The Universities Accord terms of reference asked the review panel to recommend higher education equity and attainment targets, and in their interim report they offer suggestions.

The general goal is equity group parity in higher education participation by 2035 (pp. 18, 20). There is some ambiguity about whether this applies for all equity groups. A few times only three of the main four – low SES, regional, and disability – are specifically mentioned for the 2035 target (pp. 9, 42, 43). For Indigenous students a target is referred to but not specified on p.43. The Indigenous contribution to the 2035 target is however, mentioned at pp. 40-41.*

Other potential equity groups such as first in family, care leavers, people from single parent families and children of asylum seekers may be added (p. 42)

The equity targets interact with an overall target of 55 per cent attainment by 2050. It is unclear whether this target is for people aged 25 to 34 years (pp. 9 & 36), employed persons (p. 33, distinguished from the 25 to 34 cohort), or all people/unspecified base (p. 22).

Whatever the exact 2050 target, it is well above current levels. Equity group parity is not just achieving the overall population participation and attainment rate now. It is chasing a rate that will, if other Accord policies work, be moving up.

This post discusses the practical obstacles to equity group targets that apply regardless of the precise targets set. It also questions whether a large increase in higher education participation would reliably be in the best interests of the additional students.

The academic pipeline

For parity in higher education participation and attainment to be achieved it requires an increase in the prior academic performance of the population generally and equity groups in particular.

A 55 per cent attainment target assumes that everyone with an ATAR of 45 or above should be at university. Currently that would not be achievable or in the best interests of many of those who do enrol. People who did not enjoy, or did not do well at, the more academic school subjects are less likely to want to go to university, and less likely to complete a course if they do. To repeat my mantra on this topic: a HELP debt without a degree is not ‘equity’.

ATAR is a relative rather than absolute measure so, for a 55 per cent attainment target to be academically feasible, the ATAR middle range would need to equate to higher absolute levels of academic performance than now.

Education minister Jason Clare recognises the academic pipeline problem. He hopes his early childhood and school policies will contribute to improvements. But does he expect radical change in the near term, a necessary condition of 2035 higher education participation parity? He undoubtedly wants to ‘close the education gap’, but also acknowledges that ‘big reform is hard and takes time, and not every great idea can be funded.’

We need to be clear on the scale of the challenge.

School results by measures of SES

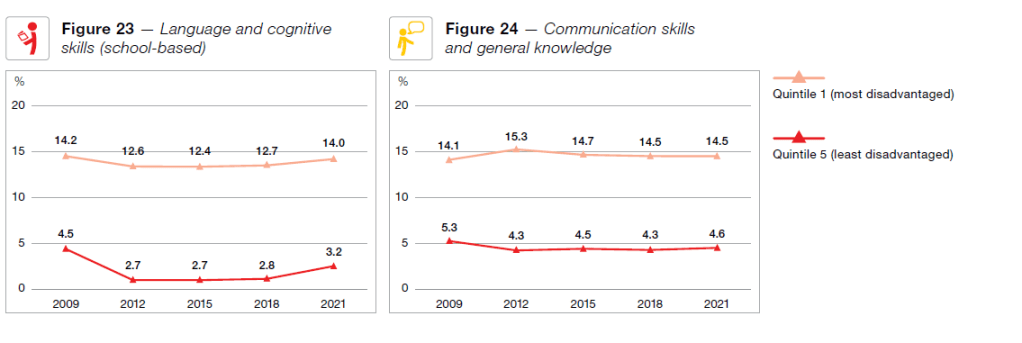

The Australian Early Development Census, of children in their first year of education, measures their development on five domains, covering physical health, social competence, emotional maturity, language and cognitive skills, and communication skills and general knowledge. Like higher education the AEDC uses an ABS SEIFA geographic proxy to measure social background, but the Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage rather than the Index of Education and Occupation.

