Gaby Ramia, a University of Sydney academic, has long written about international student issues, including their security and well-being. His latest book, International student policy in Australia: The welfare dimension, accuses successive governments of ‘policy inaction’ on international student welfare.

The book opens with what became an infamous statement by then Prime Minister Scott Morrison. When asked, in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, about the plight of JobKeeper-ineligible international students, Morrison responded that ‘these [student] visas and those who are in Australia under various visa arrangements, they’re obviously not held here compulsorily. If they’re not in a position to be able to support themselves, then there is the alternative for them to return to their home countries.’

A transactional relationship between Australia and international students

As Ramia’s book shows, in itself the prime minister’s statement was unsurprising. While Australia has longstanding consumer protection policies for international students, it has not offered general welfare-state type benefits. International students self-insure against the adversities that welfare states cover. As a visa condition they are supposed to arrive with savings. They are required to take out private health insurance. Education providers must provide information about welfare and other services, but are not obliged to deliver them.

Over the last quarter century the government has, to extents that vary over time, also encouraged international students to meet Australia’s labour market needs. But there was never any intention that the government fund international student related services. The government offered an Australian education and access to Australia’s labour market, not Australian welfare state support.

Ramia, by contrast, thinks that the government should take more responsibility for the welfare of international students. This should start with public transport concessions where these are not already offered and access to Medicare.

Ramia’s book was completed before the government changed its mind on international students, and started trying to cut their numbers. That policy turn creates new issues about the relationship between the government and international students.

Duties to foreign citizens

In areas of law regulating behaviour we typically don’t make distinctions based on citizenship status. Criminal, consumer and contract law are major examples. While migration law restricts work rights, once hired foreign nationals have the same protections under employment law as Australian citizens. For these laws to be effective they must apply to everyone.

But for welfare-state type services or payments it is less clear that Australia benefits from making them more widely available. These are a significant costs to taxpayers. As Ramia notes, even for citizens eligibility criteria excludes many from receiving them (although this is not the case for Medicare, a universal benefit for people with permanent residence or citizenship). Some international students have unmet needs, as Ramia’s book shows, but that does not of itself create an obligation for the Australian government to meet them.

In thinking about responsibilities, we need to consider why so many international students live in Australia. One reason is that countries in our region decided not to do what happened in Australia, the US or Europe and scale up their own publicly-funded higher education systems to meet demand. Instead their own private education sectors have taken larger enrolment shares than was the case in Australia, and many students chose to study overseas rather than take local options. Sometimes international students have home country scholarships, but most are privately funded.

If the countries in our region won’t support their higher education students, why should Australia?

