Update 28/11/2025: Last night the Senate accepted Coalition amendments that exempt higher education providers and TAFEs from the requirement to offer courses to domestic students for two years before being eligible to offer courses to international students. So effectively the provision discussed in this post applies only to non-TAFE registered training organisations. As I noted in the original post, offering courses to domestic students for two years is much easier for RTOs than higher education providers. Large numbers of RTOs have already met the requirement and could move into international education.

While this is good news, enrolment caps the government will try again to legislate next year could prove another insurmountable obstacle to education providers of any kind entering the international market.

————————————————————————————————-

Last week Claire Field published an interesting overview of 15 new higher education providers since January 2024. But growth of this kind would become very difficult if the government’s ESOS amendment bill passes unamended. It would limit registration of new providers offering courses to international students. This post examines whether the proposed restriction would, in practice, be a de facto ban on new higher education providers.

Under the ESOS amendment bill providers could not offer courses to international students without first delivering courses to domestic students, but providers are generally not competitive in the domestic market without offering FEE-HELP loans. But to get access to FEE-HELP, providers must demonstrate experience in delivering higher education – in practice usually by teaching the international students the ESOS bill would stop them recruiting.

Legislative references are to ESOS Act 2000 section numbers, as they are or would be if the amendment bill passes unchanged.

The proposed changes

The ESOS amendment bill would give the minister the power to suspend, for up to 12 months, applications and processing of applications for course and provider registration: sections 14C to 14F.

To be registered on CRICOS to offer courses to international students the provider must have delivered courses for consecutive study periods over at least two years to domestic students in Australia: section 11(2).

This post focuses on the section 11(2) change by looking at how providers have entered the international and domestic markets in recent years.

How reliant are new higher education providers on CRICOS registration?

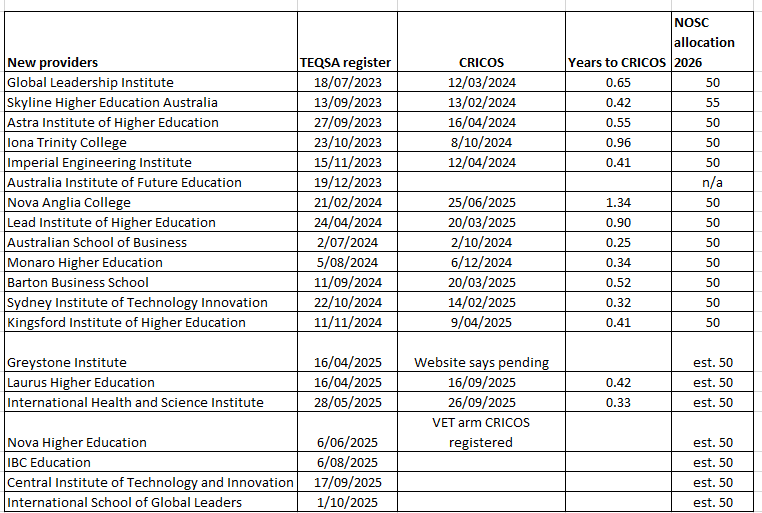

To explore new provider reliance on international students I examined new additions to the TEQSA register since the last edition of my Mapping Australian higher education publication, which takes us back to mid-2023 when my updating concluded. These are listed in the table below.

Of the 20 additional providers, 14 are CRICOS registered, 1 says CRICOS registration is pending and 1 has an already CRICOS registered VET arm. Three more are recently TEQSA approved, two with ‘international’ in their registered names and the other offering IT courses. I expect that these three have CRICOS applications in the system. The one new provider with no apparent interest in international students is the Australia Institute of Future Education, which is aimed at academics.

Of the 14 CRICOS-registered providers all but one were registered in less than a year after TEQSA approved them as providers. CRICOS registration looks like an important part of the business model for the vast majority. Making new providers wait at least two years for CRICOS registration – presuming they can attract domestic students – would be a significant business deterrent.

On top of the two-year constraint is the attempt to cap ‘new overseas student commencements’ (NOSC), with new providers hit hard – a minimum level of only 10 students in 2025 and 50 in 2026, which all but one new provider has been given. The NOSC is not, however, enforceable beyond slow visa processing and the private higher education industry has ignored it – awarded 31,000 places for 2025, while as of last week having moved 46,600 NOSCs through to getting their student visa. The government is going to try again for enforceable caps next year as part of its Australian Tertiary Education Commission legislation.

