Yesterday the government introduced legislation to extend demand driven funding from regional and remote to all Indigenous students. Currently Indigenous students from major cities are funded from within each university’s capped maximum basic grant amount for higher education courses. If the legislation passes universities will get the full Commonwealth contribution value of all enrolled Indigenous students in demand driven funding eligible courses, with no funding cap.

What are current Indigenous enrolments by geographic category?

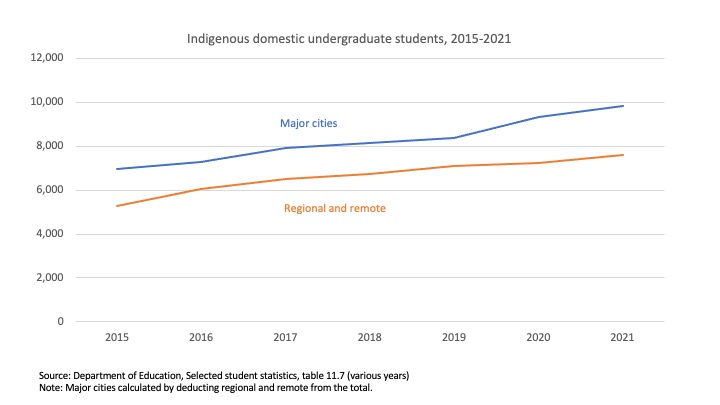

Demand driven funding only applies to bachelor degree students – of which more later – which makes it a funding category that is not also a publicly-reported statistics category. However a table in the annual equity statistics lets us calculate the number of undergraduate (ie bachelor + diploma + associate degree) Indigenous students by home geographic location. It shows that Indigenous students from the major cities outnumber regional and remote students. Enrolments from both groups have increased in recent years.

Participation and attainment rates

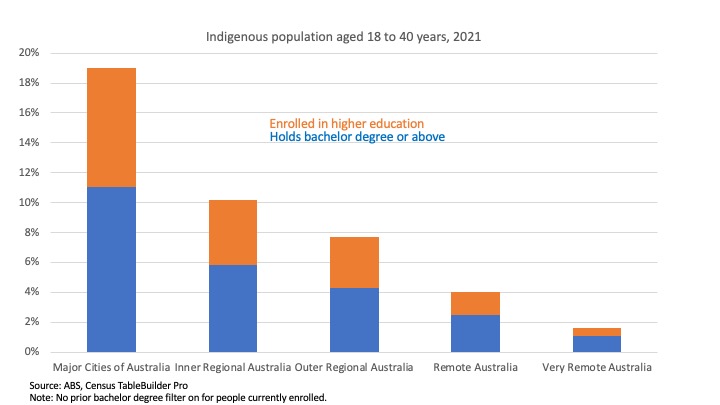

While only a minority of Indigenous Australians live in the major cities their participation and attainment rates are much higher (chart below) than those of Indigenous people in regional and remote areas. This explains why Indigenous students from major cities are a majority of enrolments in the chart above.

What is the pipeline of potential Indigenous students?

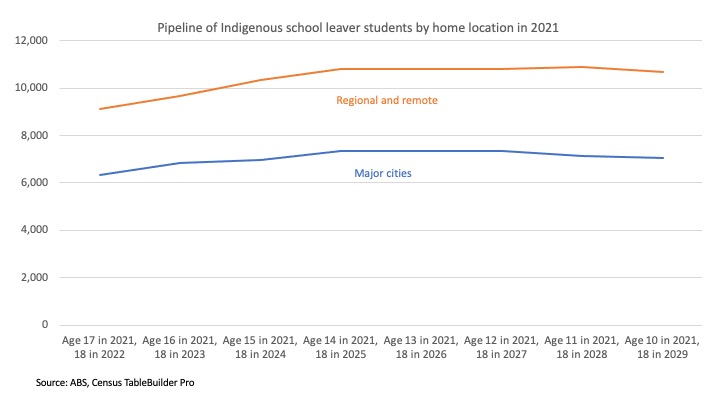

For school leaver students the current demographics suggest an increase in potential students through to the mid-2020s, but a plateau after that (chart below). Indigenous Year 12 completion rates are low and not improving, suggesting that demographic factors will be most important in lifting absolute numbers for this age group.