Income tax

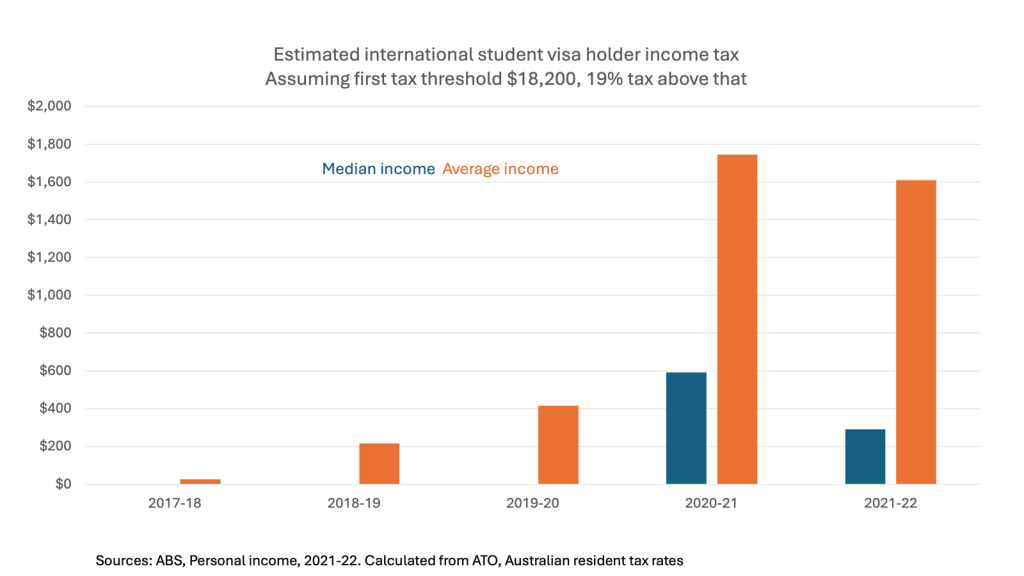

One of Ramia’s arguments for letting international students access Australia’s welfare state is that they pay income tax. While some do, most international students either don’t pay any or pay only small amounts of income tax.

Other than for exceptions during the COVID period, student visa conditions prohibit full-time work during semester. Significant numbers of international students don’t work for money and therefore don’t pay tax. The ABS survey results in the chart below show that, although work rates have increased since the 2010s, only about half of international students were employed as of each May in the 2021 to 2024 period. They are less likely to work than domestic students. However we can clearly see the employment dip in the first major COVID lockdown, to which I will return.

The ABS has in recent years published ATO-derived income data for international and other temporary visa holders. Estimating tax paid is not straightforward. A lower first income threshold can apply to people only in Australia for part of the year, which would increase tax paid compared to my chart below. On the other hand the figures are income, not taxable income (i.e. deductions can lower tax paid) and on my non-expert reading international students who were tax residents, defined as enrolled in a course that is 6 months or longer, would be entitled to the low-income tax offsets that applied during the period in the chart.

Assuming the standard $18,200 income threshold, below which no tax is paid, before 2020-21 the median income of international students was below that threshold, with modest amounts paid on average income. However, the increases in estimated tax paid in the chart were influenced by a COVID lifting of work hour limits. These were reimposed in mid-2023.

Migration and the welfare state in Australia

Australia’s welfare state has been built incrementally over more than a century, with eligibility rules varying over time and between programs. No law or document neatly summarises its key principles. But there is a common pattern of requiring a period of residence. In most welfare-state programs today eligibility depends on having at least the status of permanent resident, usually with a waiting period of 2-4 years.

The intuition behind these rules – if not the details in all cases – is I think sound. To build an entitlement to the insurance and income-smoothing benefits of the welfare state people pay into it over significant periods of time. For people born in Australia there is a long wait before they make any substantial financial contribution, but it is expected that they will do so as adults. The always-challenged finances of welfare states create pressure to minimise how many people take money out of the system but do not contribute.

For people on long-term temporary skilled visas this is a complicated area – for how long should they be expected to pay significant amounts of tax while getting little in return? (Although temporary migrants are exempt from paying the Medicare levy, which would presumably change for international students if they were eligible for Medicare.) But for students the argument can only start to work if we assume that most will remain in Australia and work full-time. Many initially do stay, but for 2010s arrivals rates of getting permanent residence and becoming long-term contributors to Australia tax revenue are low.

GST

While international students don’t usually pay much if any income tax, they do pay GST – a tax that goes to state governments (although collected by the federal government). It is state governments that would lose revenue with more generous public transport concessions to international students.

While all onshore international students would pay some GST, two big international student expenses, tuition fees and rent, are GST-exempt. Students can further save on GST by buying GST-exempt food.

State governments could argue, however, that this GST revenue helps cover the subsidies that all public transport users receive. Full-fare public transport users aren’t covering their costs; a concession fare just provides a larger subsidy. International students also benefit from other state-government spending for which it is impractical or undesirable to charge on an individual basis, including roads, parks, police and other forms of rule enforcement.

State governments might wonder, too, why they should indirectly subsidise the for-profit activities of education providers by making their cities more attractive to international students.

Unexpected emergency situations

If Scott Morrison’s statement in April 2020 reflected status quo policies I think are more-or-less right, why did I react to it negatively at the time and still think it was a mistake?

In a broad sense, I think it is because Australian policymakers haven’t fully thought through the consequences and implications of large-scale temporary but long-term migration. The COVID experience highlighted that sometimes Australia owes more than usual to temporary migrants.

