Last year the Parliament passed legislation making Commonwealth supported places demand driven for Indigenous students enrolled in medical courses. It sounded good, we need more Indigenous doctors. But as I pointed out, the policy as legislated risked reducing non-Indigenous medical student enrolments without increasing Indigenous medical students enrolments.

The 2026 funding agreements reveal that the Department of Education has been quite inventive in finding a workaround to prevent this perverse outcome. The price, however, is yet more complexity in higher education policy.

The problem

A demand driven funding policy for Indigenous medical students assumes that fixed total funding holds Indigenous enrolments down. Student places are indeed unusually restricted in medicine. Medicine is the only ‘designated’ course, meaning that the government sets a specific number of student places. While designation does not prohibit over-enrolments (i.e. student contribution only places), medicine also has a completions cap. A standard funding agreement clause specifies that a university must not change its medical enrolments in ways that will change annual completions from the capped level.

While medical student numbers are restricted it is not clear that this prevents increased Indigenous enrolments. As I argued in my original post, universities already try hard to recruit Indigenous medical students, with special entry schemes and quotas in some cases. On the available data (below) these schemes are delivering Indigenous enrolments, a source of pride for the medical deans association. 3% of domestic medical students are Indigenous, compared to 2.3% of the overall domestic student population.

The main obstacle to further enrolment increases is unlikely to be funding. It is finding potential students who are not being set up to fail.

In moving to a demand driven funding system the transition period has risks. New demand driven systems are principally funded by reclassifying places. In this case, taking Indigenous students in medical CSPs out of each university’s designated medical places and putting them in the new demand driven program.

If the future number of Indigenous medical students falls short of the number removed from the allocated number, then the total number of medical places will decline. Under the normal rules, universities cannot just recruit another non-Indigenous student from among the two-thirds of medical applicants who did not receive an offer. If they did that, they would exceed their number of designated places and risk exceeding their completions cap.

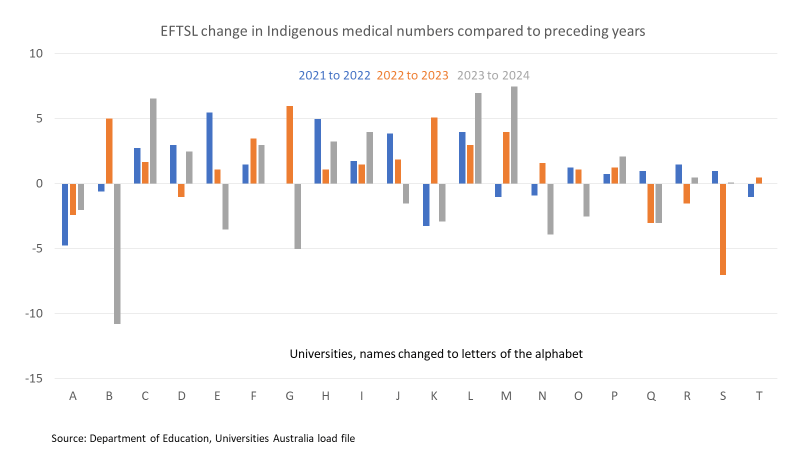

This is not a hypothetical concern. Even when aggregate Indigenous medical numbers increase, individual institutions experience decreases. The chart below shows year-to-year fluctuations in Indigenous medical EFTSL by anonymised university. 14 of the 20 universities had at least one year-on-year decline between 2022 and 2024.

The solution

The Department recognised the problem and devised an inventive funding agreement fix. The example below comes from the Monash University funding agreement, with equivalent provisions for other universities with medical schools.