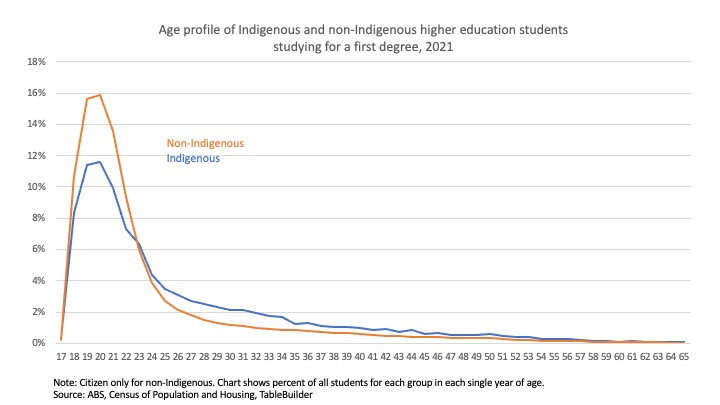

While both Indigenous and non-Indigenous enrolments skew towards early adulthood (chart below) a larger share of Indigenous students are older and therefore more likely to be admitted on some basis other than their school results.

A too-narrow demand driven funding model

One flaw in Indigenous demand driven funding is that it only applies to bachelor degree enrolments. That was not the original Bradley review intent when recommending demand-driven funding. Sub-bachelor courses were excluded at the last minute due to concerns about competition with vocational education and cost, and were instead put in a separate capped funding pool. This had perverse effects, encouraging universities to enrol students in bachelor degrees when they would have been better off starting in an enabling course or a diploma pathway course.

Indigenous students, probably reflecting their mature-age demographic profile, are particularly likely to use one of these pathways. They use enabling courses much more than non-Indigenous students (chart below). The Indigenous and non-Indigenous sub-bachelor enrolment shares for higher education entry courses are about the same in percentage terms, but this may understate the use of diplomas as pathways by Indigenous students, as the sub-bachelor category includes diplomas in foreign languages and music offered by sandstone universities as well as pathway programs.

For an unexplained reason this exclusion of sub-bachelor courses from the original demand driven funding system was continued when the regional and remote Indigenous demand driven scheme was announced in 2020 as part of Job-ready Graduates and began operation in 2021, and will if this week’s bill passes continue through to the all Indigenous students demand driven system.

Job-ready Graduates did, however, restore neutrality between bachelor and sub-bachelor courses, within a university’s overall maximum basic grant amount for higher education courses. This gives universities more scope to start students in diploma courses, with Indigenous diploma students funded out of the university’s Commonwealth Grant Scheme maximum basic grant amount.

While Job-ready Graduates improved funding arrangements for diploma courses it hit enabling courses hard. These are funded from each university’s grant for higher education courses but are free to the student. Universities receive a capped amount of a per-EFTSL enabling loading to partly compensate for lost student contribution revenue. Under Job-ready Graduates universities became more reliant on student contributions in some disciplines, but with no offsetting increase in the enabling loading. With the loading already less than the cheapest student contribution the financial viability of enabling programs was undermined. Enabling enrolments dropped 21 per cent between 2020 and 2021. Indigenous students were less affected, down 12 per cent.

Is the capped maximum basic grant amount much of an obstacle to Indigenous undergraduate enrolments?

Another issue is whether capped funding for undergraduate degrees is much of a constraint on Indigenous enrolments. Improving but still very high Indigenous attrition rates suggest that universities are, in their admissions practices, already operating at the edge of what is legal and ethical, given that many Indigenous students will end up with a HELP debt but not a degree. They do this to maximise higher education opportunities for Indigenous people.