Domestic students

All TEQSA-approved providers can enrol domestic students, but tracking new provider reliance on domestic students is not straightforward. Domestic students are not automatically included in the Department of Education student statistical data. For inclusion the provider must be registered for the FEE-HELP income contingent loan, which none on the above list are for a reason that will soon become apparent.

TEQSA used to provide aggregate system-level enrolment data in an annual statistical report, but unfortunately that was discontinued. The last published figures are from 2017. By comparing these to the 2017 Departmental statistics there were 4,902 domestic EFTSL outside the HELP provider group, or 0.65% of all domestic EFTSL.

I believe that most domestic students outside the Department’s statistics are in specialist government, industry or professional organisation non-university higher education providers – such as the Australian Institute of Police Management, Bureau of Meteorology Training Centre, or the Governance Institute of Australia – where employers typically pay the fees or most students are affluent enough not to need FEE-HELP.*

In other markets, not offering FEE-HELP puts providers at a significant competitive disadvantage as students must pay their fees upfront, when they could take out an income-contingent loan at another institution.

Provider access to FEE-HELP

FEE-HELP is an unusual higher education funding program. It is rules-driven rather than based on history and politics. Apart from Notre Dame, every university with access to the Commonwealth Grant Scheme and HELP via Table A of the Higher Education Support Act 2003 was already publicly funded in the 1980s. By contrast, so long as the provider meets stated criteria its students can access FEE-HELP. More than 100 non-university higher education providers and university colleges offer it.

In 2017, however, as part of its response to the VET FEE-HELP scandal, the Coalition amended the Higher Education Support Act 2003 to alter the FEE-HELP approval process. Since then to approve a provider for FEE-HELP the minister has to be satisfied that ‘the body has sufficient experience in the provision of higher education’: now section 16-25(fb) HESA 2003. For the purpose of assessing experience the minister may have regard to ‘whether the body has been a registered higher education provider for 3 or more years: emphasis added, now section 16-25(2A)(a) HESA 2003.

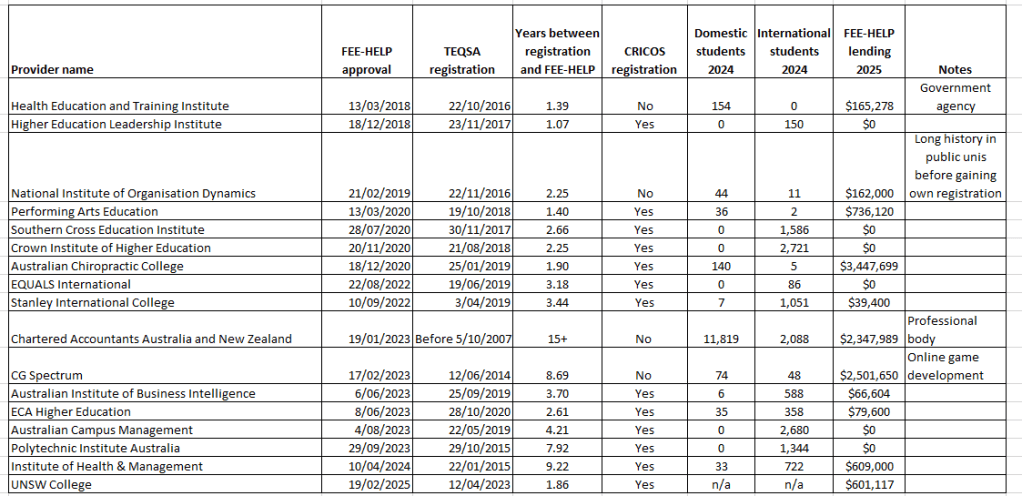

The table below lists the 17 NUHEPs approved for FEE-HELP from 2018.** Until 2022 the 3-year requirement was not applied. Since 2022, most FEE-HELP approvals occurred more than 3 years after initial TEQSA registration. From the chart, a minimum two years may have been required except for UNSW College, which as a UNSW spin-off is only technically a new provider. The Chartered Accountants are a longstanding provider that would have been eligible for FEE-HELP long ago. For the others, I don’t know to what extent the time between TEQSA registration and FEE-HELP approval reflects regulatory factors or business decisions. The fact that 6 of 17 providers in the table report no domestic students in 2024 and no FEE-HELP lending for 2025 confirms that their business model is primarily based on international students.

