The 2024 Graduate Outcomes Survey finally came out this week. As recently as 2021 the GOS came out in the year it covered, not September the following year. The government’s inability/refusal to release data in a timely way means that we need alternative sources of information for sector-relevant trends. This post reports on the GOS and brings in job advertisement and ABS data.

2024 graduate employment results

What I found in alternative sources for 2024 graduate outcomes made me concerned. The ABS labour force survey showed a downward trend in employment for young graduates. If this was right, was it cyclical or something more structural, such as AI reducing entry-level employment? A couple of recent US studies, one specifically looking at recent graduates, suggested an AI impact.

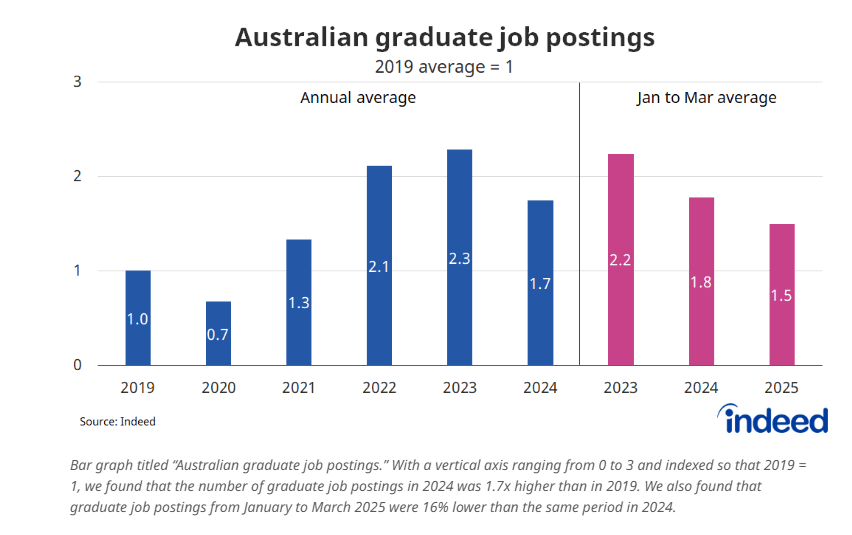

In May 2025, Callam Pickering looked at online job ads for graduates. He found that ads mentioning graduates declined in 2024 compared to 2023 – although they still exceeded 2019 levels. At least to March, ads for graduates in 2025 were tracking below the same months in 2024.

Fewer job ads targeting graduates cannot be good news, but I am not sure how important these are to the overall graduate labour market. There would be jobs typically taken by recent graduates that are not part of graduate programs or exclusively marketed to graduates. As work-integrated learning becomes more common, are firms increasingly hiring people they already know, recruiting graduates but not using advertising to find them? In analysis based on the 2023 GOS, but only graduates from institutions that had paid extra for WIL questions, 19% of people with new undergraduate qualifications said they had secured employment with a WIL employer and another 10% through a network contact made during their WIL experience.

Whatever the predictive value of job ads mentioning graduates, the GOS shows a parallel deterioration in short-term graduate outcomes between 2023 and 2024 (chart below). Of the 2024 graduates looking for full-time work, 26% had not found it four to six months after completion, up 5 percentage points on the 2023 result. This partly reverses the post-lockdown improvements observed in 2022 and 2023, but remains better than any other result between 2013 and 2021.

The longer-run data confirms a structural shift towards slower new graduate progression into FT work. If very low general unemployment in 2022 and 2023 can’t take us back to 2000s-levels of graduate FT employment then nothing will.

2024 outcomes for sub-groups of graduates

The GOS age categories aren’t ideal – 30 and under or over 30 – but as expected the younger group, with more people entering their first full-time job, was more significantly affected. Their yet-to-find full-time work rate was up 6 percentage points compared to 3 percentage points up for the over-30s (who are more likely to already have a FT job prior to graduation).

The American research suggests that IT and business jobs are most exposed to AI. Perhaps consistent with this, FT employment for IT graduates fell by 6.6 percentage points in 2024 compared to 2023, against 5 percentage points overall. Business graduate FT employment was down 6 percentage points. As these are not radically different from the overall trend I’ll put the AI theory in the ‘possible but more evidence needed’ category.

