In a previous post I argued that Australia’s practice of charging fees for higher education reflects its broader patterns of taxation and public funding of social services.

But we have had free higher education before, 1974-1988. For a government already spending over $600 billion a year the cost of free higher education is not beyond the feasible range. I estimate costs at $4.6 to $5.9 billion a year on status quo numbers of student places in public universities. The range reflects uncertainties about how domestic students currently paying full fees would be handled. The $4.6 billion transitions currently Commonwealth supported students to free, while the $5.9 billion fully compensates universities for lost fee revenue.

Of the arguments for free higher education the one that people find most intuitive is that it would increase higher education participation. People consume more when prices go down. But somebody is paying – the government on behalf of taxpayers – and so how they would respond is the key variable in whether the number of students would go up or down.

Debt aversion

Supporters of free higher education often make demand-side arguments, that fees or loans are a deterrent to higher education participation, especially to people from disadvantaged backgrounds.

As someone with working class origins free higher education advocate Duncan Maskell says he would not have gone to university if he had to take out a loan. Occasional school student surveys have picked up similar sentiments. But the ‘debt aversion’ hypothesis has always had trouble distinguishing between sensible prudence around taking out debt that probably is not worth it (good debt aversion), and over-caution in taking out debts that would probably lead to significant long-term benefits (bad debt aversion).

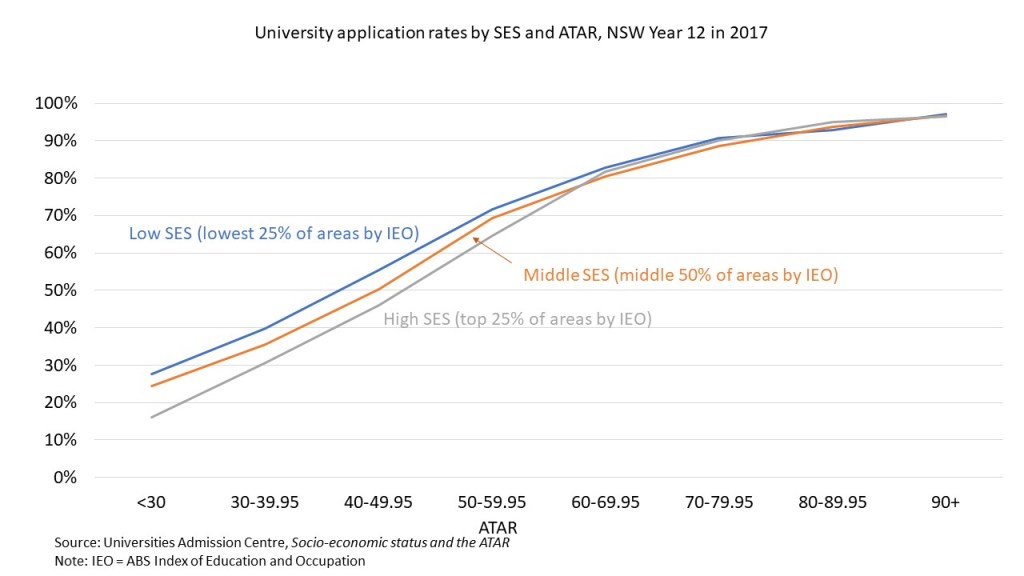

Conditional on finishing Year 12, the overall patterns of applications we see in the chart below look sensible. Application rates go down with ATAR, presumably mostly reflecting student preferences for less academic study and work, but also recognising the associated risks of not finishing a degree, which are closely linked to ATAR. In the main university-going 70+ ATAR ranges application rates are almost identical across the SES spectrum. If there is any ‘bad debt aversion’ among Year 12 students it appears uniformly across all SES groups.

In the lower ATAR ranges low SES Year 12 students are more rather than less likely to apply than higher SES students. Are they less debt averse? Low financial literacy and a poor ability to assess risks can work in both directions; a flat refusal to take on debt they fear and an over-willingness to take on debt to consume now without fully understanding its consequences.

There are other hypotheses I would explore here. Perhaps in lower SES groups the students who get an ATAR are already committed to the idea of university, while other SES groups face more pressure to continue with Year 12 regardless of post-school plans. Or perhaps low SES students on average have weaker job search networks, parents less able to line something up for them, and so university is a more necessary route to a career.

