Update 28/11/2025: Last night the Senate passed the ESOS amendment bill with Coalition amendments. While I still believe this provision counts as very poor public policy – for reasons exanded up in my Senate inquiry submission – the Coalition changes do improve things somewhat. These are noted in the text below.

—————————————————————————————————-

The government is having another go at its 2024 Education Services for Overseas Students (ESOS) legislation, reintroducing it earlier this month minus the enrolment caps that saw it blocked in the Senate last November.

This post draws on and adds to things I wrote last year about proposed ministerial powers to suspend and cancel ‘classes of courses’.

The amendments discussed in this post were partly why I regarded the 2024 ESOS amendment bill as the single worst piece of higher education related legislation to come before the Parliament in my career.

What took it beyond standard bad policy was its use of broad ministerial discretion with minimal constraints on how it is exercised. That creates rule of law problems, making it hard to know in advance what the rules are. If passed, the amendments could lead to some education providers being arbitrarily punished for the actions of others.

Legislative references are to the section numbers of the ESOS Act 2000, as they are or as they would be if the bill passes unamended.

A mass course cancellation power

The bill gives the education minister power to simultaneously suspend or cancel multiple ESOS course registrations at multiple providers: division 1AB. It does this by making the unit of regulation a ‘class of courses’ – the definition of which is discussed below.

This mass cancellation power differs from existing laws that give the ‘ESOS agency’ (TEQSA in higher ed, ASQA in VET) power to suspend or cancel the registration of specific courses or specific providers: sections 83 to 92. It also differs from the current power of the immigration minister to issue a ‘suspension certificate’ to a provider. This can be done in specified circumstances such as fraud in visa applications, students breaching visa conditions, and other visa issues: sections 97 to 103.

Cancelling a class of course – definition

Sections 96B to 96E of the amending bill create ‘classes of courses’ as a legal category.

According to section 96B(4) a class of courses can be specified by reference to a) the kind of course; b) the kind of provider; c) the location of the course, or d) any other circumstances applying in relation to the course.

The breadth of 96B(4) is only limited by section 96B(1) which creates three broad rationales for cancellation. These are standard of delivery, skills needs, and the public interest.

Standard of delivery

Under section 96B(1)(a) there must be ‘systemic’ issues with the standard of delivery, which sets an imprecise but fairly high threshold for action.

Update 28/11/2025: This was amended to that it refers to ‘systemic problems’ rather than systemic issues. End update.

Section 96B(2), which sets out matters that the minister ‘may have regard to’, gives more specific examples that could be proxies for standard of delivery.

Updpate 28/11/2025: This was amended to ‘must have regard to’. End update.

One of these is completion rates – so all courses with completion rates below X% are cancelled?

Another matter the minister can have regard to is transfers from or to the course, with transfers out a possible indicator of low quality – but also possibly an indicator that the provider suffers from poaching of students, with students switching to courses that are lower cost but also lower quality. Transfers in might be seen as a positive sign, except that this may also indicate poaching.

A key difference between this bill and the equivalent provisions in last year’s bill is that the minister no longer must consult TEQSA or ASQA. Instead of specifically naming these regulators the minister must consult ‘such persons or entities’ as ‘the minister considers appropriate’ from a list in a legislative instrument that the minister makes: section 96B(6)-(8).

Update 28/11/2025: The minister must now consult with TEQSA and other quality regulators as approprite. End update.

The explanatory memorandum says that this ‘allows the required consultation to be flexible and respond to emerging risks’: p. 62. I can see that a range of organisations (employers, accrediting bodies etc.) could have relevant views on a specific class of courses. It would be excessive to list them all in advance. But that does not preclude requiring in the legislation, rather than just as a ministerial option, TEQSA and ASQA to be consulted if the minister wants to cancel courses on ‘standard of delivery’ grounds.

Failure to bring TEQSA and ASQA into the process could also mean that courses cancelled under ESOS for alleged ‘standard of delivery reasons’ would still be registered under other legislation for domestic students. That would be a confusing regulatory stance for students.

Skills needs

A class of courses can be cancelled if they ‘provide limited value to Australia’s current, emerging and future skills and training needs and priorities’: section 96B(1)(b).

