Today I start a new role as professor of higher education policy at Monash University. I am based at the Monash Business School on the Caulfield campus.

Author: Andrew Norton

Robert Menzies and the Murray review of universities

An earlier post looked at Robert Menzies and higher education, first as Opposition leader and then as Prime Minister, from 1945 to 1956. Despite important structural changes in the early 1950s, with the Commonwealth commencing grants to universities via the states and directly financing Commonwealth scholarships, the university sector remained small and financially weak.

In March 1956, Menzies agreed to a university policy review, what became the Murray report. This post draws on my chapter on the Murray report in The Menzies Ascendancy: Fortune, Stability, Progress 1954–1961, edited by Zachary Gorman and published last month.

The appointment of Keith Murray to review universities

By the time Menzies agreed to the review he had already decided that major changes to university policy were needed.

In his book The Measure of the Years, Menzies says that prior to his trip to England in 1956, where he first met Keith Murray in person, he told Treasurer Artie Fadden that he was initiating an enterprise that could not fail to be ‘vastly expensive’.

In December 1956 Murray was appointed as chairman. The four other members included CSIRO Chairman Ian Clunies-Ross, believed to be the subsequent report’s main author.

Read More »Robert Menzies and higher education, 1945 to 1956

I’m not an historian, but decided to accept a Robert Menzies Institute suggestion that I give a paper on the 1957 Murray report on universities for their 2023 conference on Menzies, which covered the years from 1954 to 1961. The book chapter version of that paper came out in December 2024.

As well as describing events surrounding the Murray report I tried some counter-factual history, in an attempt to understand the distinctive contribution of Menzies to Australian higher education policy. The post-WW2 period saw higher education expand in all the countries with which Australia compared itself. With or without Menzies, Australia’s pre-WW2 model of one impoverished, low-enrolment university in each capital city was not a plausible long-term system.

But what would have happened if Labor had remained in power after 1949, or won the close 1954 election? What would have happened if someone other than Menzies had led the Liberal Party (or the main non-Labor party, given Menzies’ role in creating the Liberal Party)?

This post looks at what happened up to 1956. A subsequent post examines the Murray report and its consequences.

Where are the young people who are not at university?

Earlier this month I wrote a post showing that higher education enrolments at age 19 years, and the domestic participation rate at age 19, were down in 2023 compared to 2022.

This post explores possible reasons for this downward trend.

