I’m not an historian, but decided to accept a Robert Menzies Institute suggestion that I give a paper on the 1957 Murray report on universities for their 2023 conference on Menzies, which covered the years from 1954 to 1961. The book chapter version of that paper came out in December 2024.

As well as describing events surrounding the Murray report I tried some counter-factual history, in an attempt to understand the distinctive contribution of Menzies to Australian higher education policy. The post-WW2 period saw higher education expand in all the countries with which Australia compared itself. With or without Menzies, Australia’s pre-WW2 model of one impoverished, low-enrolment university in each capital city was not a plausible long-term system.

But what would have happened if Labor had remained in power after 1949, or won the close 1954 election? What would have happened if someone other than Menzies had led the Liberal Party (or the main non-Labor party, given Menzies’ role in creating the Liberal Party)?

This post looks at what happened up to 1956. A subsequent post examines the Murray report and its consequences.

Universities and the Constitution

Successive High Court decisions over the last 100 years have largely neutralised the Australian Constitution‘s division of powers between the Commomwealth and the states. But the original Constitution gave the Commonwealth no power over education or universities, other than in the territories. Until the 1940s the Commonwealth had very little to do with universities.

In the 1940s three major developments changed that. Two of these were by-products of WW2, the other was a key legal foundation of the modern welfare state.

At the start of WW2 both the states and the Commonwealth levied income taxes. To help finance the war, in 1942 the Curtin Labor government legislated to effectively take income tax powers from the states. The states were compensated using section 96 of the Constitution, which lets the Commonwealth make grants to them ‘on such terms and conditions as the Parliament thinks fit’.

This started an imbalance between state and Commonwealth revenue raising that reshaped the federation. From that time, the states have lacked sufficient revenue to fund all their constitutional responsibilities, including universities. Recognition of this financial reality was part of 1940s debates about the Commonwealth increasing its role in higher education.

Using its defence power, in the early 1940s the Commonwealth introduced some regulations of and funding for universities. While limited to war-related matters, Labor’s minister for war organisation, John Dedman, told Parliament in 1943 he hoped that this was the ‘first instalment of a better order’.

By the mid-1940s Menzies – a former constitutional law barrister – was suggesting section 96 as a constitutional workaround to let the Commonwealth support the states to deliver higher education. Specific purpose grants to the states, as opposed to general grants, had been recognised as constitutionally valid by a 1920s High Court case (ironically Menzies was a barrister for the losing side). Despite this, specific purpose section 96 grants were still unusual. The federation was respected then more than now.

The section 96 workaround would not, however, straightforwardly support a peacetime extension of the Commonwealth Reconstruction Training Scheme (CRTS), which supported free technical and university education for people with military service. Section 96 does not authorise direct payments to individuals.

The 1946 Constitutional referendum

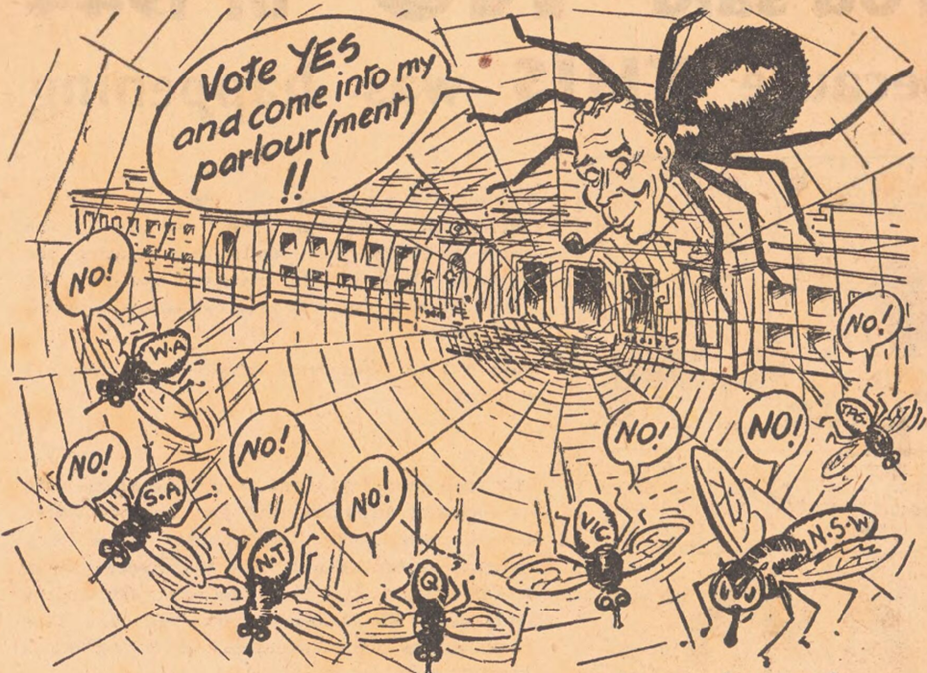

Labor’s solution to this problem was a proposed constitutional amendment, which would give it power to legislate for a variety of social services, including ‘benefits to students’. Along with two other referendum questions, this amendment was put to the people on election day 1946.

The Liberal Party, led by Menzies and contesting its first federal election, generally portrayed the referendums as a Labor power grab.

Labor PM Ben Chifley depicted as a smoke-piping spider.

Menzies, however, supported the social service amendent. Although speculative, this may be the first point where Menzies mattered – compared to another leader of the non-Labor forces – to higher education policy in the long run.

While Labor was returned to power in the simultaneous federal election, the social services amendment was the only one of the three referendum questions to succeed. But it was a narrow victory, 54% in favour overall and the yes vote below 52% in three states (to pass 4/6 states must be in favour).