Whether or not social scientists can identify some bad debt aversion in survey research it’s a weak argument for free education. It requires spending billions on people who are not debt averse (as they already using HELP), and on average come from relatively affluent backgrounds, because there are some individuals, especially those from low SES backgrounds, who are due to their bad debt aversion making poor life choices.

Wouldn’t it be cheaper just to subsidise the low SES groups, or cheaper still try to persuade them to make choices that would lead to significant lifetime financial benefits?

Supply rather than demand

Every school student survey I can find since 1989 finds majority interest in higher education. Where the results are reported by social background low SES students are less likely than high SES students to say they aspire to higher education. But interest levels are still high. In this survey of Year 8s more than 60 per cent of low SES students aspired to university.

Academic results and improved understanding of what qualifications are required for preferred careers will moderate this demand, but like most policy analysts in this field I have taken the biggest problem to be the supply of student places rather than demand for them. There is no point trying to increase already high demand for higher education by making it free if there are too few student places to meet that demand.

The major objection to free higher education is that it would make increasing supply more difficult.

Student contributions and budget constraints

The strength of the current system is that with student payments the government can spread its available funds over a larger number of people. That was the reason for introducing HECS in the first place.

For later governments HECS gave them more policy options. If they needed to make budget savings they could increase student contributions rather than cut student places (bad for the prospective students who miss out) or funding per student (bad for the students who get in).

Free university would put higher education into intense, high stakes, zero-sum budget competitions against all other beneficiaries of government spending, and with those who want to moderate the tax take.

While higher education has done better out of government than the sector narrative says, history suggests that higher education mainly does well when the budget is in good shape. When budgets are tight higher education is always over the last half century a target for savings, as the chart below suggests. Based on history, current budget forecasts don’t look good for higher education.

In his argument for free higher education Duncan Maskell makes the point that graduates pay more in tax than other people, but that’s only many years in the future. It does not help much in annual budget setting.

Participation rates

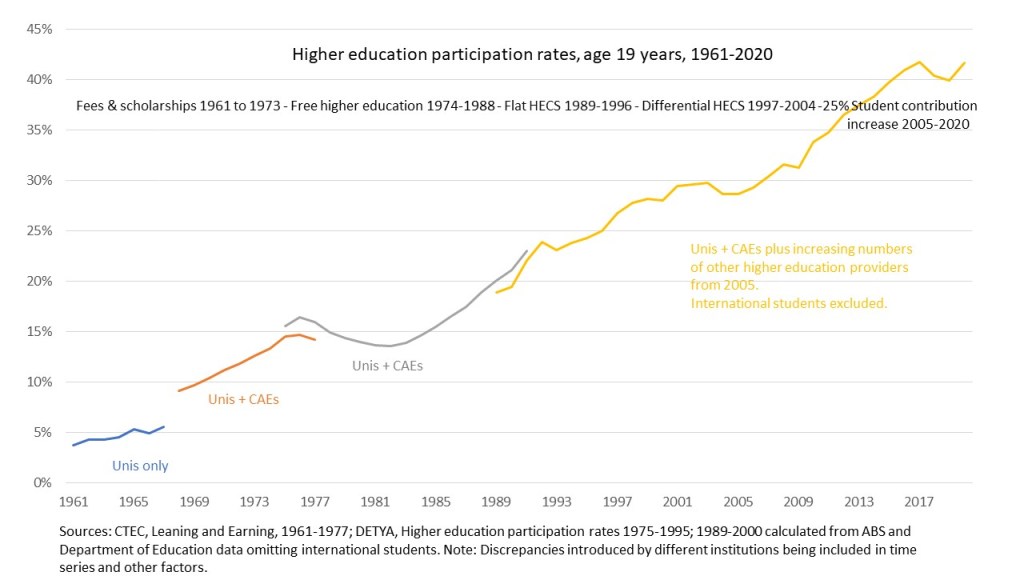

My previous free higher education post argued that higher education attainment rates have increased around the world regardless of funding system. In Australia participation rates in higher education at age 19 years have increased through several changes of funding regime over the last 60 years (chart below). The most sustained although still temporary decrease in participation, however, was in the free higher education era.

