For many years I have published estimates of the domestic higher education participation rate at age 19. That age was chosen as it is the modal age of domestic higher education students.

To calculate a participation rate we need a count of domestic higher education students (Australian or NZ citizen, permanent resident) and a count of the ‘domestic’ population, that is all Australian or NZ citizens and permanent residents. There are significant issues with calculating both numbers – explained in this post from last year.

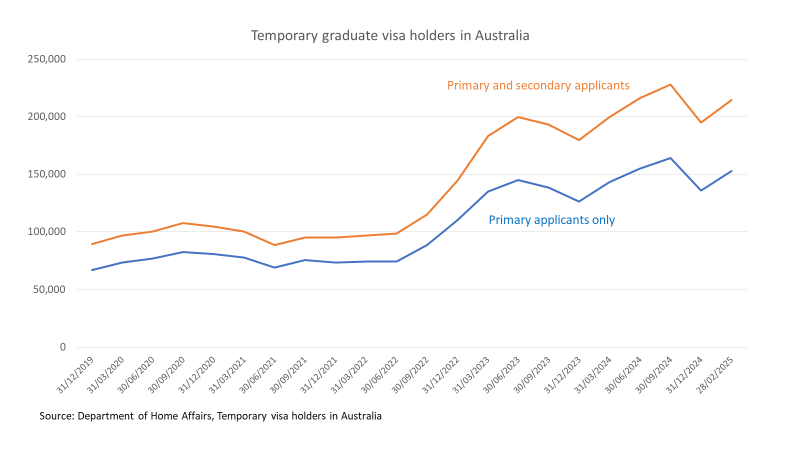

One of these issues is that the ABS population figures are inflated by temporary migrants. They need to be removed from the count to get a ‘domestic’ population figure. The ABS does not provide a temporary visa/domestic breakdown. As a workaround, my participation time series deducts international 19 year old higher education students from the ABS 19 year old population estimate.

A new methodology

This onshore higher education international students aged 19 correction, however, has several problems: a) the higher education enrolment data does not cover all higher education providers; b) vocational education students are not included; and c) other temporary visa holders in Australia are not included.

These omissions should lead to an under-estimate of the temporary visa population and, after their deduction, an over-estimate of the ‘domestic’ population.

To get a more accurate temporary population figure, I asked the Department of Home Affairs for data on 19 year old temporary visa holders in Australia on 30/06/2024, the date of the ABS population estimate. Some of these visa holders may not satisfy the population count rule – that the person is or will be in Australia for at least 12 months in a 16 month period. However, people with temporary visas who satisfy the 12/16 rule but who were temporarily absent from Australia on 30/06/2024 are omitted from the count.

Read More »