Last year I was critical of Australia’s skills needs as a basis of enrolment capping or course cancellation. Australia’s skills needs are irrelevant to international education unless international students stay in the country for an extended period after course completion. Recent JSA analysis suggests the share of former international students achieving permanent residence is higher than other studies have found, but still 60% plus of international students will return home. Why should their course choices be restricted to the labour market needs of a foreign country?

If students want to stay they already have strong incentives to take courses favoured in the migration system, which is (at least in theory) attuned to skills needs.

For example, former international students with vocational qualifications cannot remain in Australia on a subclass 485 temporary graduate visa unless they have a qualification related to an occupation on the skilled occupation list.

Former international students with higher education qualifications don’t face this limitation, but if they want to stay longer than their 485 visa their occupation matters. For example, to get a subclass 482 Skills in Demand visa an international graduate needs to have an occupation on a skills list or be sponsored by their employer, with labour market testing and salary requirements.

The bill’s explanatory memorandum singles out (p. 60) VET Business Leadership and Management courses as examples of ‘low cost courses which are susceptible to use by non-genuine providers and students as a channel to work and extend their time in Australia’.

For this analysis, however, the EM relies on a 2023 parliamentary report, made before the March 2024 genuine student test, which reduced such pathways in general without needing to single out specific courses.

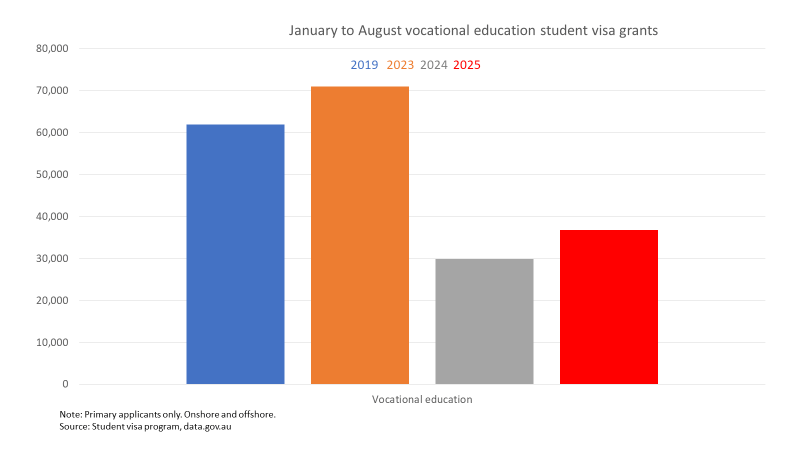

Combined with other student visa policies this has already significantly reduced the number of new student visas being issued for vocational education courses, as seen in the chart below.

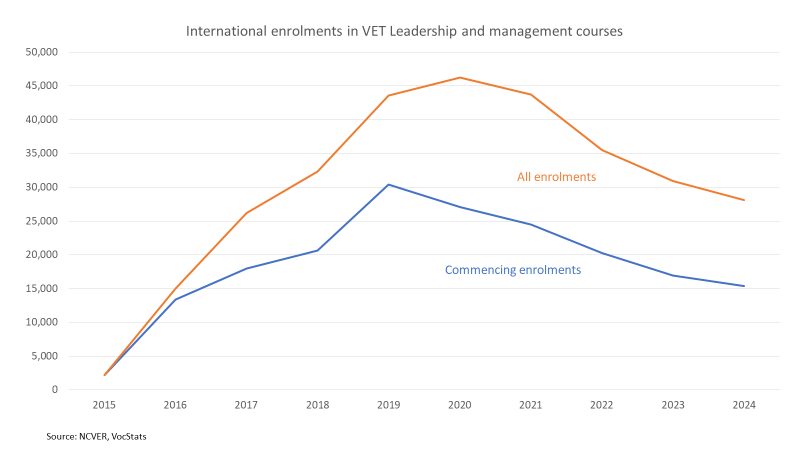

We can also see in the chart below that enrolments in VET leadership and management courses were already in significant decline before the March 2024 changes.

The public interest

If the minister cannot find convincing reasons to cancel a ‘class of courses’ on standard of delivery or skills grounds there is a broad ‘public interest’ provision: section 96B(1)(c).

The example given in the EM is ‘courses which are used by students to subvert immigration and education systems’ and ‘courses that are exploitative of their students’: p. 60

As noted earlier, there is already a power, held by the immigration minister, to suspend a provider with immigration issues: section 97. The amending provision would add the regulatory unit of a ‘class of course’ to the existing provider provisions. The rationale seems quite similar to the VET Business Leadership and Management course example, without pretending that Australia’s skills needs have any relevance.

