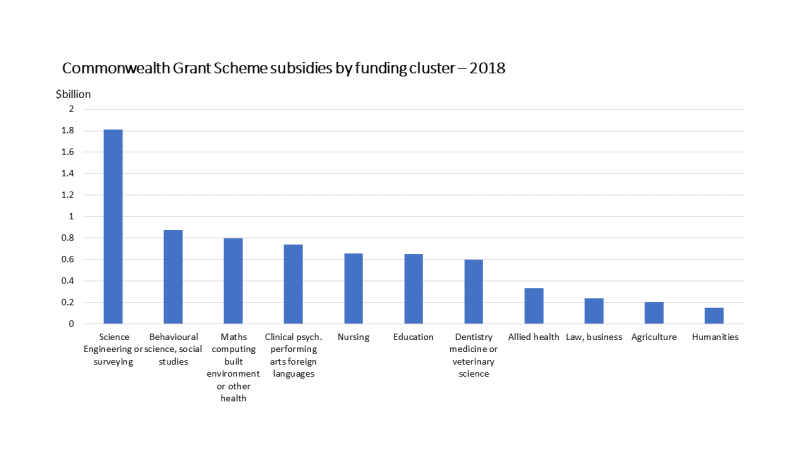

With the government now publishing data on students by funding cluster we can get a clearer idea of where Commonwealth Grant Scheme money goes.

My calculations are for 2018, and based on multiplying equivalent full-time student numbers in Commonwealth supported places by the relevant funding cluster rate. Due to the demand driven funding freeze and some universities over-enrolling allocated places the overall total exceeds what universities were actually paid. However, as it is usually not possible to specifically identify ‘over-enrolled’ students I am going to assume that this does not affect relativities between the clusters.

As the chart below shows the science, engineering and surveying funding cluster is by far the biggest recipient of Commonwealth funds, at $1.8 billion in 2018 (and this is missing the maths and statistics buried in another cluster). The health-related clusters between them received $1.6 billion, and this is also an under-count due to some health courses being in other clusters.

As is the case with public research spending, public tuition subsidies are skewed to STEM and health clusters. They have 32 per cent of EFTSL but 48 per cent of funding. The humanities, which are the subject of much of the controversy around higher education, received the least money of any cluster, $151 million in 2018. This is 2.1 per cent of the total.

However, it should be noted that other subjects typically taught in Arts faculties are in other funding clusters. For example, fields such as politics and sociology are in the second largest funding cluster by dollars (which also includes psychology, social work, and similar fields) and in the fourth largest funding cluster by dollars, which includes foreign languages and media and communications, which despite a recent downward trend has grown significantly over the last decade.

(Last paragraph added after original publication after Twitter commentary.)