The teenage job market

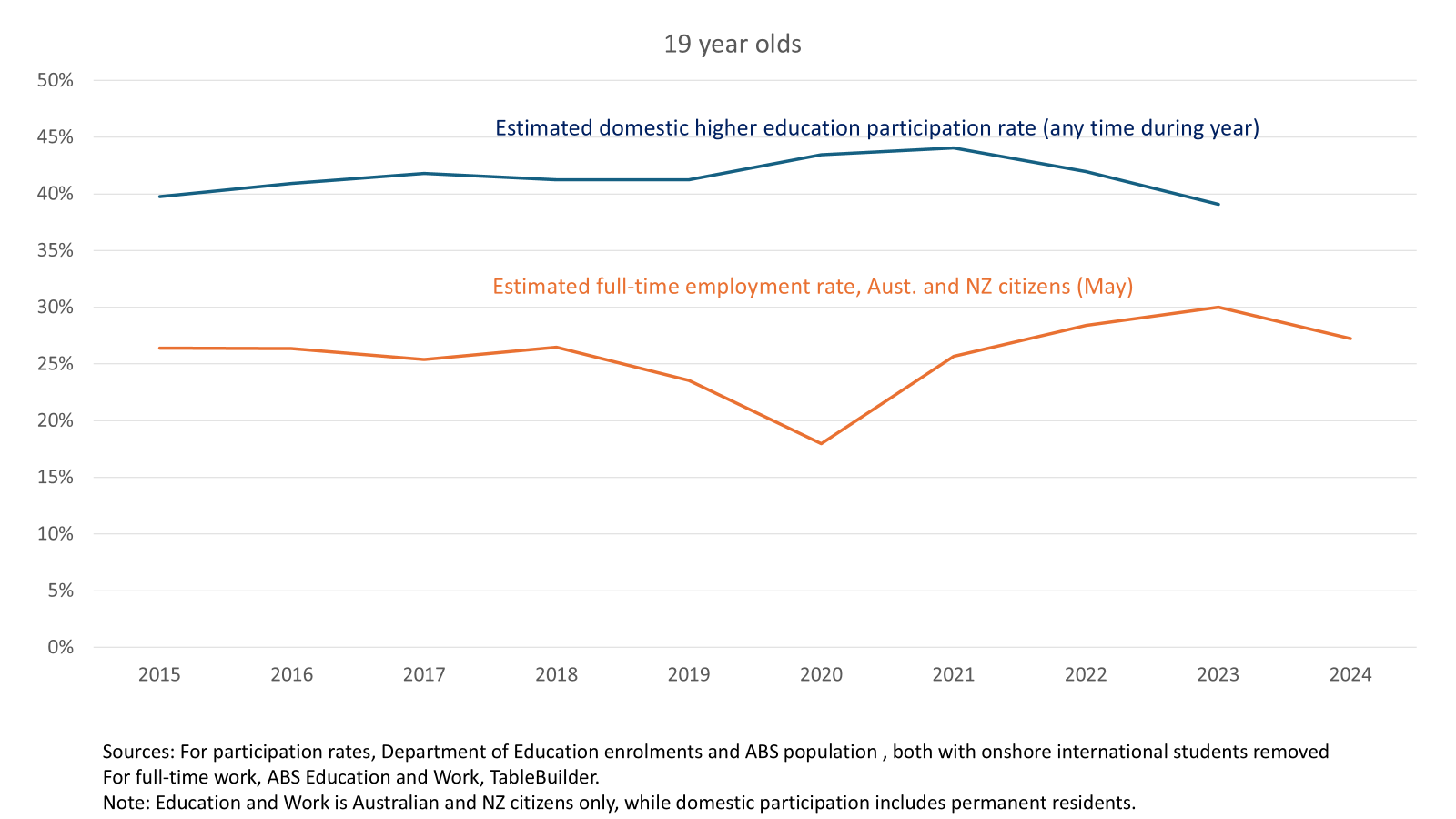

One explanation of declining enrolments at age 19 is higher education’s counter-cyclical relationship with the labour market. At the margins, some people prefer work to study, but study when work is not available. The higher education participation and full-time employment rates in the chart below match this theory. Higher education participation increased after COVID-related full-time job losses in 2020 and then decreased as job opportunities returned.

Education and Work TableBuilder supports analysis of smaller sub-groups than the standard ABS data releases, but with an increased risk of rogue results. Broader 15-19 year old statistics, however, confirm 2023 as a very strong year for full-time teenage employment. Both sources show that teenage full-time jobs grew strongly post-COVID and then softened in 2024, while remaining good compared to the 2010s.

Read More »The higher education participation rate at age 19 almost certainly fell in 2023 – but an exact rate cannot be calculated

Despite significant policy interest in higher education attainment rates, the preceding participation rates are rarely reported. The most readily available time series is in Mapping Australian higher education, at figure 5 of the 2023 edition. It reports the participation rate at age 19 years, the modal university student age. For the first time in decades, the Department of Education recorded a participation rate in their recent 2023 statistics release.

Unfortunately data issues mean participation figures are only estimates. This post discusses these data problems and compares participation rates using two different methodologies. Both point to participation in 2023 being lower than in all recent years.

Read More »Budget treatment of student debt policy announcements

One criticism of the weekend’s big proposed changes to student debt – a new repayment system and a 20% cut to student debt balances – is that they are ‘off budget’, concealing their true cost.

The Budget includes several different takes on the government’s annual finances, including fiscal balance, headline cash and underlying cash. The Budget papers also report the value of government assets, including student debt.

The ‘underlying cash balance’ is the most commonly used Commonwealth’s Budget metric. When the Treasurer boasts about the government’s fiscal performance he uses an underlying cash measure. Unfortunately from a ‘Budget honesty’ perspective underlying cash is the weakest measure of student loan costs and of the financial impact of proposed changes to student loan policies.

Read More »Big proposed changes to the HELP repayment system – a higher first income threshold & a marginal rate of repayment

Today the government announced big changes to the HELP repayment system. Its proposal involves several interconnected conceptual and practical considerations.

The first issue is where to set the first repayment threshold – how much should a HELP debtor earn before they start repaying? The government proposal is for a higher first threshold.

The second issue is annual repayment amounts, which affect the disposable income of debtors and how long it takes them to repay their debt. The government proposal is for most debtors to repay less HELP debt each year, increasing their annual disposable income but also their repayment time.

The third issue is the method of repayment. Should it be – as we have had since 1989 – a system which levies a % of all income when income reaches a threshold, or should we have a marginal rate system, which is a levy on income above the threshold (like the current income tax system). The government has decided on a marginal rate system.

All three issues intersect with the public finance element of HELP – the cash flow implications of the changes for the Commonwealth, and the costs in interest subsidies and bad debt. These will all be negative for the government.

In this post, I will look at the annual repayment implications for debtors, effective marginal rates of repayment, and make some initial comments about selling this reform to debtors and voters.

