While I agree with the goals of today’s big migration policy changes, they will make life more difficult for universities relying on migration-motivated international students. In most cases, former international students will be able to stay in Australia on temporary graduate visas for less time than now. Other options for remaining in Australia, such as returning to a student visa, will become more difficult.

These policy changes aim to reduce temporary migrant numbers. The pressure temporary migrants place on accommodation and other services made this an urgent policy and political issue. But prior to this there were also significant concerns about temporary migrants themselves, in their vulnerability to labour market exploitation and prolonging their time in Australia in the often false hope of eventual permanent residence, as ‘permanently temporary’ migrants. The Parkinson migration review, released in March this year, set out an agenda for change.

Future policy on permanent residence is still under development, with some signals discussed below. Whether the number of former international students getting PR will go down remains to be seen. But clearer rules will mean PR aspirants can cut their losses at an earlier point. Fewer will delay important career and family events and decisions due to uncertainty about their long-term country of residence.

Shorter-stay temporary graduate visas

In September 2022 the government announced its decision to add two years to the sub-class 485 temporary graduate visa for graduates with degrees in areas of ‘verified skill shortages’. In the critique I wrote at the time I was ‘far from convinced that a 485 time extension is a good or ethical policy’, and so I am glad that this policy will be abolished.

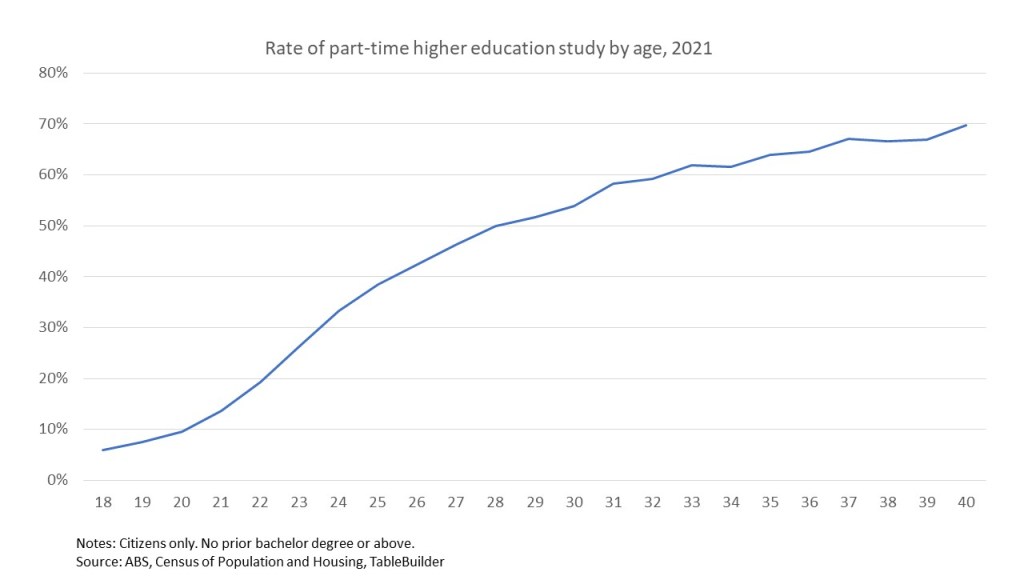

As the chart below from the migration plan shows, they will also cut the base time period for a masters by coursework from three years to two years, and for a PhD from four years to three years. The regional extension, however, will remain.

Read More »