For a side-project I’ve recently engaged with the subject of whether higher education funding systems shape the educational and career choices of students and graduates.

On one theory, where fees are charged students focus more on courses and jobs with high pay. Courses that satisfy intrinsic interests but do not offer good salary prospects would be less popular in countries with fees or after fee increases. Focus-group research on the views of students in European countries provides some support for this view (I have not cross-checked this against enrolments).

Under fee systems, depending on loan arrangements, taking courses with good job prospects may be necessary to reduce the risk of default on student debt repayments.

On another theory, also with some evidence from the European focus-group research, students in fee-paying countries may be more interested in courses that lead to personal financial rewards than courses that serve some broader public purpose. There are echoes of this argument in the local complaint that Australian higher education in the ‘neoliberal’ fee-charging era has lost sight of the ‘public good’.

I’ve discussed the role of interests in course choices before. In this post I look at the attitudes of graduates. My data source is survey evidence from the International Social Survey Programme. Unfortunately Australia only occasionally participates in these multi-nation comparative studies, but the ISSP’s 2015 work orientation questionnaire has Australian data.

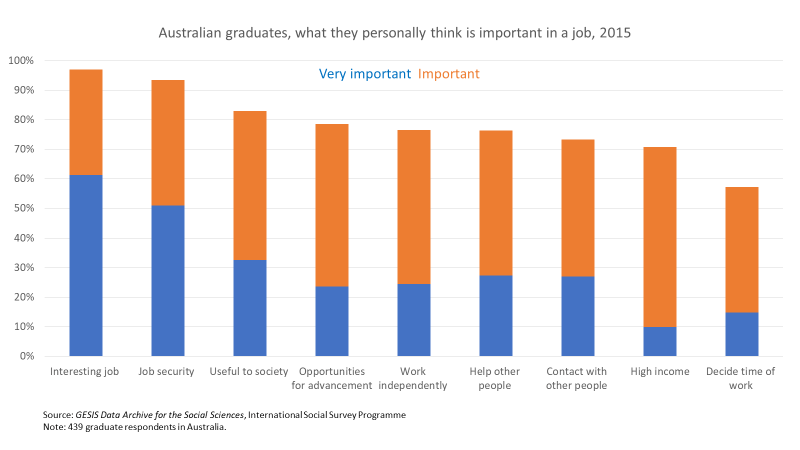

What Australian graduates see as important in a job

In the ISSP respondents are asked what job attributes they personally see as important.

A job being interesting is the single-most desirable attribute of a job for Australian graduates. This is consistent with interests being the dominant factor in course choice.

The ISSP question has two other-regarding options, being useful to society and helping other people. I presume helping others is a hands-on form of being useful, such as a teacher or nurse, while a policymaker, engineer or executive can produce useful-to-society structures and systems without directly helping specific individuals.

Perhaps because being useful to society is more general it is rated above helping others, and is the third mostly highly rated attribute overall.

Only 10% of graduates rate a high income as very important, the lowest of any attribute and the overall importance of money is the second-lowest of the options given. Money is nice to have but other job attributes are more important.