It will always be speculative, but the position Menzies took on the social services amendment may have swayed some Liberal voters to support it, while voting against the other two changes. But voter self-interest in putting some existing benefits on a more secure constitutional foundation, or hoping to receive other welfare payments, may have been more important.

Menzies in office 1949-1956

Menzies won the December 1949 election, beginning a term in office that did not end until 1966. He continued with a review of university funding, the Mills review, which Labor leader Ben Chifley had announced before he lost office.

In 1951, Menzies legislated specific-purpose section 96 grants to the states for spending on universities and created the Commonwealth Scholarship Scheme using the benefits to students power. The section 96 grants funding formula linked Commonwealth grants with state grant and student fee revenue, ensuring that Commonwealth funding added to rather than replaced other funding sources.

What difference did Menzies make? – funding

Menzies had a great personal interest in universities. Possibly Commonwealth involvement in universities would have been slower under another non-Labor leader.

There was no in-principle difference between Menzies and Labor on the idea that the Commonwealth needed to involve itself in universities. Labor had initiated the 1946 social services referendum ‘benefits to students’ provision for that reason, and had commissioned the Mills review before it left office.

Policy detail may, however, have differed if Labor had remained in or returned to power.

Would Labor have created the link between Commonwealth grants and student fees? Abolishing fees entirely, as the Whitlam Labor government did in 1974, was probably too far ahead of federal Labor thinking in the 1950s. University fees were a matter for the states. But federal Labor politicians complained about university fee increases under the Menzies policy.

For the 1954 election Labor promised more university funding. Despite winning 50.7% of the two-party preferred vote Labor fell short on seats and the Menzies government remained in office.

What difference did Menzies make? – regulation

Another counter-factual is whether a Labor government would have attached more conditions to university grants. In his second reading speech on the 1951 section 96 grants Menzies said:

“It is not the desire of the Government to interfere in the internal management of the universities, nor to attach conditions to the use of these moneys which would interfere with the traditional liberty of the universities to determine the courses of instructions that they wish to pursue or the character of the research that they wish to undertake.”

On the Labor side, in the 1940s central planning was in fashion. Chifley may have gone down this path for universities. But I did not find critcism of this kind, taking Menzies to task for being too hands-off, in parliamentary debates. HV Evatt, Opposition leader from Chifley’s passing in 1951 to 1960, would be a strong contender for the title of the most academic person ever to lead a major Australian political party. It’s hard to see him endorsing university micromanagement.

Times still tough for universities

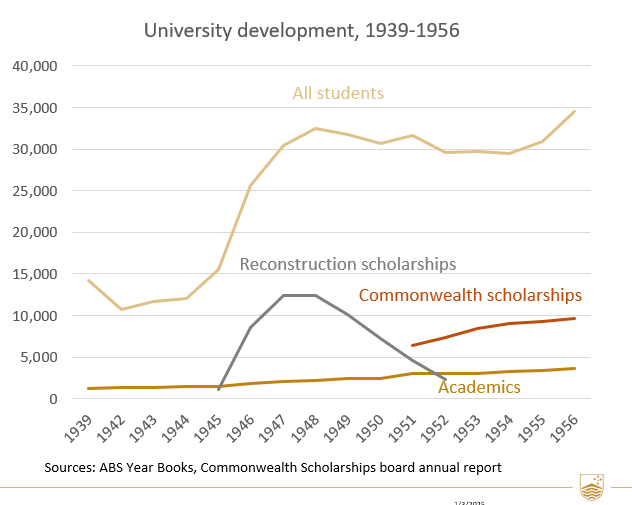

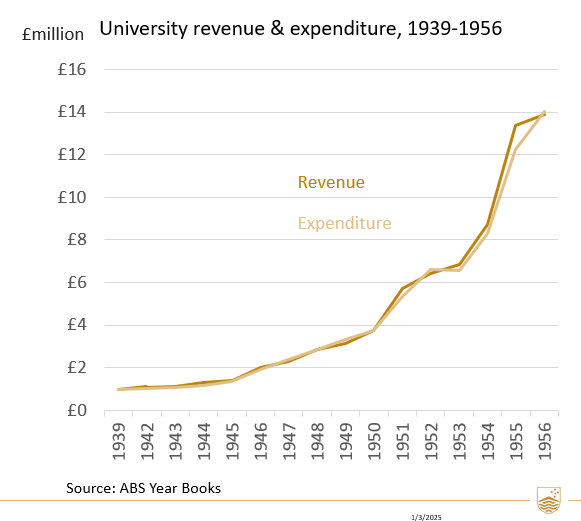

While constitutionally significant, the practical consequences of these early Menzies era changes were limited. High inflation in the early 1950s quickly eroded the real value of unindexed grants. Enrolments fell as the last of the CRTS students finished their education.

Universities continued to argue that they faced a crisis.

By 1956 student numbers were growing again but the sector’s always precarious finances had slipped back into deficit.

Menzies agrees to a review

At a dinner with vice-chancellors in 1956 Menzies agreed to a review of universities, what became the Murray review and report. The next post examines the Murray process in more detail.

Thanx for a most informative post.

LikeLike

hi Andrew did Menzies have a similar interest in vocational education or was it largely being progressed in the form of apprenticeships at the time?

LikeLike

No, he didn’t. From the mid-1960s a wider range of qualifications received federal funding – some of which I think would now be in the vocational space – but I don’t think there were any large scale funding programs for vocational education until the 1970s.

LikeLike