Last year the Parliament passed legislation making Commonwealth supported places demand driven for Indigenous students enrolled in medical courses. It sounded good, we need more Indigenous doctors. But as I pointed out, the policy as legislated risked reducing non-Indigenous medical student enrolments without increasing Indigenous medical students enrolments.

The 2026 funding agreements reveal that the Department of Education has been quite inventive in finding a workaround to prevent this perverse outcome. The price, however, is yet more complexity in higher education policy.

The problem

A demand driven funding policy for Indigenous medical students assumes that fixed total funding holds Indigenous enrolments down. Student places are indeed unusually restricted in medicine. Medicine is the only ‘designated’ course, meaning that the government sets a specific number of student places. While designation does not prohibit over-enrolments (i.e. student contribution only places), medicine also has a completions cap. A standard funding agreement clause specifies that a university must not change its medical enrolments in ways that will change annual completions from the capped level.

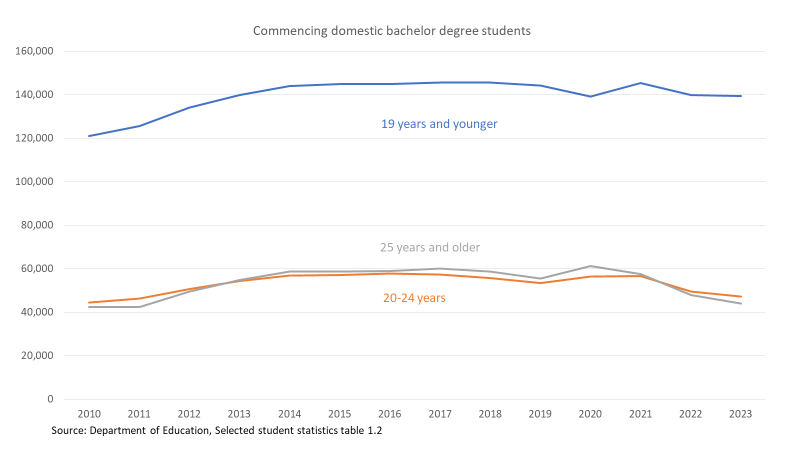

While medical student numbers are restricted it is not clear that this prevents increased Indigenous enrolments. As I argued in my original post, universities already try hard to recruit Indigenous medical students, with special entry schemes and quotas in some cases. On the available data (below) these schemes are delivering Indigenous enrolments, a source of pride for the medical deans association. 3% of domestic medical students are Indigenous, compared to 2.3% of the overall domestic student population.

The main obstacle to further enrolment increases is unlikely to be funding. It is finding potential students who are not being set up to fail.