Later trends from ABS young graduate employment

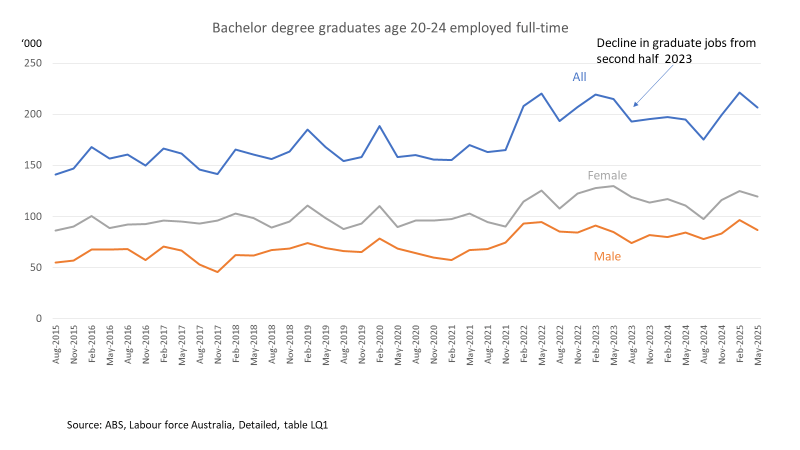

In the labour force survey I focused on the 20-24 age group, those mostly likely to be starting their first full-time employment. In the quarterly ABS data with qualification levels, problems with graduate full-time employment start in August 2023. These appear worse for female graduates, or at least they fell from a greater height than males. In the GOS, however, women do better than men (second chart below, but of all recent graduates with an undergraduate qualification, not just those aged 20-24 years). I examine the credibility of ABS survey gender differences later in the post.

FT bachelor graduate employment numbers started improving again in the second half of 2024, a more positive sign for graduates entering the workforce in late 2024 or early 2025.

Professional and managerial employment

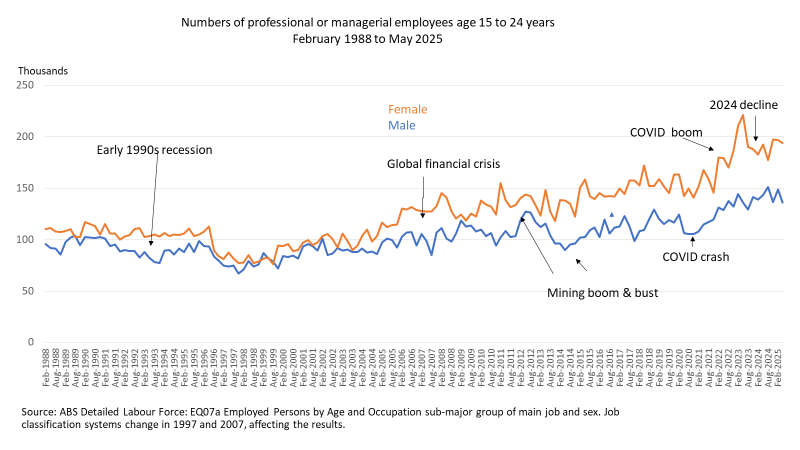

Switching to occupational categories gives us a longer time series and brings in a proxy for job quality, professional and managerial employment (for 15-24 year olds). However these employees may or may not be graduates. This time series shows the decline starting in May 2023, reaching its low point in February 2024, before a partial recovery.

Several things interest me with this chart. First, professional and managerial workforce feminisation, reflecting undergraduate enrolments and employment growth in female-dominated professional occupations.

Second, male employment was more affected in the early 1990s recession, the mining boom going bust and the COVID crash – probably reflecting predominately male occupations more exposed to the business cycle than predominantly female jobs in education, health and care occupations.

Third, if we believe the recent data for women the 2024 decline differed from previous negative trends in being driven by a spike then a major fall in female employment.

I’ve looked at other data sources to reality-test ABS trends in young female employment. In the 25-34 years age group, professional and managerial employment figures revealed nothing unusual in the female numbers over the relevant time periods. For 20-29 year olds in the industry payroll data, focusing on female dominated industries, health care showed increasing numbers while education showed annual drops over summer but otherwise looked flat over the relevant time period. For internet-advertised job vacancies there was a drop in health and education vacancies, but also in male-dominated ICT and engineering jobs and more evenly gender balanced legal and business jobs. This looks more like the general trend that led to worse outcomes in the 2024 GOS than anything specific to female employment prospects.

On balance I think the large spike in female employment between November 2022 and February 2023 was, in part, caused by an over-representation in the ABS sample of young women with good employment outcomes. People remain in the labour force survey for 8 months, with one-eighth rotated out each month. As this anomalous group left the sample we see results that continue previous trends more smoothly.

Conclusion

The GOS, ABS qualification and occupation data for people aged 24 and under, and job advertisement data are all consistent with a decline in graduate outcomes between 2023 and 2024.

The ABS data suggests that 2025 GOS results might be slightly better than those in 2024, but the graduate-specific job advertisement data points in the other direction.

Let’s hope we don’t have to wait until September 2026 to find out how graduates responding to the 2025 GOS survey were faring in the job market in early 2025.