The 2024 Graduate Outcomes Survey finally came out this week. As recently as 2021 the GOS came out in the year it covered, not September the following year. The government’s inability/refusal to release data in a timely way means that we need alternative sources of information for sector-relevant trends. This post reports on the GOS and brings in job advertisement and ABS data.

2024 graduate employment results

What I found in alternative sources for 2024 graduate outcomes made me concerned. The ABS labour force survey showed a downward trend in employment for young graduates. If this was right, was it cyclical or something more structural, such as AI reducing entry-level employment? A couple of recent US studies, one specifically looking at recent graduates, suggested an AI impact.

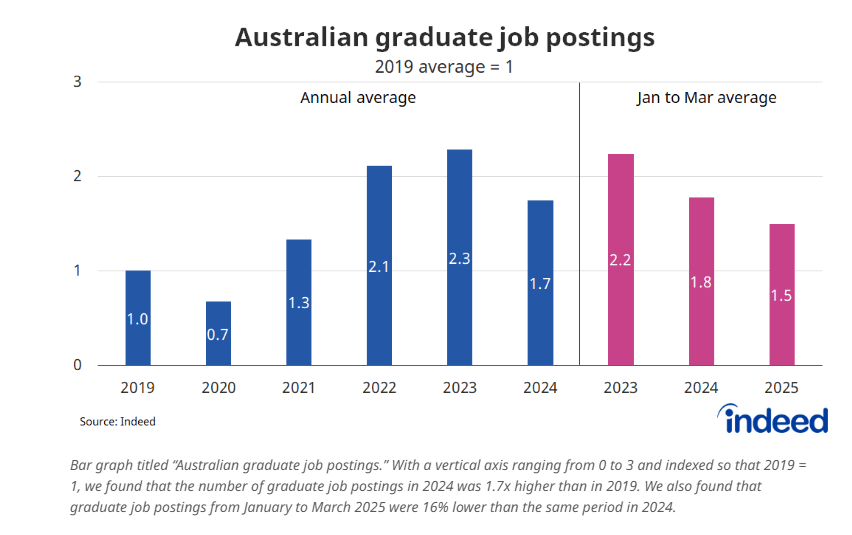

In May 2025, Callam Pickering looked at online job ads for graduates. He found that ads mentioning graduates declined in 2024 compared to 2023 – although they still exceeded 2019 levels. At least to March, ads for graduates in 2025 were tracking below the same months in 2024.

Fewer job ads targeting graduates cannot be good news, but I am not sure how important these are to the overall graduate labour market. There would be jobs typically taken by recent graduates that are not part of graduate programs or exclusively marketed to graduates. As work-integrated learning becomes more common, are firms increasingly hiring people they already know, recruiting graduates but not using advertising to find them? In analysis based on the 2023 GOS, but only graduates from institutions that had paid extra for WIL questions, 19% of people with new undergraduate qualifications said they had secured employment with a WIL employer and another 10% through a network contact made during their WIL experience.

Read More »