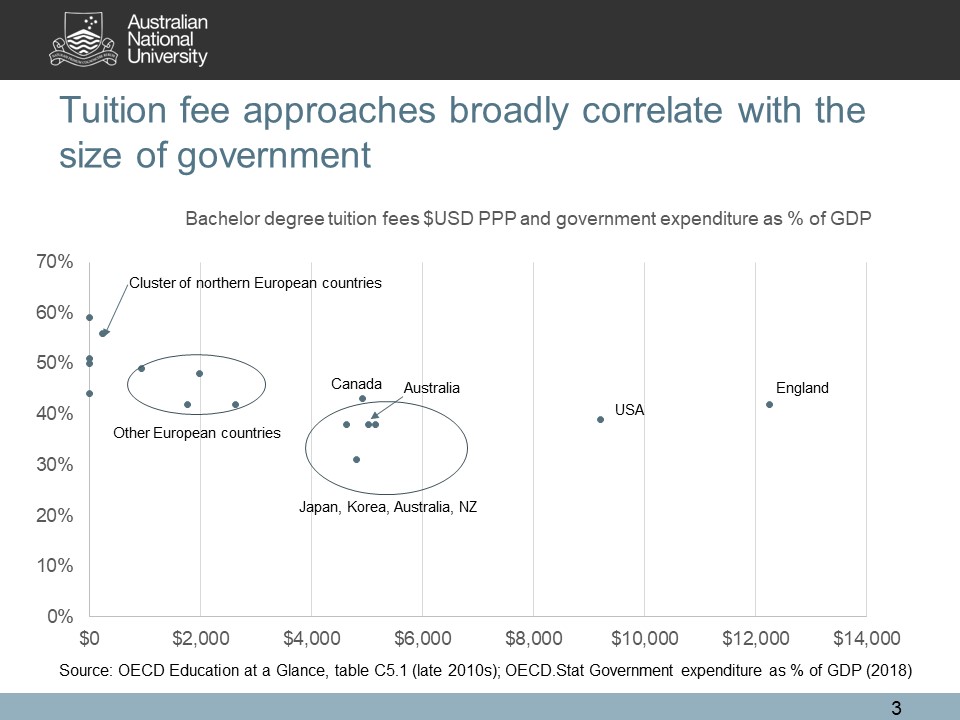

In a previous post I argued that Australia’s practice of charging fees for higher education reflects its broader patterns of taxation and public funding of social services.

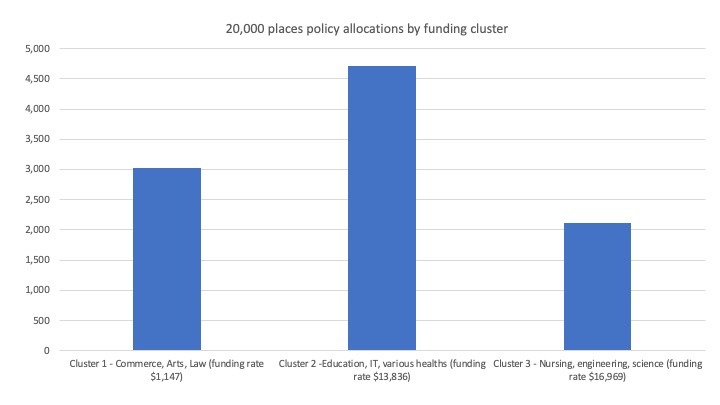

But we have had free higher education before, 1974-1988. For a government already spending over $600 billion a year the cost of free higher education is not beyond the feasible range. I estimate costs at $4.6 to $5.9 billion a year on status quo numbers of student places in public universities. The range reflects uncertainties about how domestic students currently paying full fees would be handled. The $4.6 billion transitions currently Commonwealth supported students to free, while the $5.9 billion fully compensates universities for lost fee revenue.

Of the arguments for free higher education the one that people find most intuitive is that it would increase higher education participation. People consume more when prices go down. But somebody is paying – the government on behalf of taxpayers – and so how they would respond is the key variable in whether the number of students would go up or down.

Debt aversion

Supporters of free higher education often make demand-side arguments, that fees or loans are a deterrent to higher education participation, especially to people from disadvantaged backgrounds.

As someone with working class origins free higher education advocate Duncan Maskell says he would not have gone to university if he had to take out a loan. Occasional school student surveys have picked up similar sentiments. But the ‘debt aversion’ hypothesis has always had trouble distinguishing between sensible prudence around taking out debt that probably is not worth it (good debt aversion), and over-caution in taking out debts that would probably lead to significant long-term benefits (bad debt aversion).

Read More »