I am not opposed to changing international student migration rules and education provider requirements to moderate problems long associated with international education, including “dodgy” colleges, inadequate student preparation, student poverty, student exploitation and “permanently temporary” migration.

Multiple steps towards minimising these problems have already been announced or taken, with increased financial requirements for a student visa added last week. Most changes announced before last Saturday are justifiable.

But capping international student numbers including down to a course level, as announced over the weekend, is a bad move.

The caps will face all the problems I have identified with bureaucratic allocation of domestic student funding. Because numbers will be allocated between universities and courses according to a politician or bureaucrat’s view of where students should enrol, rather than where students want to enrol, actual enrolments are likely to be well below the capped level.

Capping at a course level to meet skills needs

The international student policy paper released on Saturday has a strong emphasis on the idea that international education enrolments should more closely reflect Australia’s skills needs (pp. 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18, 22, 27, 37).

The paper tells us that:

“While international students are an important source of potential skilled migration, student enrolments have not always been aligned with our national skills interests. In 2023, for example, 35 per cent of tertiary level international students studied business and management—skills not generally in shortage in Australia—and only 8.7 per cent studied in areas of health and education.”

Yet it is far from obvious that course level enrolments should be a consideration for international student policy.

International students should follow their own interests and career plans

The current practice and policy is that most international students go home. A minority of former international students become permanent residents, while the others leave after completing their courses or after time on other temporary visas (following policy changes announced late last year, a shorter time in future).

People who will spend their most of their working lives in non-Australian labour markets should be free to take courses that reflect their own interests and career plans.

As was argued in the Job-ready Graduates debate, governments have limited influence on course choices. While prospective students often have multiple interests to choose between, few people sign up for courses and careers that do not interest them. At least for domestic students, few people who applied for business courses have second or lower preferences for health or education courses.

Some international student interests and career plans overlap with skills shortages in Australia. As occupations with skills shortages are typically favoured in migration policy, the prospective students with a strong interest in migration already have an incentive to take these courses from amongst the courses that interest them.

Should we encourage international students to take fields with placement bottlenecks?

Although domestic student enrolments have responded to skills shortages in health these shortages remain. This is not usually due to weak domestic demand. Although the Department of Education has failed to release applications data since 2021, offer rates for domestic health applicants are typically relatively low. Across all health courses in 2021, the offer rate was 68.9% in 2021 compared to 82.8% for all courses.

One reason for this is the clinical placement bottleneck. Health courses require placements in real-world medical workplaces, and a shortage of these is an obstacle to expanding enrolments.

Allocating scarce clinical training places to international students increases the risk that course graduates will move overseas and not be available to the Australian labour market. Accepting international students in business courses makes sense because they will not detract from Australian labour supply.

Can regional universities benefit from capping institution-level international enrolments?

The international student policy paper wants to steer international students away from the big cities to regional universities. This is partly to “alleviate current pressures on accommodation, transport and other infrastructure” and partly to “advance the viability of regional providers”. This would mean lower caps relative to current and expected enrolments for city universities and higher caps for regional universities.

But taking the government’s policy agenda as a whole it is hard to see how the “viability” of regional universities will be enhanced.

Just last month a government paper on the points-tested migration system suggested getting rid of one of the key incentives for international students to attend a regional university, which is additional points towards a points-tested visa. (Although absurdly most areas apart from Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane are classified as “regional” for migration purposes.)

The other appeal of regional universities for migration-focused students is relatively low fees. That will remain, but lifting the amount of money students need saved to get a visa from $21,041 in October 2023 to $29,710 now will create new obstacles for these financially constrained prospective students (not that this increase is wrong; I am just noting the regional university implications).

Along with a shorter subclass 485 temporary graduate visa after course completion to recoup study costs, regional universities will suffer from all the policy changes except the caps.

