As announced last year, the government plans to crack down on so-called ‘over-enrolments’ – enrolling additional students on a student-contribution only basis once all a university’s Commonwealth Grant Scheme allocation has been used.

When a proposed new funding system is in place, from 2027, student contribution-only places will only be possible in a buffer zone above a university’s Australian Tertiary Education Commission allocation. 2% and 5% buffers have both been suggested. Currently over-enrolled universities will receive some additional funding to bring over-enrolments within their official allocation of places. However, this will not in all cases reduce over-enrolments to the permitted range. Significantly over-enrolled universities need to moderate student intakes in 2026 to bring their medium-term enrolments down.

Not many current Department of Education staff were there the last time a minister thought reducing over-enrolments might be a good idea. The story is worth telling.

Brendan Nelson and over-enrolment

From November 2001 to January 2006 the education minister was Brendan Nelson, a Liberal. Nelson was worried about the quality implications of significant over-enrolments. The first reference I can find to Nelson’s concern is in a media release from December 2001, a month into his term.

In April 2002, the government released the first of Nelson’s ‘Crossroads’ discussion papers. It noted that “between 1996 and 2001, undergraduate over-enrolment increased from 11,417 to 30,658 equivalent full-time student units.” It suggested that “marginal payments for over-enrolment could either be discontinued or limited to say a maximum of 5 per cent to protect quality”.

At the time there was another aspect of the supply of undergraduate places, which I had forgotten about until doing some research for this post. In the good old days the government published annual reports on its higher education policies. In a report released in March 2002, the month before the first Crossroads paper, the government expressed concern about undergraduates occupying 5,400 places in 2001 the government thought should be for postgraduates, especially in teaching, nursing and other community service courses. “It expects most institutions to fill these places with postgraduate coursework students by 2004.”

So over-enrolments aside, undergraduate opportunities were already under threat for 2003 and 2004.

In May 2003 the government announced its higher education reforms, with a 2% over-enrolment cap. After sector resistance Nelson compromised on a 5% cap in the bill that was introduced into Parliament in September 2003. (In a case of history nearly repeating itself, the current government started with a 0% cap before changing its mind to the 2-5% range after sector complaints.)

The goverment did provide 2,560 additional fully-funded undergraduates places for 2003. But this was way below over-enrolments. Over-enrolled universities knew they must bring their undergraduate numbers down to or below their allocation + 5% by 2005.

The enrolment consequences

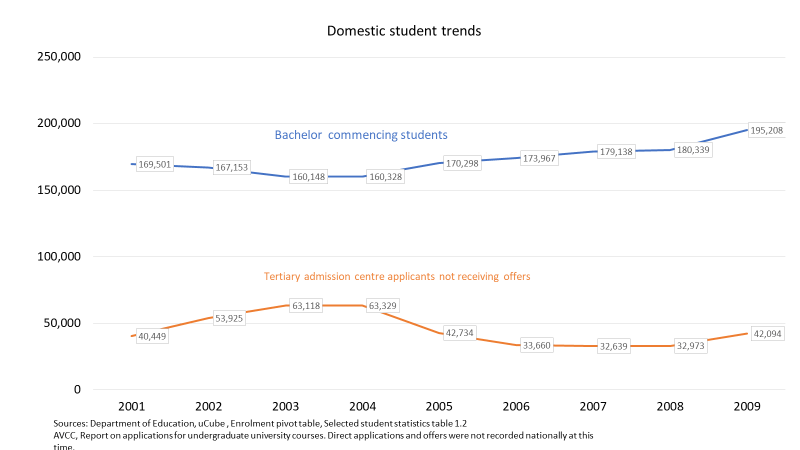

Predictably, these policies led to fewer commencing bachelor-degree enrolments – about 7,000 or 4% fewer in 2003 than in 2002, with the numbers stable in 2004 before increasing again. We can see from applications data that unmet demand increased, confirming a supply-driven cause of falling student numbers.

The participation consequences

Fortunately this contraction occurred in a period of flat school leaver demographics (chart below), which reduced the participation rate impact of Nelson’s policy.

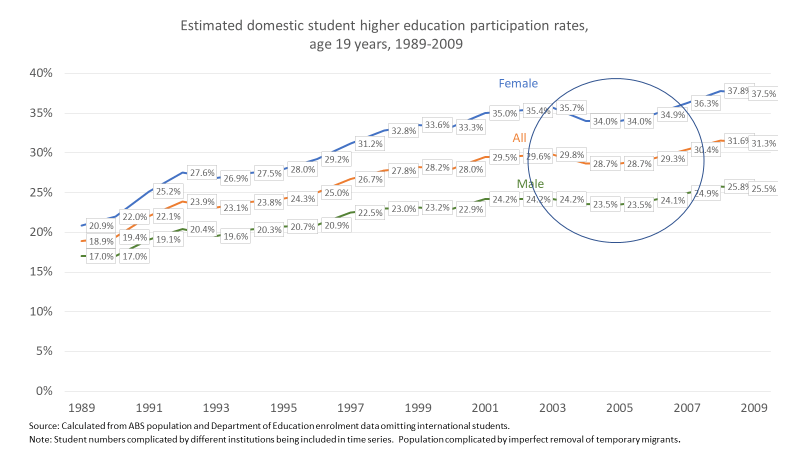

Nevertheless we can see in my participation rate at age 19 time series that rates dipped in 2004 and 2005, before increasing again. The drop was larger for female than male students. Many of the new fully-funded places were allocated to ICT, maths and science, with ICT especially being a male dominated field.