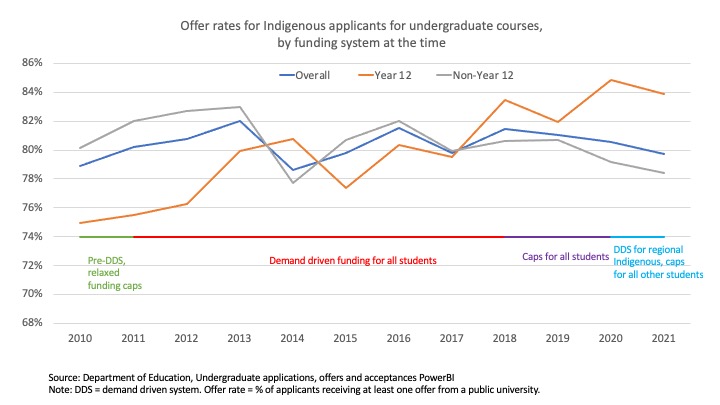

The chart below on offer rates for Indigenous applicants by funding system at the time shows, somewhat counter-intuitively, that overall offer rates seem a bit lower in demand driven funding periods, although the start of regional and remote Indigenous demand driven funding saw the Year 12 offer rate only slightly below its peak the year before. Total Indigenous applicants went up every year except 2018 between 2010 and 2021, with overall enrolments increasing despite fluctuations in offer rates.

The published data does not let me distinguish Indigenous commencing students by home location, but in the total enrolment figures in the first chart of this post the demand driven eligible Indigenous students grew by 4.9 per cent between 2020 and 2021, compared to 5.2 per cent for the major city Indigenous students who shared a funding pool with all other domestic coursework students. So again no strong evidence that demand driven funding for Indigenous students makes a significant difference to university decisions.

It is, however, worth noting that funding determinations for the regional and remote demand driven program suggest that universities expected more enrolments than eventuated, with estimated CGS revenue revised down. If so there was a willingness to supply but insufficient demand (the large differences between Commonwealth contribution rates in the JRG era make it possible that the numbers were there but the students chose courses with lower funding rates than anticipated).

The funding transition

So far as I know the government has not yet said how the transition to full Indigenous bachelor degree demand driven funding will work. There will be new funding agreements for 2024, by coincidence also the first year of the new policy. I think the most likely transition arrangement will be to calculate the most recent Commonwealth contribution value of major city Indigenous bachelor degree students for each university and deduct it from their maximum basic grant amount for higher education courses. This scenario is consistent with the modest estimated cost of $34 million over three financial years in the legislation’s explanatory memorandum – I assume this is the forecast Commonwealth contribution value of major city Indigenous students over and above those enrolled in the base year.

Conclusion

Overall I think the extension of Indigenous demand driven bachelor degree funding will not have much impact on Indigenous bachelor degree enrolments. Without it most universities would still have enrolled every Indigenous bachelor degree applicant they could within the law and their own admission requirements. They are all committed to Indigenous advancement.

Paradoxically the policy might help non-Indigenous bachelor degree course applicants more, by reducing zero-sum choices between them and Indigenous applicants.

For increasing Indigenous access to higher education spending the extra $34 million fixing the policy problems undermining enabling courses might have had more impact.

Possibly spending more money on primary and secondary education for such students might be more worthwhile too to increase engagement, retention and capability.

LikeLike

Yes, demand driven funding for urban Indigenous students will make a difference, but only if the right training and support are provided. I suggest the problem of funding bridging can be sidestepped, by building the needed training into the degree curriculum. This will help all students: urban, rural, indigenous, non-indigenous, domestic, and international. Professors will just have to accepted that some of the highly technical stuff, which hardly anyone uses, will have to be jettisoned to make room. 😉

LikeLike