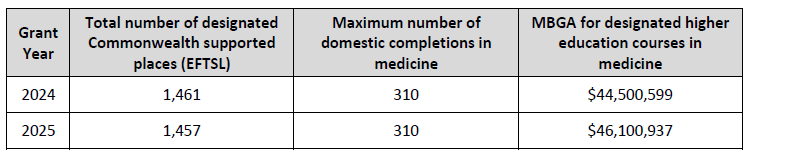

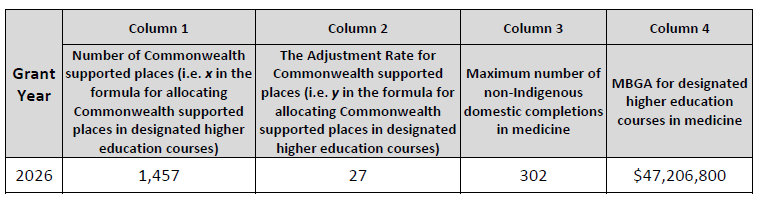

In 2025 Monash was allocated 1,457 medical CSPs. For 2026 the government did not want Monash falling below this base number, which reappears in column 1 of the 2026 allocation. Monash had 27 Indigenous medical EFTSL in 2024 (the last ‘verified’ data).

The new designated number of non-Indigenous places is 1,457 minus the lesser of 27 and actual Indigenous EFTSL for 2026.

So if the actual number of Indigenous EFTSL in 2026 is 27 or higher, the designated number of places for non-Indigenous medical students will be 1,430.

But if the number of Indigenous EFTSL in 2026 falls to 20, the designated number for non-Indigenous medical student places will adjust up to 1,437.

Another complexity

The column 2 adjustment was ‘discounted for providers where the proportion of Indigenous students exceeded population parity for 15-34 year olds (as derived from the 2021 Census and reported by the Australian Bureau of Statistics).’ That figure is 4.2% if we use the entire population or 5.3% if we use Australian citizens.

Charles Sturt, Newcastle, and Western Sydney all exceeded the 5.3% Indigenous medical threshold enrolment share in 2024, while 5.2% of Flinders medical students were Indigenous. All these institutions receive a column 2 adjustment below their Indigenous medical enrolments in 2024.

I am not sure of the rationale for this policy, but it will make it easier for these institutions to increase their total medical enrolments.

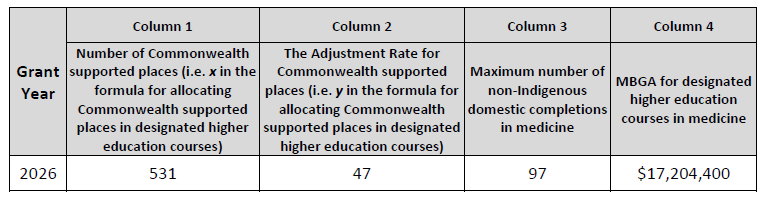

Take as an example the University of Newcastle, 2026 funding agreement extract below.

In 2024, Newcastle’s medical school delivered 52 Indigenous EFTSL.

If that was applied in the standard formula, the non-Indigenous designated medical places cap would be 479 (531-52). Any 2026 Indigenous EFTSL number above 52 would add to total medical places.

With the ‘discount’, a column 2 number of 47 rather than 52, the lowest non-Indigenous cap is 484 places (531-47), 5 more than would have been the case if Newcastle medicine did not already have a high Indigenous enrolment share.

The completions adjustment

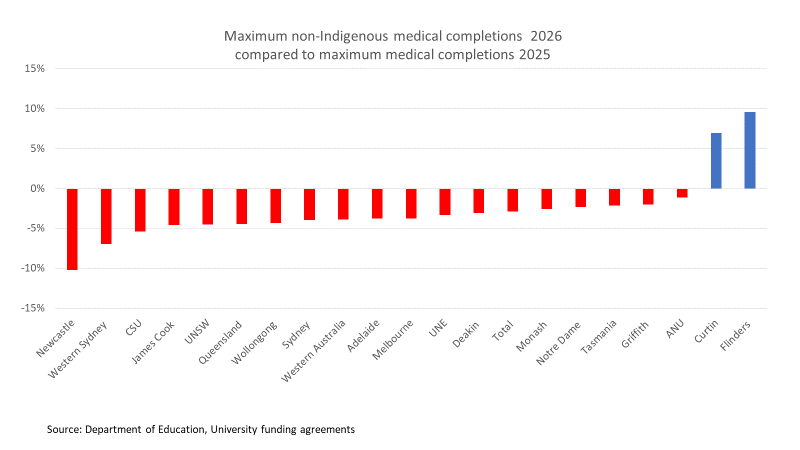

The annual completions cap is of greater legal force than the designation of places. Breaching it could lead to a loss of grant money. The chart below shows changes in maximum completions between 2025 and 2026, with Indigenous completions removed to create a new non-Indigenous completions cap.

