As the latest OECD Education at a Glance publication confirms, Australia is a high tertiary education attainment country. But large-scale migration makes it hard to interpret Australian figures – what is the result of policies aimed at educating Australian citizens, and what is due to our commercial international education industry and skills-based migration program?

Although demand driven funding increased the annual number of people completing bachelor degrees, on my calculations using the ABS Education and Work survey additional citizen graduates of Australian universities account for slightly less than half of the increase in graduate numbers since 2013 — 406,000 additional Australian or New Zealand citizen graduates of Australian universities and 421,000 extra graduates who hold degrees from overseas universities or are non-citizen holders of Australian university degrees.

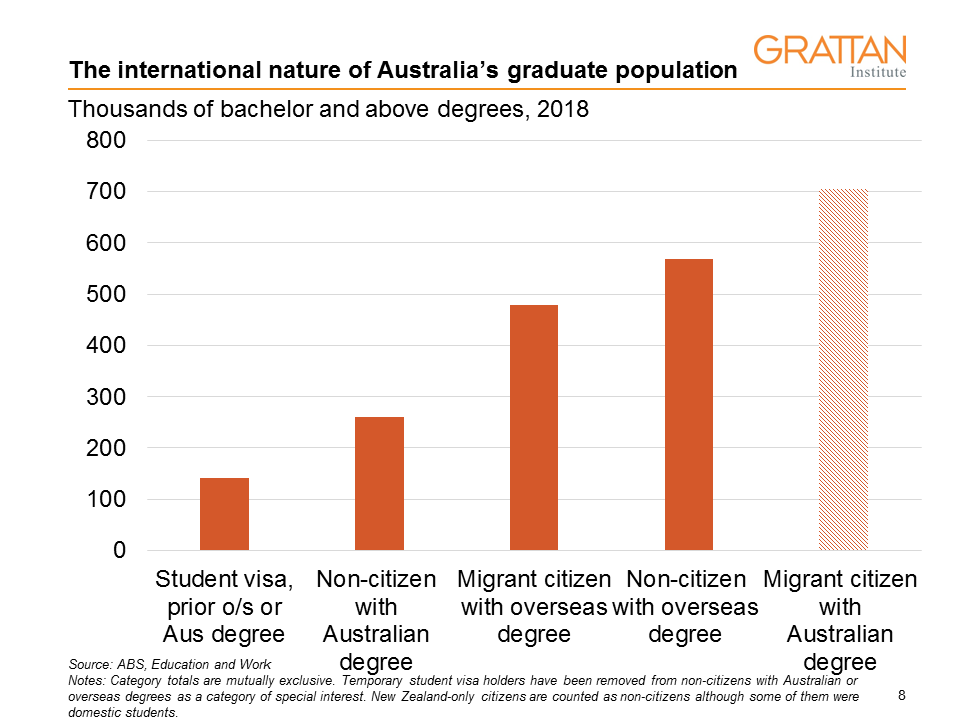

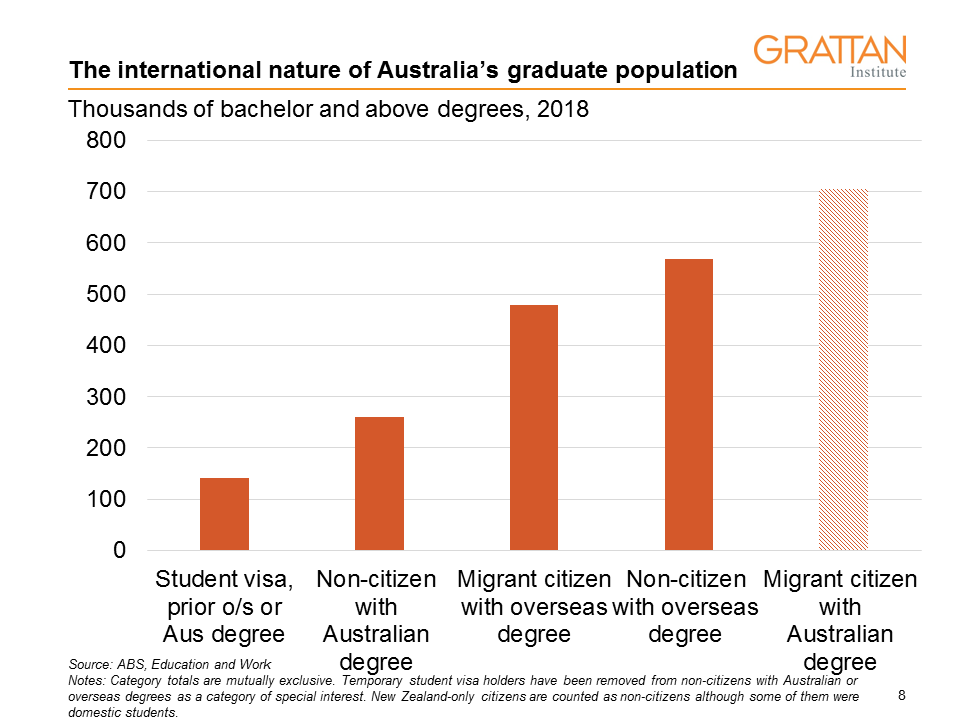

The chart below attempts to break the numbers down a bit further, although the categories are not straightforward.

Education and Work separately identifies people on a student visa, which it puts at 142,000 in 2018 (80 per cent with overseas degrees). I have deducted these from the other non-citizen categories. As postgraduate international enrolments have been growing more quickly than undergraduate in recent times, I expect this category to grow in future years.

In Education and Work, the ABS continues its irritating standard practice of not identifying permanent residents, who are entitled to a Commonwealth supported place and to remain indefinitely in Australia. There were 36,000 domestic students with PR in 2017. This means the ‘non-citizen with an Australian degree’ category is a mix of them (after they graduate) and former international students on temporary or permanent visas. With increasing numbers of completing international students getting 485 visas, I expect that this will be a growing category.

What I find most interesting in this data is the very large number of people with overseas degrees – more than a million in total. About 45 per cent have have taken out citizenship. Most of them would be the product of Australia’s skilled migration program, although there were also 58,000 New Zealand citizens, who can come to Australia without going through the usual visa system, with an overseas degree.

On right-hand side of the second chart I have a column ‘migrant citizen with an Australian degree’, representing just over 700,000 people, that in the first chart appears in the ‘domestic’ time series. Most of them, I think, would have been domestic students (just under half arrived in 1996 or earlier), but some largish proportion would have been people who arrived as international students and subsequently became citizens.

In 2018, 68 per cent of degree holders in Australia were Australian or New Zealand citizens with degrees from Australian universities. But because we cannot identify the former international students in this group, it is quite likely that more than a third of all degree holders in Australia acquired their qualification with no assistance from Australian higher education policy.