If the migration system is being subverted surely this is a matter for the immigration minister? This bill does not even require the education minister to consult with the immigration minister before cancelling a class of courses on migration-related grounds.

If students are being exploited by the provider there is an existing provision for the ESOS agency to find that the provider is no longer ‘fit and proper to be registered’: section 7A. If this happens, the provider’s registration is automatically suspended: section 89.

The ‘public interest’ is a vague term that serves to lift restrictions on the minister’s power.

Kinds of providers

Cancelling a ‘class of courses’ punishes all providers offering the course when only some may have the problems – low quality, migration issues – triggering the cancellation. There is however scope for restricting suspensions and cancellations to a ‘kind of provider’: section 96B(4).

Despite the class of course being the regulatory unit, in deciding whether to cancel the minister can take into account whether the courses are taught by providers that have breached the ESOS Act 2000, the national code of practice for overseas students, or a condition of the provider’s registration: section 96B(2).

The bill pre-emptively excludes Table A (public) universities: sections 96C(1)(a), 96D(1)(a) & 96E(1)(a). The bill’s explanatory memorandum claims that they have lower integrity risks: p. 59. This is surprising given the minister doesn’t trust Table A universities to support their students, protect students and staff from gender-based violence, or to have proper governance systems.

The bill’s explanatory memorandum is not overly helpful on how the ‘kind of provider’ classifications might work. The example given of a possible exemption (p. 61) is ‘providers with unlimited self-accrediting authority’, but that would only add a few Table B (private) universities to the Table A institutions specifically mentioned in the bill.

Proxies for quality or integrity aside, it is hard to argue that graduates in the same field are surplus to Australia’s skills needs if from a non-Table A provider but within Australia’s skills needs if from a Table A provider.

Location

In deciding whether to cancel restrictions the minister can take into account the locations where providers are registered to offer courses: section 96B(2)(4).

It is not clear what inherent relevance location has to the cancellation decision. In the 2024 bill it had parallels with the proposed power to cap enrolments by location, on the idea that this would encourage international students to go to the regions.

Existing students

If the course has existing students its registration is suspended except for those students: section 96D. When they finish their course its registration is cancelled: section 96E.

If the course is still in its application phase the application is cancelled: section 96C (new since the 2024 version of the bill). If the course has no students its registration is cancelled: section 96E.

Parliamentary review

Cancellations are made by a legislative instrument. A legislative instrument must be tabled in the House of Representatives and the Senate and can be disallowed by either, unless the Act creating the instrument specifies otherwise. The ESOS amending bill exempts other legislative instruments from disallowance but not the cancellation provisions.

Update 28/11/2025: With the Senate amendment the minister must also table reasons for his decision.

Judicial review

The minister’s decision could be appealed on narrow grounds under the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977. These include errors of law, failures to observe the correct processes, no evidence to justify the decision, and improper exercise of power. The latter can include exercising a power for a purpose other than for which it was conferred, exercising discretionary power without regard to the merits of a particular case, exercising power in a way that is so unreasonable that no reasonable person could have so exercised it, and abuse of power.

Conclusion

I do not believe that the proposed course cancellation powers are justified or needed.

If there are course quality issues then ASQA or TEQSA should deal with them, using their specialist expertise and ensuring that if these problems exist then course or provider registration, as appropriate, is cancelled for both international and domestic students.

As most international students return home there is no good reason to force them to do courses related to Australia’s skills needs. The students who want to remain in Australia already have, via temporary and permanent visa rules, incentives to take courses reflecting Australia’s skills needs. Other reforms to migration law have made it more difficult to do courses for the purpose of prolonging time in Australia.

Relatedly, the immigration minister already has the power to suspend the registration of providers abusing the migration system.

Although exercise of the minister’s power to cancel classes of courses is not completely without checks and balances it has significant rule of law issues. It gives the minister broad discretion to personally decide what courses should not be offered, making the law hard to know. It does not apply the law equally, exempting Table A universities and unknown other groups of providers. It would punish all providers with some shared characteristic for the failings of some.

Rules specifically targeting clearly-defined wrongdoing are much better from a rule of law perspective. That’s generally what the ESOS Act 2000 as it stands does. The government has not given an adequate explanation as to why its existing powers are insufficient.