Children from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to be ‘developmentally vulnerable’ in all the domains, but especially the more academic domains shown below from the 2021 AEDC. These are the children who will reach university age in the mid-2030s.

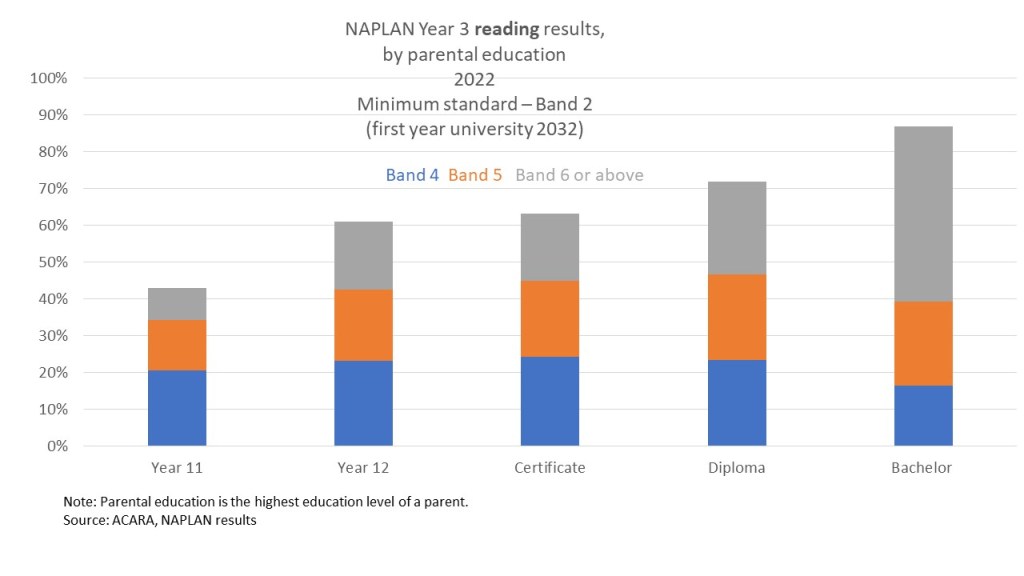

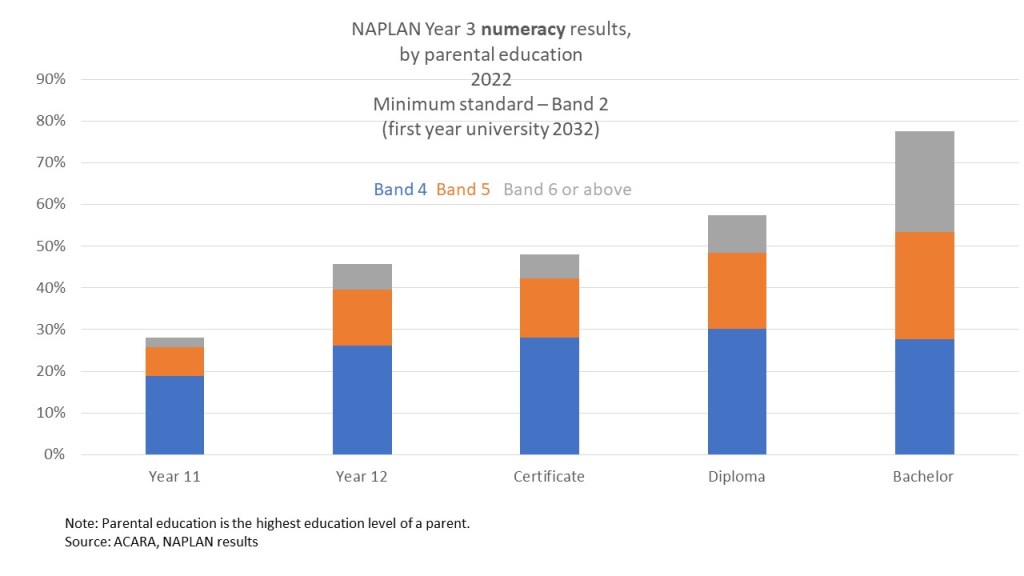

The Year 3 NAPLAN results, of students who will reach university age in the early 2030s, show the problem more clearly. There is a strong relationship between parental education and scoring well in reading and maths. Historically differences in performance persist as students move through their school years.

