I have an article in The Conversation this morning on why demand for undergraduate higher education has been weak in recent years. I looked at school leavers in this July 2025 post. This post expands on the issue of mature age demand.

Applications

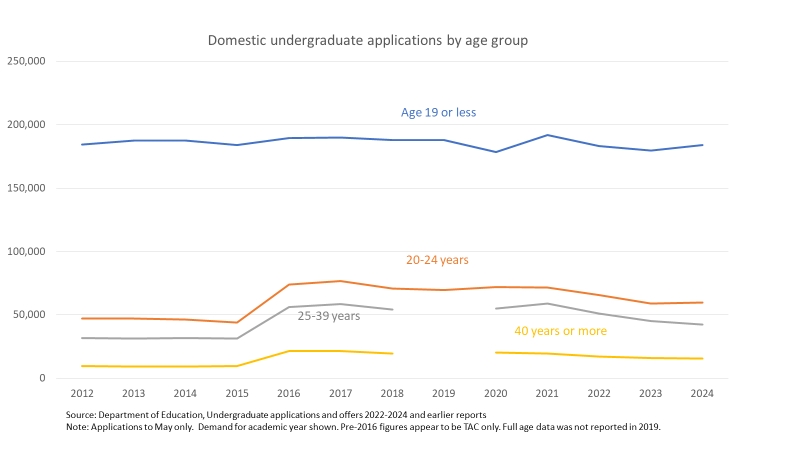

Demand from school leavers is soft but in 2024 was down only 3% on its 2017 peak. But demand from 20-24 year olds is down over the same period by 22% and for the 25 years + age group it is down by 27%. In absolute numbers, demand from school leavers fell by 6,057 applications compared to 44,545 fewer applications from mature age applicants.

Commencing enrolments

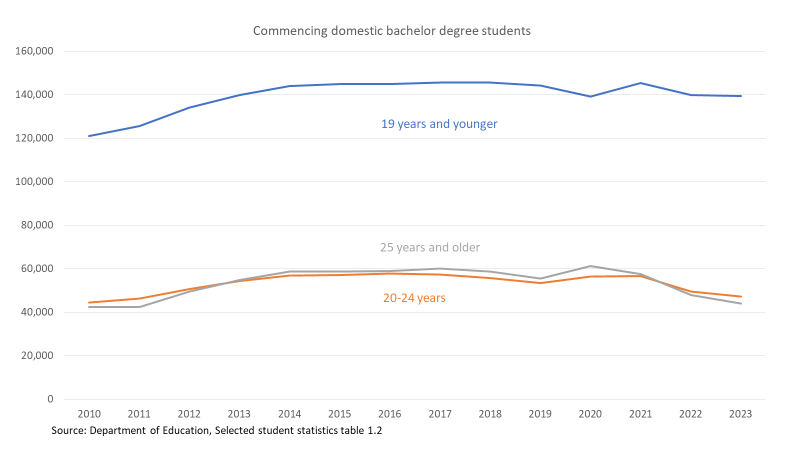

For commencing bachelor degree enrolments 2017 to 2023, unsurprisingly given the applications data, demand has also fallen by the most in the older demographics.

School leaver commencing enrolments are down 4% while the figures are 18% for the 20-24 years group and 27% for the 25+ group. Overall 6,216 fewer school leavers but 26,276 fewer mature age students.

Counter-cyclical enrolment patterns

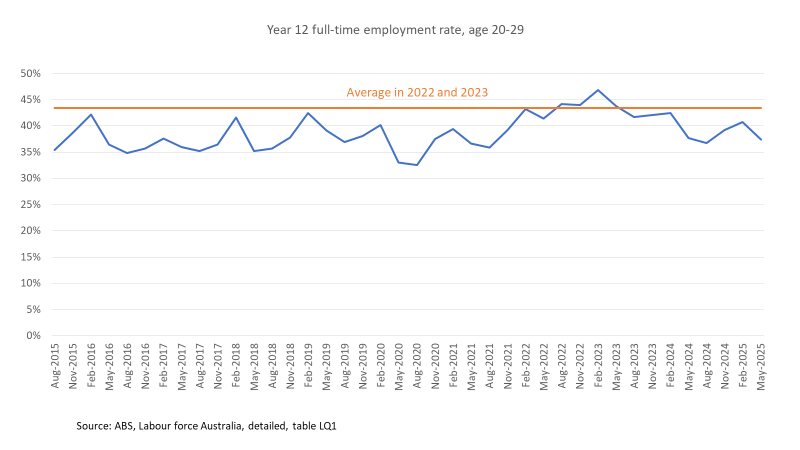

An applications/enrolment spike in the COVID lockdown years provided evidence for one side of the counter-cyclical theory of enrolments – that more people study when jobs are hard to find. Weak labour markets reduce the ‘opportunity cost’ of education, such as forgone work and wages.

Conversely strong labour markets increase the opportunity cost of study. On average this is especially so for older people, due to their wage premium from previous labour market experience. With a strong labour market since 2022 economic theory predicts that, all other things being equal, enrolments will decline.

In the chart below we can see full-time employment for 20-29 year olds who have completed Year 12 but have no degree was at its lowest level in 2020, in the 2015-2025 period for which we have education levels in the labour force survey. In the initial post-COVID lockdown period, however, we can see that it was much easier than it had been in the 2010s to get a full-time job with a Year 12 qualification only.

The 2020s has provided evidence in favour of the counter-cyclical theory of higher education enrolments.

But does a cyclical theory of enrolments fully explain declining mature-age commencements?

Read More »