Only one of the 17 new FEE-HELP providers had no international students in 2024, but it is the training arm of the NSW health department, with no commercial need for the international market. Another 5 of the 17 new FEE-HELP providers enrolled both domestic and international students but, based on enrolments, primarily served the domestic market. Three providers reported international students despite not being CRICOS registered.*** Two of the 16 providers with international students reported very low numbers, but otherwise international education looks to be part of the business model for most providers getting access to FEE-HELP. This is consistent with my analysis of newly registered TEQSA providers.

A de facto ban on new providers?

Some providers can operate without international students or FEE-HELP. But for organisations trying to compete in non-niche markets things will be difficult if the ESOS amendment bill passes:

- Providers can’t offer courses to international students until they have enrolled domestic students for two years,

- But providers won’t be competitive in the domestic market unless they offer FEE-HELP, which in practice they can’t get until they have enrolled international students for at least two years or can otherwise prove ‘sufficient experience’ in delivering higher education.

Routes around the 2-year ESOS restriction

The interaction of FEE-HELP and ESOS changes would make things difficult for new higher education providers. But the two years of domestic provision rule prior to CRICOS registration appears to be sector/AQF level neutral. The ESOS bill explanatory memorandum states (p. 50) that ‘it is not intended that a provider be limited to only applying for registration of the same course that was delivered to students other than overseas students’, although it does not directly address the sector/AQF level issue.

If so, two years of delivering vocational education courses to domestic students may be sufficient to make the leap to CRICOS registration for higher education courses. After two to three years of delivering to international students the provider will have sufficient experience to qualify for FEE-HELP.

We already have several thousand vocational providers. VET Student Loans cover only a small proportion of the domestic vocational market. In the rest upfront fees are not a competitive disadvantage.

All this would be a convoluted process. But many providers have complex histories – starting in vocational or higher education and then expanding to the other, or offering non-credentialed training and later moving into formal AQF qualifications. And the government supports blurring the sectors through its ‘tertiary harmonisation’ policy.

The block on this higher education provider creation process may be enforceable NOSC caps on international students keeping enrolments below financially viable levels.

The future

Higher education is at a policy turning point. Partly through a series of ad hoc responses to specific issues, partly due to the current government’s general preference for bureaucracy over markets, we are moving from a system that allowed new entrants and enabled competition between providers to a system micromanaged from Canberra.

The attempt to create an enforceable cap, through the ATEC legislation next year, will be a major political battle not just for the future of international education but for an open, rather than a state-controlled, higher education system.

If the government is successful, the whole sector will look like Table A of HESA 2003 – a list of institutions largely frozen in time, lobbying for their share of government-controlled student places.

*Based on the Chartered Accountants enrolments after accessing FEE-HELP in 2023, seen in the second table, in 2017 they were likely to have enrolled a significant share of domestic students outside the Department’s enrolment statistics. I am unsure when the Chartered Accountants became a registered higher education provider. The earliest reference I can find is a list I created dated 5 October 2007, from the pre-TEQSA state-based registration system.

**The legislative instruments used for FEE-HELP approval have used varying titles over time. I think this list is complete but there may be omissions. I have not recorded the date of first CRICOS approval as the TEQSA regulatory decisions list for each provider does not necessarily provide it for older institutions. International student enrolments are not directly reported, the figure given is total enrolments minus domestic enrolments. Where the Department records ‘<5’ I substituted zero in the calculation.

***Recording international student enrolments despite not being CRICOS registered is possible if the students are offshore, studying online or at a partner institution or offshore campus, but I have not investigated further.

The mindset of education policy makers, and many in universities, seems to be that teaching the international students is just a byproduct of teaching domestic ones. You design and deliver programs for local students and then fill up empty seats with foreign students. This shows a lack of understanding of education as a practice and as a product.

I suggest changing this mindset to providing education to students in an international environment, addressing the individual needs of each student.

LikeLike