Can these result improve so much that parity in higher education participation is possible by 2035? The Accord interim report impliedly thinks that it is, but gives us no reason to believe that this is realistic.

Higher education risks

In setting its overall attainment target the interim report primarily takes the perspective of employers rather than students or potential students. But equity targets only make sense if the panel believes that higher education delivers benefits that members of ‘under-represented’ groups are missing out on.

While my support for demand driven funding reflects a belief that opportunities for higher education should be available, the student outcomes lessons of the last 15 years need to be reflected in policy and in the messages we send to young people.

While enrolling in a university degree can bring significant potential rewards it also has risks that have increased over time, despite some positive trends in recent years. As noted, this include students not finishing their course. Another important risk is graduating but not getting a job that delivers career or financial benefits that are better than vocational education or direct workforce entry.

Risks and rewards of different qualification levels

Achieving 55 per cent higher education attainment would require big changes in the course and career choices of young men. In the 25 to 34 years age range in 2022 they were more likely to have a Certificate III/IV or diploma (35.7 per cent) as their highest qualification than a bachelor degree or above (33.5 per cent).

Have these men made poor choices? Answering this question requires looking at their realistic options and outcomes.

Higher education application rates are already very high for people with ATARs of 70 or above. This means that most people taking vocational education courses had a lower ATAR or no ATAR. We immediately know from this that their course (and therefore career) and university options are more limited than high ATAR students.

In the labour market a wider range of attributes and skills are rewarded than in school or university. Market, industrial and political factors put floors and caps on income that also dilute links between the underlying traits affecting academic performance and income. But there is a link between ATAR and outcomes.

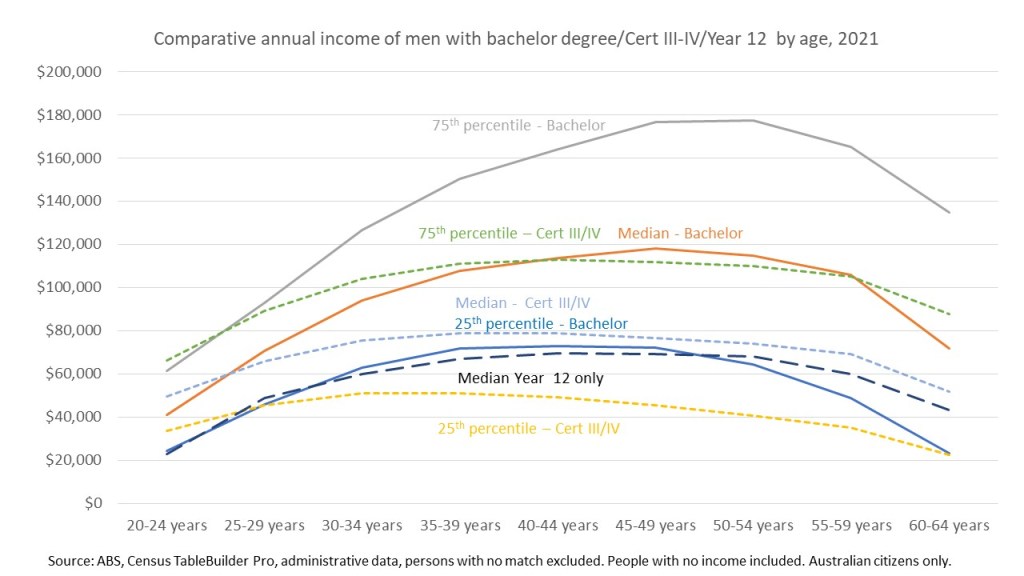

The average income associated with different qualification levels, therefore, is not the right metric for comparing options. We need to consider the range of possibilities.