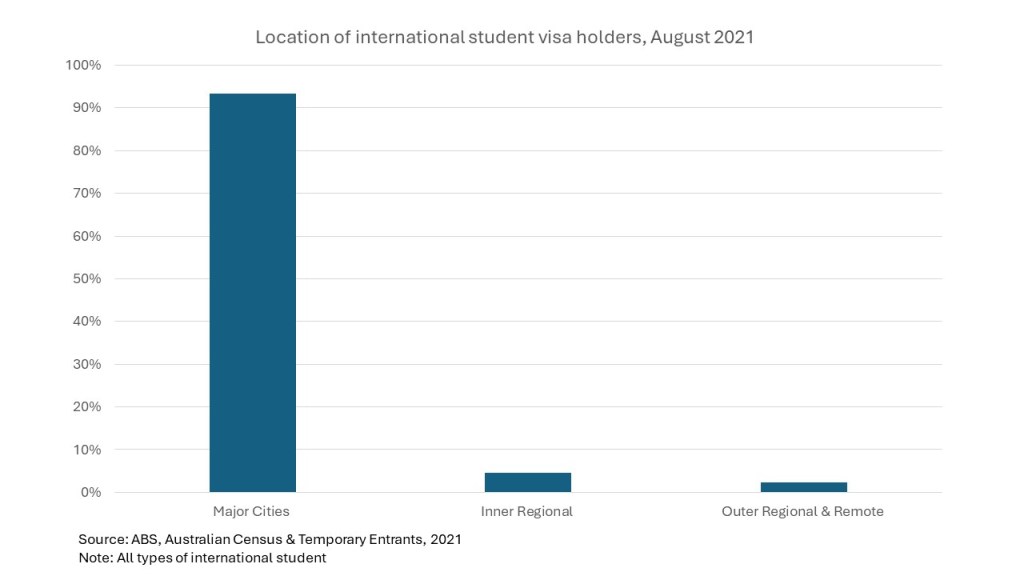

Despite current incentives for regional study most international students don’t want to live in an Australian regional city or town, for completely understandable cultural and social reasons, along with prestige factors for some students. Less than one in ten international students lived outside the major cities in 2021.

The stranded places problem

Capping international student numbers by university and course will lead to the stranded places problem – student places that are theoretically available but cannot in practice be used. Every condition added to the use of a student place reduces the chance that a student can be found who meets the all the criteria.

In this case, the goals of the policy are to get international students to enrol in courses we already know they mostly do not want to take, and to attend universities we already know that none but a small minority want to attend, despite migration and financial incentives to do so.

As a result, the actual number of international students enrolled under the capped system is likely to be significantly less than the total number of available places. International students won’t enrol in courses and universities that don’t meet their needs.

Under a less politicised system this could be partly managed by setting a formal cap that is higher than the actual target number, knowing that some courses and universities will not reach their target. The target range model proposed for domestic students is designed to manage this, recognising that in a given year some universities are likely to exceed and others fall short of their targets.

But in the domestic and international cases the political incentives are reversed. For domestic students the government has an interest in saying that student places will be plentiful. But for international students the political value of capping will come from announcing a specific capped number that will clearly reduce student numbers compared to current levels and growth trajectories.

Conclusion

While I understand the political need to control international student numbers and can support most of the visa changes, the capping decision should be opposed.

In addition to the problems identified above, capping international enrolments takes another step away from a rules-driven higher education system, in which students and education providers can make decisions based on known legal criteria, to a system based on ministerial and bureaucratic discretion.

As we have seen from the domestic student funding agreements, governments use this discretion to increase their broader control over the higher education sector. This includes implementing policies that should have gone before the Parliament. The introduction of caps will require legislation, but the specific caps will be decided administratively.

High levels of political discretion distort university decision-making even when universities officially have a choice. Because universities feel they need political favour they sign up to bad deals like the nuclear submarine program that are guaranteed to lose them money.

A decade ago public policy was more rules-based than it had ever been before, with the creation of TEQSA and the introduction of demand driven funding for bachelor degree students. International education has always been subject to changing migration policy, but there was no thought then that politicians and bureaucrats should interfere in the specific decisions of students and universities.

Since the late 2010s we have moved a long way away from rule-based policies. We are now in new political territory. For the dependence reasons above I will be pleasantly surprised if the sector pushes back strongly against Commonwealth government over-regulation and micro-management. But it should resist these changes for the worse.

Update 20/05/2024: This post has the legal detail on the caps.

Update 27/05/2024: This post proposes a cap-and-trade system to make the caps more flexible and efficient.

Spot on, as always! It seems the notion of caps, driven brazenly but a reactive political response to the popular notion that immigration is a key factor in a housing crisis, is likely to result in a blunt force intervention focused on raw student visa numbers rather than the varied durations of stay, purpose and source within that broad category. This, in turn, could create awful incentives for institutions. Exchange students present for one or two semesters, and much more likely to be in a homestay or dedicated student accommodation, might be sacrificed for the high yielding full-fee degree berths if HEIs find themselves up against a cap. Australia’s outbound student programs depend on reciprocal partnerships. The risk of such distorting incentives under a cap regime in turn would give rise to arguments for even more micro-management, of student status type in addition to the problems Andrew draws attention to in any attempt to specific course-level caps. Would there be rules then to reallocate spare ‘stranded places’ to non-degree exchange students in the next academic year, or some such? The hundreds of MoUs Australian universities have with foreign partners that govern student mobility would be under a shadow.

LikeLike

A minority of former students become permanent residents? Really? What percent? 49.98 is still a minority. A lot of people think many former students become permanent residents. That’s why they come here. To migrate, not to take their skills back home and help develop their country

LikeLike

Less that 20% for 2010s arrivals, see this Grattan Institute report: https://grattan.edu.au/report/graduates-in-limbo/

LikeLike