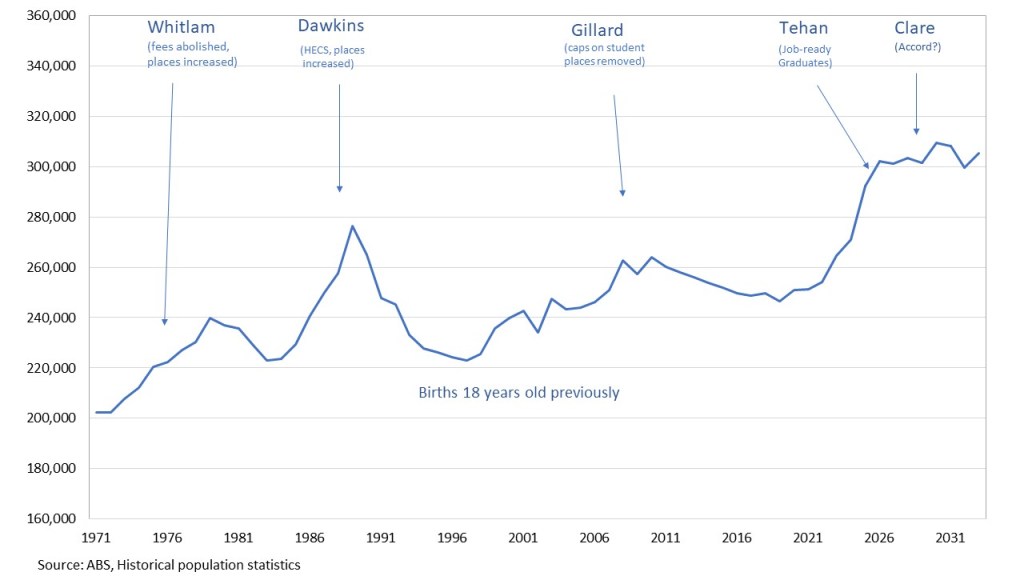

Exactly what happened in the mid-1970s to early 1980s has not been explained in an entirely satisfactory way. A decrease in male school retention rates was probably a factor, but with funding essentially flat there was little financial capacity to increase places in response to demographic growth up to 1980 (chart below).

Population increases and fiscal constraint (two charts back) are a bad combination. We face this scenario again from the mid-2020s. Dan Tehan tried to deal with it by increasing student contributions. With a free higher education system that option would be unavailable.

While lower participation rates are not inevitable under any system, free higher education in current demographic and budget circumstances would create a high risk that participation rates would fall.

What happens to low SES university prospects when supply falls further below demand?

Low SES students on average have lower ATARs. As universities usually use academic criteria to ration scarce places this puts low SES applicants at more risk from reduced supply. This happened when universities reduced commencing places in the early 2000s due to the then minister’s objection to ‘over-enrolments’ (enrolments in excess of public funding allocations), and it might have happened again with the end of the demand driven system in 2017, although as with the 1970s dip I doubt student place supply issues fully explain why low SES enrolments trended down 2018-2020.

Conclusion

In Parliament yesterday education minister Jason Clare was asked whether he planned to make higher education free. He clearly – and from my perspective correctly with current demographic trends – sees the main issue as ensuring the supply of student places, which counts strongly against a policy of free higher education.

Another great post. HECS is already the best deal any of us will ever get.

Targeted financial support for poorer students would seem to be a much more effective way of overcoming disadvantage – would be interested to know if you think there is data to support this.

LikeLike

The main means tested scheme is student income support. While it is very plausible that it increases participation the most empirically robust research only looked at completion rates, and found it had a positive effect: https://andrewnorton.net.au/2020/12/17/youth-allowance-and-course-completion/

LikeLike

Have other measures to increase low SES university participation been investigated? As someone with a low SES background myself, one of the habits I can’t break is extreme risk aversion. My preference is always a shorter program, getting a qualification now, rather than a better one later. One way to address this is with nested programs, where the student can get qualifications on the way to a degree. Universities don’t like this option, so it might take some government financial incentive, or regulation.

LikeLike

Sort of. Enabling courses are on example although not a qualification. There are also diploma pathways that articulate into the second year of a target bachelor degree, although a lot of these are full-fee courses run by private colleges.

LikeLike

Absolutely spot on Andrew

LikeLike