The government’s HELP legislation, cutting student debts by 20% and introducing a new repayment system, was introduced into Parliament yesterday. While I have criticisms of the 20% cut, it will be implemented and once done cannot be reversed. The changes to the repayment system will pass now but can, and probably should, be changed at a later date.

In this post I briefly explain how the repayment system will change and then discuss the choice of the first threshold.

The current and proposed student debt repayment systems

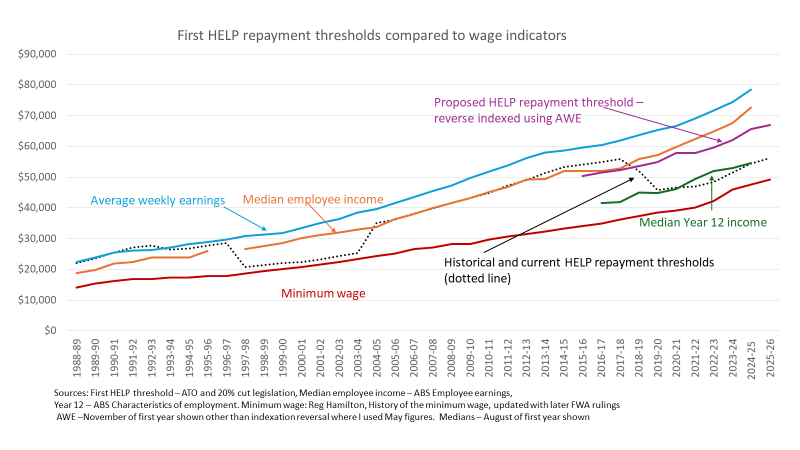

Under the current system, repayments start at an annual income of $56,156, at which point student debtors repay 1% of their total income. From there the percentage of income repaid increases incrementally to reach 10% of income at $164,712.

Under the new system repayments start at when income exceeds $67,000. At this point a marginal rate of 15% of income above $67,000 applies up to $124,999, where a marginal rate of 17% applies for income of $125,000 or more. Unexpectedly the bill restores part of the old system with an annual repayment cap of 10% of total income. This avoids some high income earners paying more than now.

The new thresholds will be indexed to growth in average weekly earnings. The current thresholds are indexed to CPI.

The logic of the first threshold

As the chart below shows, in the black dotted line, the first repayment threshold has changed over time. The long-term policy/political tension is between the idea that graduates should enjoy some financial advantage before repaying their student debt and the idea that student debt should be repaid except in cases of financial hardship. The policy pendulum is currently shifting from the latter to the former.