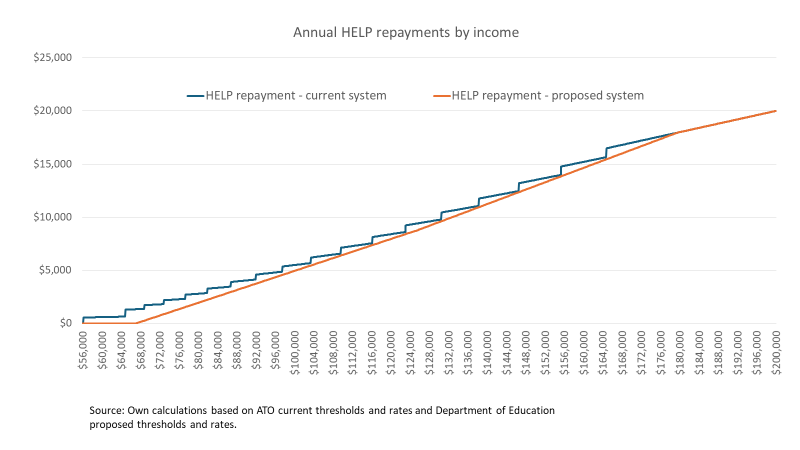

Last week I raised concerns about the new HELP repayment system increasing the number of HELP debtors who face very long repayment times or lifetimes of student debt.

The calculations in that post assumed that people maintained their relative income position through their careers – for example that someone who earned the median income at age 25 would still do so at age 35, 45 etc. We know, however, that relative income fluctuates. Family commitments drive movements in and out of full-time work. Careers go better or worse than expected.

Without solving the problems involved in estimating how these changes affect HELP repayments, this post outlines findings on graduate income mobility and labour force status changes.

Movements between income quintiles

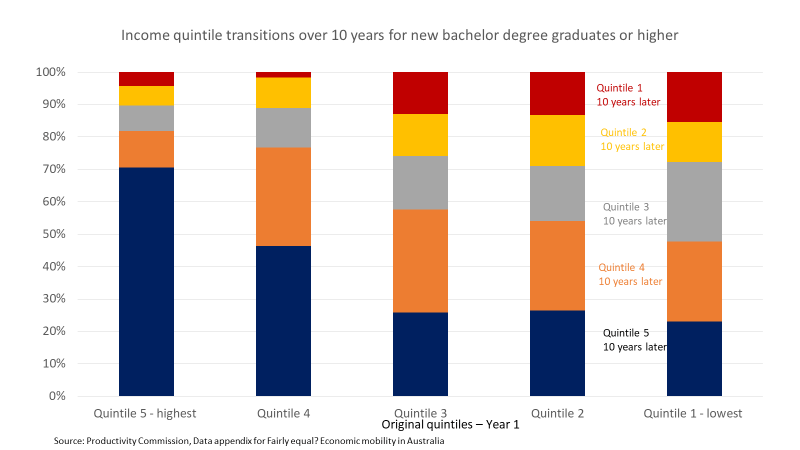

The chart below uses data from a Productivity Commission report on economic mobility. It shows changes in relative income, between five economic quintiles, over a decade since degree completion. The data source is HILDA.

Quintile 5, the highest, shows strong stability. More than 80% of graduates in quintile 5 were still there or in quintile 4 a decade later. The high starting point and following stability may be due to people already doing well in their careers acquiring postgraduate qualifications.

The other quintiles all show significant movement in relative income. Upward movement is expected as we know graduate incomes increase in the years after course completion. Almost half of graduates in the lowest quintile in year one are in the top two quintiles a decade later.

Bu there is also some stability at the lower end. In the two lowest quintiles, 1 and 2, over a quarter remain in those quintiles a decade later. In quintile 3 we see a similar share falling back to quintiles 1 and 2. While some of this is career stagnation, ten years out takes into the ages when women start leaving full-time work to meet family responsibilities.

Read More »