COVID was an emergency situation that could not reasonably have been foreseen by students coming to Australia. As the employment chart above showed, many students lost employment during COVID lockdowns. While returning to their home countries was not necessarily a bad idea if the Australian alternative was a long lockdown – indeed in this respect international students were better off than Australian citizens, who needed permission to leave Australia – by radically altering what Australia offered students the government acquired a responsibility to provide some protection.

Although it never drew attention to its partial change of mind, the Morrison government in 2021 made holders of a ‘visa class permitted to work in Australia’ (which includes international students) eligible for a COVID-19 Disaster Payment Grant if they could not work for more than a week due to a lockdown. The entitlements were the same for citizens, permanent residents and temporary visa holders with work rights. The legal form was a discretionary grant rather than a legislated entitlement program, but it was a quiet acceptance of the problem. (I notice for more recent disasters assistance eligibilty is wider than permanent residence or citizenship, but would not include international students).

Keeping Australia’s side of a transactional relationship

I argued last month that policy on international education since 2022 has been too volatile – first unwisely opening the floodgates and then piling on counter-measures in desperate attempts to bring numbers back down again.

Issues arise when Australia encourages international students to choose Australia to receive some future benefit, but then withdraws that benefit before it can be taken up. In transactional relationships the parties don’t incur general obligations to each other, but each party needs to keep its side of the bargain. It is a matter of both ethics and ensuring that future incentives are credible.

The subclass 485 temporary graduate visa l discussed in last month’s post is a case in point. At short notice, the government lowered the maximum age for the visa from 50 years to 35 years, except for graduates with research degrees.

This policy was a recommendation of my former colleagues at the Grattan Institute, in their efforts to maximise the economic and fiscal benefits of migration. In itself their argument has merit. But I would argue that Australia should meet its commitment to students aged from their early 30s to late 40s who enrolled on the assumption that they were eligible for a 485 visa. I’m confident that some students did enrol on this assumption, as we can see big drops in student visa applications from the affected age groups. The rule change should have been grandfathered and only apply to new students.

Similarly, I think shortening the length of some 485 visas was reasonable in itself but should only apply to students granted visas after the policy change was announced.

Conclusion

While I do not agree with Gaby Ramia’s proposal to generally extend financial benefits to international students, he and others make valid points about the welfare of international students in Australia.

I don’t have fully developed ideas on what improvements could be made. But in this post I have outlined a couple of examples, payments in emergency situations and delivering on promised incentives, where I think Australian policy could improve without fundamentally changing the limited and transactional nature of the international student industry.

As an Australian citizen, when I became an international student at a university in another country, I understood this did not confer the rights of a citizen of that country. Similarly international students studying in Australia cannot expect to receive benefits which citizens receive. But in selling education, Australia needs to show it cares about its customers.

LikeLike

Interesting read and a valuable topic of discussion to Australia’s future.

Having access to healthcare, housing, dignity of labour are human rights and are not selective benefits. I believe these rights to be exclusive and guaranteed under the UNHRC which Australia is a signatory memeber. The public welfare state is guaranteed in effect to the public. If the government has decided to grant a visa to an individual to participate in the workforce be it through employment, education, refugee status, or otherwise, it has executed its authority and responsibility to safeguard the rights of the visaholder, to treat them equal under the law, and whose welfare is ultimately the responsibility of the government.

What can’t be defined by the statistics is qualitative study which represents a select group of temporary residents who are contributing to workforce, are paying high taxes, working overtime to save and survive, pay higher rent and interest on borrowings and countless other struggles still manage to move ahead. Work hard and save money. This is every migrants sob story but the reality is that it does not need to be.

The challenge to address in the policies should work to incentivise the above for creating a win-win situation and attracting the right people from overseas. In fact it is the failing of the system and policies that have led to certain groups and organisations gaming the system. And temporary residents often bear the brunt of such accusations. Eg: Housing crisis blamed on international students. As a result temporary residents rights are violated and policies changes have become severe, illogical and unethical with renegments made less that a year into the last change itself.

I agree that a more gradual and calculated approach to policy review and change is the need of the hour, where hasty changes have cost both Australian taxpayers as well as temporary migrants.

LikeLike