An analytical problem here is that I don’t know what other completions projections are flowing through to these numbers. Of course medical completions in 2026 reflect commencing enrolments years previously.

I interpret these revised completions caps as a signal of intent that the completions cap will not sabotage the demand driven Indigenous medical student places policy. Getting this right, with a non-Indigenous medical student allocation that can fluctuate less predictably than in the past, will create extra work for medical schools and government bureaucrats.

Projections of increased Indigenous demand

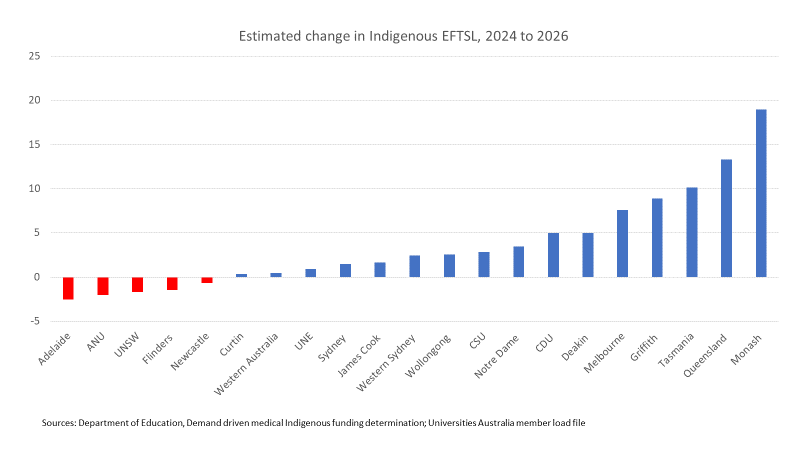

After all this bureaucratic effort it is a relief that the funding determinations imply a net gain of 77 Indigenous medical places in 2026 compared to 2024 (420/497). The places are not specifically mentioned – I calculated them on an estimated funding/medical Commonwealth contribution formula. This includes an estimated five Indigenous places for Charles Darwin University, new in the medical funding system in 2026.

Some, possibly much, of this will just be the flow through of increased enrolments in previous years (see first slide), but hopefully an increase in commencing places as well.

Conclusion

I have often been critical of the Department of Education’s use of funding agreements. While I remain a little concerned about the maximum non-Indigenous completions adjustment, overall the bureaucrats have done a good job of saving the politicians from themselves.

Decreasing the number of non-Indigenous medical students was not, of course, the Parliament’s intention in passing the bill for demand driven medical for places for Indigenous students. But its interaction with existing medical student policy could have produced that result. The five universities showing fewer estimated Indigenous medical places in 2026 than 2024 are examples of the dangers.

While negative outcomes have probably been averted, the workaround is complex. I believe extra demand from Indigenous applicants with good completion prospects could have been managed within the previous system. As the first slide showed, Indigenous medical enrolments have increased significantly over time without any special funding policies. With the Department’s fix, the main beneficiaries of this policy will be the non-Indigenous medical applicants who might otherwise have missed out, due to a priority being given to Indigenous applicants within a fixed pool of places.

Postscript – Is this the model for equity student ‘effectively demand driven funding’?

Like others in the sector, I have been baffled about how ‘effectively demand driven funding for equity students’ would work. Perhaps the Indigenous demand driven medical student system gives us the answer.

But an equity version of the medical hybrid capped/demand driven model would fit awkwardly with the minister’s goal of a more predictable, less competitive funding system.

The enrolment variations driven by the medical version of this model will be low double digit numbers in universities typically enrolling 20,000+ CSP EFTSL. This won’t affect university-level aggregates very much.

But add low SES and perhaps regional students to existing Indigenous bachelor degree demand driven funding and, for some universities, that’s a signifcant share of all CSP enrolments. Total enrolments could move from year-to-year in larger numbers than implied by the policy of keeping institution-level over-enrolments below 5%.