The course and university options available for young men currently going into vocational education probably aren’t usually going to give them access to high graduate incomes, such as those at the 75th percentile and above in the chart below.

A bachelor degree leading to jobs that the graduate could have secured with Year 12 only – such as those at the 25th percentile in the chart below – has a similar earnings profile to someone who did finish their education at Year 12. As this latter person has no HELP debt and can start full-time work earlier they may, from a financial perspective, be better off overall.**

The median income for a man with a Cert III/IV qualification is above the 25th bachelor degree percentile, and also offers no HELP debt and an earlier career start.

Perhaps the men who could have gone to university, but instead chose a Cert III/IV related occupation, are among the more able of those workforces. If they are and reach the Cert III/IV earnings 75th percentile then they will, over a career, probably earn more than than the median male bachelor degree graduate. In middle age the bachelor degree median income is a bit higher than the Cert III/IV 75th percentile, but the latter group earns more in their 20s and 30s. From an income smoothing perspective those earlier higher incomes are a benefit.

From reaching Accord targets the relatively low male university attainment rate is a problem. But for the men themselves their educational choices look, on average, to be sensible decisions that maximise their income prospects.

For women the trade-offs are different. There is only a minor financial advantage at the median for holding a Cert III/IV qualification compared to completing formal education at Year 12. The 75th percentile of Cert III/IV earnings only exceeds median bachelor degree income in the 20-24 years age group, reflecting earlier career starts for people with vocational qualifications.

Women’s bias towards higher education (46.8 per cent higher ed/27.8 per cent Cert III/IV or diploma) looks, on average, to be based on sensible decisions that maximise their income prospects.

Not achieving targets

Equity group participation parity will not be achieved by 2035. Policies aimed at increasing school academic performance can produce improvements but not miracles. Most potential students won’t take advice that is contrary to their abilities, interests, and ambitions. They are the brake that can stop bad public policy doing too much damage.

But are the attainment and equity targets just harmless signals of where policy should head, with only the aspirations and not the precise numbers to be taken seriously?

Perhaps this is so, but I see downsides to targets. Young people already feel the weight of expectations to go to university from parents and others (this is a funny NZ send-up of parental attitudes to vocational education). Young people should be encouraged to make informed decisions in their own best interests, rather than ratcheting up the pressure to go to university.

But universities facing more aggressive and punitive regulation will surely try hard to meet their targets. We already see a lot of university marketing, much more than for vocational education (although Victorian TAFEs have had some good ad campaigns). ATAR-alternative admissions – with risk profiles that are rarely reported in a verifiable way – would increase.

Demand driven funding without targets remains the better policy option. It reduces constraints on educational decision making while respecting the decisions people make. The system can evolve as preferences and needs for different courses change over time.

Demand driven funding can’t eliminate over-education or skills shortages. People choose courses that interest them despite employment risks. The labour market can change more quickly than the education system. But demand driven funding can adapt as problems and opportunities become apparent, without pretending that, in 2023, we can accurately say what rates of higher education participation and attainment will be needed in 2035 or 2050.

*Reasons for not including Indigenous students in the 2035 target might be the wider gap to be closed and/or tensions between suggesting Indigenous higher education policy be ‘self-determined’ and the government setting a participation target.

**In the underlying income data data many 60+ bachelor degree men have nil income recorded, which requires further investigation.

More achievable, and useful, targets would be ones for post secondary education, including vocational education. There is no good reason why this should be limited to just universities. That would address the issue of those who do not want to be in an academic environment, or do not do well in it.

LikeLike

Agree with Tom that focus should be on post-secondary education. Your discussion seems to be informed by a presumption that direct workforce entry with no post-secondary education is a viable option for non-academic students. Is that true, and is it likely to remain so?

LikeLike