongst many in post-COVID accommodation market problems. That said, the RBA may understate the scale of international education’s contribution to rental demand.

Student Experience Survey results

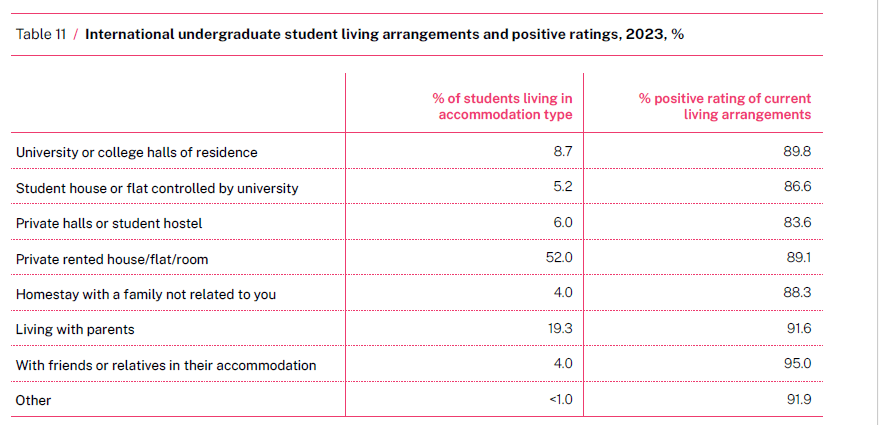

The RBA used the Student Experience Survey to try to work out the proportion of students in the private rental market where they compete with others for accommodation. The question the SES asks is below.

The RBA’s conclusion that about half of international students are in the private rental market is based on the result below, which is for undergraduates. Taking a broad definition of undergraduate that was about 40% of international students in 2023. But assuming it is broadly representative, there is still one number that I have persistently struggled to understand in this survey, which is the high percentage of international students who say they live with their parents – 19% in 2023. Can that be right?

Accounting for living with parents

One obvious reason why the parent numbers are higher than we might expect is that, although the SES is aimed at onshore students, the ‘current’ in the question captures students who are, perhaps temporarily, located offshore. Assuming most of them are with their parents, in 2023 that accounts for 3% of the 19% living with their parents.

But the remaining 16% still seems high, especially for university students. There is a student guardian visa for under 18s but this is otherwise only available in exceptional circumstances. The peak number of guardian visas in 2023 (for all levels of education) was 4,490 – not nearly enough to explain 16% of living arrangements.

Another explanation is that the students are children of temporary visa holders already living in Australia. There are thousands of teenage and early 20s secondary visa holders for people in Australia on temporary skilled work visas, but again I don’t think that this can explain the total.

The Census provides an alternative source of data on this matter, with the caveat that 2021 was obviously an unusual year for international students in Australia. Overall 3% of international students in 2021 lived with parents or grandparents, but this dropped to 1.5% for higher education students. By comparison, the 2021 SES reported that 16% of students lived with their parents. With many students stuck offshore in 2021 I can just about believe that figure, but I cannot easily believe the 19% in 2023.

Update: The 2024 QILT results support suspicions that the 2023 living with parents figures were wrong.

Other relatives

While the living with parents figure looks high, many major international student source countries also have large diasporas living in Australia. This makes it plausible that significant numbers of international students live with relatives who are already here and do not lead to new households being created (although the household may look for a larger place as a result).

In 2021, according to the Census 7% of international students lived with a sibling who may or may not also have been a student. Another 4% lived with other relatives – uncles, aunts, cousins etc – who again may or may not also have been students. Here we are starting to look at more significant numbers of additions to existing households, although it would require more in-depth research to calculate the totals.

The 2021 and 2023 SES results differ significantly on other relatives. The figure was 23% in 2021 but only 4% in 2023. Some of this may be locational issues in 2021 and/or being forced to save on rent due to labour market restrictions in 2021.

Overall rental status

In the 2021 Census, 15% of international students lived in dwellings classified as owned outright or owned with a mortage. This may not be a completely reliable figure. Often a ‘reference person’ fills out the census form for the whole household, with the ownership referring to their situation and not any rooms they have rented out to others, such as students.

In any case 15% is much lower than the RBA’s figure, which assumes that people living with relatives are not in renting households. Based on the Census many of them are renting, but the question I cannot answer is how many of these households existed prior to the student’s arrival, and how many are new households created due to additional student arrivals.

Total numbers of student-related visa holders

The RBA’s ‘back of the envelope calculation’ is that a 50,000 increase in the population pushes up rents by about 0.5%. With the caveats about limited knowledge of household situations, the increase in the number of student related visa holders in Australia since the COVID low point is just over 400,000 (counting only primary visa holders, assuming than partners and children on secondary student visas are in the same household). On the RBA’s formula with a 50% discount on numbers that would be a 2% increase in rent. With no discount it would be a 4% rent increase. With a 20% discount it would be 3.2%

Conclusion

I have been reluctant to engage in debates on student accommodation issues. In the broader housing debates there are many people passionately committed to their pet theories, and I don’t have the expertise to adjudicate.

In the international education aspect of that debate, there is an unverified assumption that no problem existed prior to COVID. I have long doubted the assumption that hundreds of thousands of international students can be put in already-stressed accommodation markets without any major consequences – for them or other people wanting to rent or buy.

Over the longer term the supply of accommodation is what matters. But that takes time, so I understand why governments reach for the few demand-side levers they can control.

Hi Andrew If my parents bought an apartment and I lived in it, would living with my parents be nearest correct answer? Best

Stephen

LikeLike

An email correspondent suggested something similar – than in the absence of a clearly correct description of their situation the student picked what they thought was the closest answer, such as the situation you describe.

In the Census there are people saying they own or own with mortgage across most of the family relationship categories.

LikeLike

Why the concern about international students and accommodation? Is this simply dog whistling racism? If we provide people with visas to live in Australia for years, they will need somewhere to live. It doesn’t make sense to take their money, then complain they are taking up accommodation, which they are paying for. As a former international student myself, is someone going to complain about me taking up accommodation? I studied overseas, online, without leaving Australia. So I took up accomodation in Australia while studying.If government wants to solve the housing shortage, this is very simple to do. Spend public money to build social housing for those most in need. Fix the current tax deductions which encourage building large houses with useless empty space. Resetting policy parameters to reducing the average home size by one quarter would solve the housing shortage, at no cost, with no need for extra builders, building materials or land.

LikeLike

Hi Andrew, your calculation on rental increase seems to be focused on total student visa holder and not increase student in a given year. The suggestion that no discount causes a 4% increase in rent, seems to suggest a baseline of no international student under a normal economy.

LikeLike

Annualised figures from end of September each year 2021-22 = 113,777, 2022-23 = 259,438, 2023-24 = 37,927.

I was just basing the analysis on increases from the low point in 2021.

LikeLike