Today the government announced big changes to the HELP repayment system. Its proposal involves several interconnected conceptual and practical considerations.

The first issue is where to set the first repayment threshold – how much should a HELP debtor earn before they start repaying? The government proposal is for a higher first threshold.

The second issue is annual repayment amounts, which affect the disposable income of debtors and how long it takes them to repay their debt. The government proposal is for most debtors to repay less HELP debt each year, increasing their annual disposable income but also their repayment time.

The third issue is the method of repayment. Should it be – as we have had since 1989 – a system which levies a % of all income when income reaches a threshold, or should we have a marginal rate system, which is a levy on income above the threshold (like the current income tax system). The government has decided on a marginal rate system.

All three issues intersect with the public finance element of HELP – the cash flow implications of the changes for the Commonwealth, and the costs in interest subsidies and bad debt. These will all be negative for the government.

In this post, I will look at the annual repayment implications for debtors, effective marginal rates of repayment, and make some initial comments about selling this reform to debtors and voters.

What the government proposes

The first threshold for repayment will go to $67,000, from $54,435 for 2024-25, and approximately $56,000 after CPI indexation for 2025-26 (I have assumed 3% indexation, which seems to be around what the government has estimated).

From this first threshold of $67,000 we will move to a marginal rate of repayment, at two levels – 15% from $67,000 to $124,999 and 17% from $125,000. These rates would replace the current whole-of-income rates ranging from 1% to 10%.

The chart below illustrates the difference for a HELP debtor earning $70,000 a year.

Overall annual repayment levels

The media has been given a figure of an average reduction in annual repayments of $680. In 2021-22 the average repayment was just under $4,000.

Lower annual repayments are not, however, an inherent feature of marginal rate systems. Whether or not repayments are lower or higher depends on the threshold levels and repayment rates. The table below is from a government explainer. The chart below the table offers more detail and shows the jagged line caused by the large number of incremental increases in repayment rates.

In the government’s policy, repayment reductions are driven by the high first threshold of $67,000. A quirk of the marginal rate repayment system, compared to our current whole-of-income system, is that a high first threshold delivers more savings to high than low income earners.

Under the current system, a person earning $67,000 would repay $1,340 (1.5% of $67,000). But a person earning $167,000 would repay $6,700 on their first $67,000, because they repay 10% of their entire income. Under the proposed system, a person earning $167,000 would repay nothing on their first $67,000.

Diminished effective marginal tax rate benefits

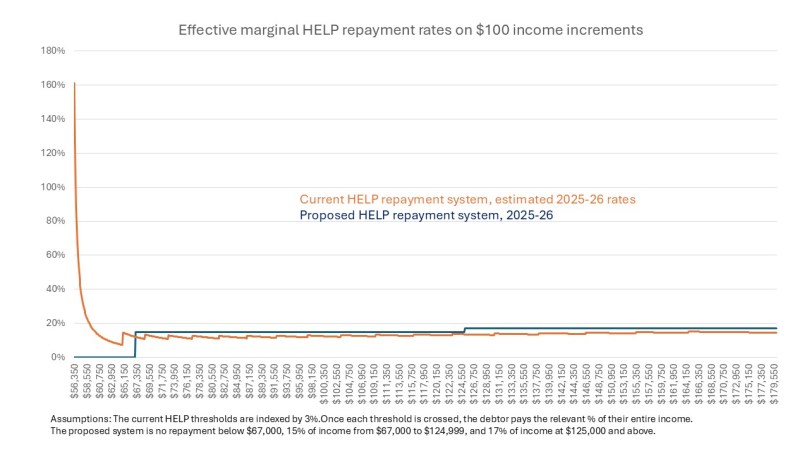

A usual benefit of marginal repayment systems is reducing the high ‘effective marginal tax rate’ (EMTR) of moving into repayment or up a repayment threshold (we currently have 18). At each threshold point, the debtor pays a higher percentage on all their income, not just the amount above the threshold.

A high HELP EMTR can act as a disincentive to work additional hours, as the government’s explanatory material notes. In extreme cases, just above the first threshold in the current system, an increase in income can result in less take-home pay. In the chart below I have left out some of the initial $100 increments because the EMTR is so high that the y-axis scale makes it impossible to read what is going on at higher incomes.

In this reform, however, the EMTR benefits only apply for incomes up to about $60,000. Because exempting income below $67,000 benefits all repaying debtors, and not just those earning between $56,000 and $67,000, it reduces repayments significantly. To recover revenue that would otherwise be lost the government decided to impose high marginal rates. This means that most repaying debtors will have a higher rather than lower EMTR than under the current system.

The politics of the rates

The initial media release on these changes did not mention the actual rates, and nor did the accompanying media stories.

This I think will be the biggest political problem. I’m not looking forward to having to explain – possibly in a one or two minute radio spot – why a 15% repayment rate will cost a HELP debtor less than a 2.5% rate (to use the $70,000 income example).

The education minister is a more talented simplifier than I am, but even he decided to dodge this issue for day one media.

In subsequent commentary I will look at other issues with the HELP repayment reforms.

Andrew,Love your work and dedicati

LikeLike

Thanx for this most informative explanation.

The government proposes to change HELP repayments from a small percentage of a big part of debtors’ incomes to a bigger percentage of a small part of debtors’ incomes.

How much debtors have to repay each year depends on the percentage repayments and the parts of debtors’ income the rates are applied to.

The Government has chosen rates and the part of income they are applied to which would lower substantially the amounts debtors repay each year and increase the number of years over which they repay the smaller amounts.

LikeLike

I am seeking to clarify if this proposal is a new repayment schedule ie changes to the terms of a loan replayment which is pay off the loan over a longer period; or if the proposal is that the Government is proposing that this more targeted debt forgiveness or write off for students with taxpayers generally liable; or is it both. The proposals and critique I am reading confuses.

LikeLike

So students at non-university providers will still have to pay the 20% ‘administration fee’ which cannot be abolished because the financial implications that the lost revenue cannot be covered, but a 20% discount can somehow be accommodated… my how times change for some…. so much for equity…. It is the students who are being charged this not the providers…..

LikeLike

There are two separate proposals – this post was written on Saturday before I knew about the 20% cut to total debt announced on Sunday,

As described by the government, all debtors benefit from the 20% while only debtors who would have earned $56,000-$180,000 in 2025-26 benefit from the repayment changes.

The two changes work in opposite directions for current debtors – 20% cut reduces repayment times while lower annual repayments increase repayment times.

LikeLike

Thanks

LikeLike