Update 20/12/2025: More recent data here.

—————————————————————————————————

I won’t have the capacity to produce another edition of my Mapping Australian higher education report in the foreseeable future, but I am extending the life of the October 2023 edition by updating the data behind the charts.

Mapping‘s chart data is the only publicly-available source of long-term time series data on many higher education topics, especially on financial matters.

I had been waiting on the 2023 university finances report before releasing another chart data update. That finally happened yesterday. Despite a record 27 universities reporting deficits, in the aggregate there was a small surplus, after a loss overall in 2022.

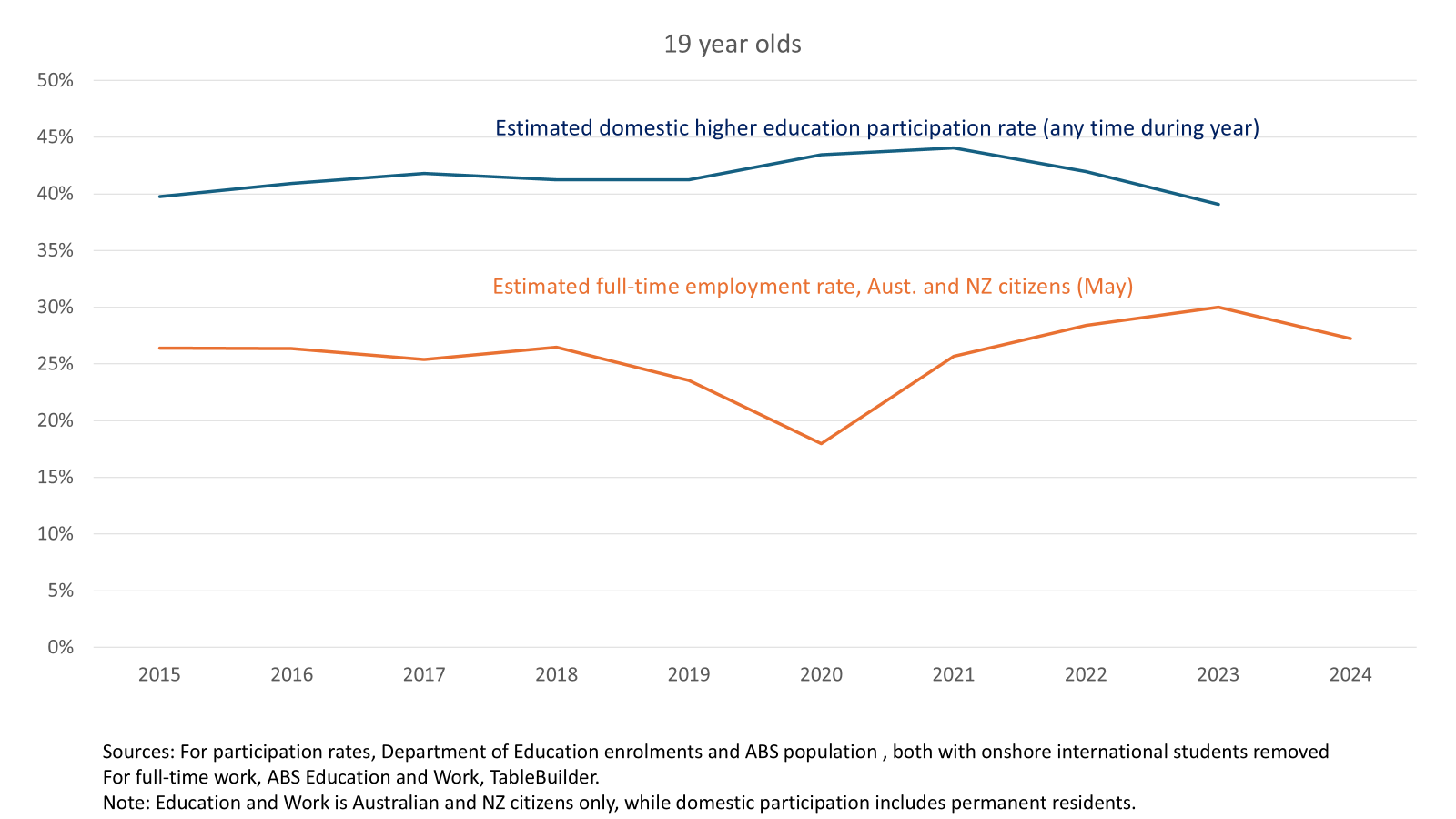

2023 had some weak numbers for the two main Commonwealth student programs, the Commonwealth Grant Scheme and HELP. Several factors were behind this: temporary COVID places coming out of the system, Job-ready Graduates reductions in total funding rates for some courses, and weak domestic demand. These programs trended up in 2024 and 2025, as seen in the chart below, although high CPI-driven indexation was a significant factor.

The updated chart data is available here.