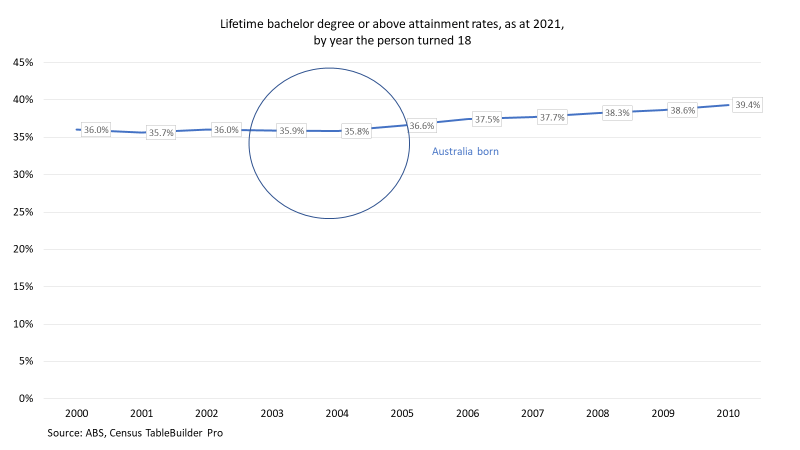

I also have a Census-based measure of lifetime attainment of a bachelor degree or above by the year a person turned 18. This incorporates all qualifications achieved up to the Census year (2021 in this case), but helps track the birth cohort effect of policies.

The lifetime attainment drop for the Australia born people who turned 18 in 2003 and 2004 is very small, but attainment growth stalls for a couple of years in a time series that otherwise increases in most years.

Restricting analysis to the Australia born is not ideal, as migrants typically have a greater interest in higher education. The longer your family connection to Australia the less likely you are to go to university. For citizens the drop in attainment for those who turned 18 in 2003 or 2004 compared to in 2002 is one percentage point larger than for the Australia born. However the complicating influences of the educational profile of migrants on arrival, or acquiring Australian degrees as fee-paying international students, make it harder to prove a domestic policy effect.

Nevertheless, despite later catch-up study, suppressing enrolments for even a short period can cause long-lasting effects on attainment rates.

Differences between the early 2000s and now

The early 2000s, as noted, were a period of flat Year 12 numbers. In the mid-2020s Year 12 numbers are increasing. For the chart below I used 2024 Year 10 and 11 enrolments to estimate Year 12 enrolments for 2025 and 2026, which suggest higher numbers than in 2024. While Year 12 enrolment has become less predictive of university entry, it seems likely that more school leavers will seek a university place in 2026 and 2027 than in 2024 or 2025. Stable commencing numbers could still lead to lower participation rates.

On the positive side for meeting school leaver demand, at least in 2026 we will not simultaneously have the government moving student load from undergraduate to postgraduate and reducing over-enrolments. In 2026 universities wanting to protect undergraduate opportunities can move CSPs from postgraduate to undergraduate. Universities can offer domestic full-fee postgraduate places to maintain total enrolments (if there is sufficient demand at the full-fee price point).

In the early 2000s, public universities could offer full-fee domestic undergraduate places, similarly at a price disadvantage and back then without FEE-HELP loans. The historical data shows an increase of about 1,800 EFTSL on this basis between 2002 and 2004, partially offsetting the effects of fewer CSPs. This option does not exist in the mid-2020s. But there is now a much larger private higher education sector operating outside the CSP system using FEE-HELP loans. Universities experiencing excess demand can divert some of it to pathway colleges, saving commencing EFTSL before taking the students into second year. These colleges are more expensive than CSPs, so price resistance will make this a partial solution.

Finally, there is the issue of policy intent. In the early 2000s Nelson was primarily concerned about the quality implications of over-enrolments. In the mid-2020s the policy motivation is more the government’s protectionism, with the minister’s objection to what he calls a ‘hunger games’ approach, under which some universities grow at the enrolment expense of others.

To be clear, I don’t believe the current minister wants to reduce enrolments – his goal is increased enrolments and participation. But a system that puts the interests of universities ahead of the interests of students risks these goals. Prospective students may reject offers from the university the government thinks they should attend. The less flexible student place allocation becomes the higher the risk that actual enrolments fall below the system’s theoretical capacity.

Why is the Australian Government allocating numbers of student places at individual universities? What does it matter which institution the student studies at, as they are all required to meet the same standard? If the goal is to meet particular skill needs, then this should be by program, at any university. Having more students at a university doesn’t reduce the quality of education.

What is wrong with competition between universities for students? Those universities which are not offering what students want should go out of business.

LikeLike