What the government proposes

The first threshold for repayment will go to $67,000, from $54,435 for 2024-25, and approximately $56,000 after CPI indexation for 2025-26 (I have assumed 3% indexation, which seems to be around what the government has estimated).

From this first threshold of $67,000 we will move to a marginal rate of repayment, at two levels – 15% from $67,000 to $124,999 and 17% from $125,000. These rates would replace the current whole-of-income rates ranging from 1% to 10%.

Read More »Mapping Australian higher education 2023 – October 2024 data update

Update 20/12/2025: More recent data here.

An updated version of Mapping Australian higher education is not on the horizon, but to extend the life of the 2023 version I have updated the data behind the charts and some tables. An Excel file with these and the two further updates mentioned below is here.

Further update 6/11/2024: The 2023 Student Experience Survey results have been released. Some question changes have broken the time series but the replacement question results are recorded.

Further update 12/11/2024: A careful reader has identified the missing higher education provider mentioned below and identified other errors in my institutes of higher education appendix. Hopefully the list is now correct and complete. This update also includes 2024 bachelor and above attainment data.

The original pdf with explanatory text is here.

Some noteworthy changes since its publication:

- We now know that domestic enrolments fell in both 2022 and 2023; enrolments last declined in 2004 (figure 3)

- International students – although no regular reader of this blog needs this pointed out – recovered strongly from the COVID period (figure 10)

- The source country skew of international students means that a top 15 source country does not necessarily send a lot of students, but for the first time an African country made it to the list, Kenya with 6,538 students in 2023 (figure 11) (and 7,330 onshore YTD July in 2024).

- Higher education student income support recipient numbers continued to fall, to 156,710 in mid-2023, the lowest figure since 2009 (figure 18). While since 2022 falling income support recipients is partly due to fewer students, except for a COVID spike the number has been in structural decline since 2017.

- Staff numbers recovered strongly in 2023 to be roughly what they were in March 2020 (figure 19)

- HELP repayments increased increased significantly, from $5.56 billion in respect of 2021-22 to $7.8 billion in respect of 2022-23 (figure 31B). Most of this was due to voluntary repayments increasing from $780 million to $2.9 billion, as debtors sought to evade high indexation (some of which will be refunded if the indexation reduction bill passes).

- Short-term graduate full-time employment rates improved, in 2023 reaching the best level since 2009 (figure 40)

- The number of higher education providers continued to increase, from 198 in mid-2023 to 211 in October 2024 (appendix A and appendix B).

The Department of Education’s failure to release the 2023 Finance or Student Experience Survey publications means that the update is not as full as I would like.

Visa processing and international student policy

Some universities and vocational education providers would prefer enrolment caps to ministerial direction 107, which consigned their offshore student visa applications to the end of the visa processing queue. 107 tells the Department of Home Affairs to give processing priority to applications for schools, postgraduate research, and higher education institutions with a low immigration risk rating.

The education minister has said that ministerial direction 107 will go if the caps bill passes.

While 107 should be repealed, as it unfairly penalises some student visa applicants and education providers, like Claire Field I think the sector over-rates the benefits that would follow. 107 is blamed for other things that happened around the same time that would not be affected if it went.

These other things include the resources Home Affairs allocates to student visa processing, changed practices in applying visa eligibility criteria, and new visa rules.

Student visa processing levels

From November 2022 to July 2023, Home Affairs put significant effort into clearing a student visa backlog. On my calculations, in those nine months they processed – counting both grants and rejections – 483,199 visa applications (primary visa holders only). That is 54% more than the equivalent number pre-COVID, between 2018 and 2019.

In the second half of 2023, shown in green in the chart below, monthly visa processing dropped back to levels that were similar to 2019. Ministerial direction 107 was announced in December 2023, but that was the fourth month of more normal pre-COVID visa processing volumes.

The National Student Ombudsman and bureaucratic overreach

With so much going on in higher education policy at the moment, the National Student Ombudsman legislation has not received much attention. But university submissions to the Ombudsman bill Senate inquiry raise important issues. I also put in a submission.

Academic judgement versus academic matters

University submissions make similar academic freedom objections to the bill as one of my blog posts on the National Student Ombudsman.

One issue is the scope of ‘exercise of academic judgement’, which is an ‘excluded action’ that the Ombudsman cannot investigate. The bill’s explanatory memorandum seeks to distinguish ‘academic judgement’ from ‘academic matters’, such as claims for special consideration and discipline for academic misconduct, which it thinks should be within the Ombudsman’s jurisdiction.

The QUT, Monash, University of Melbourne, ATN, Gof8, UA, UTS and UQ submissions all raise concerns about this aspect of the bill. As UQ says:

Read More »